The Law Reform Commission is ... Law Reform Commission Act 1975. C

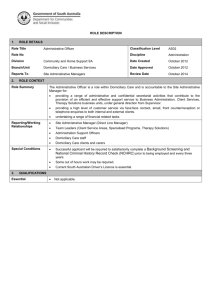

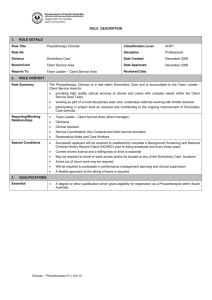

advertisement