CHINHUI JUHN University of Houston KEVIN

advertisement

CHINHUI

JUHN

Universityof Houston

KEVIN

M. MURPHY

Universityof Chicago

ROBERT

H. TOPEL

Universityof Chicago

CurrentUnemployment,

Historically Contemplated

our BrookingsPaper"WhyHas the NaturalRate of

UnemploymentIncreasedover Time?" analyzed long-termchanges in

joblessness among Americanmen.' We documentedthe dramaticrise

between 1967 and 1989 in both unemploymentand nonparticipationin

the laborforce amongprime-agedmales. Ourmainconclusionwas thata

steep and sustaineddecline in the demandfor low-skilled workershad

reducedthe returnsto workfor this group,leadingto high ratesof unemployment,laborforce withdrawal,andlong spells of joblessnessfor lessskilled men. We found that time spent out of the labor force and time

spentunemployedaccountedin roughlyequalmeasurefor the long-term

growthin joblessness.We concludedthatstructuralfactors,primarilythe

declinein the demandfor low-skilledlabor,haddramaticallychangedthe

prospectsfor a returnto low ratesof joblessnessany time soon.

After thatpaperwas published,things appearedto change.The 1990s

openedwith a brief recessionthatwas followed by the longest sustained

decline in unemploymentin modernU.S. history. By the end of that

expansion,the unemploymentratehad reachedits lowest level since the

late 1960s, falling below 4 percentfor the first time since 1969. Some

macroeconomistsarguedthatthe so-callednaturalrateof unemployment

ELEVEN YEARS AGO,

We thank the Brookings Panel participants for helpful comments. Earlier versions of

this paper were presented at the National Bureau of Economic Research Labor Studies

meeting and at the University of Missouri. We acknowledge financial support from the

Center for the Study of the Economy and the State and the Milken Foundation.

1. Juhn, Murphy, and Topel (1991).

79

80

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

had permanentlyshiftedto 5 percentor below.2Because we had emphasized changesin the structureof labordemandthathad made a returnto

low ratesof joblessnessunlikely,these facts presenteda challengeto our

1991 framework.Maybe we were just wrong-maybe the demandand

supplyframeworkof ourpreviousworkis inconsistentwith ratesof joblessness in the post-1990 period. If so, we would join a distinguished

groupof social scientistswho have drawnattentionto a significantempirical phenomenononly to watchthatphenomenondisappearimmediately

As it turnsout, however,the frameworkthatwe developedfor

thereafter.3

thinkingaboutpre-1990 patternsof joblessness also does fairly well in

jobless time in the post-1990period.

helpingto understand

In this paper we look in some detail at employmentdata from the

1990s, revisitingissues raisedin ourearlierwork.Specifically,we ask:

-Have the trendswe identifiedin ourearlierpaper-the concentration

of nonemploymentamongthe less skilled,the growthof nonparticipation

in the labor force, and the increased durationof joblessness-been

reversedwith the fall in aggregateunemployment?

-Did the expansionof the 1990s reallyreturnthe U.S. labormarketto

conditionsof the late 1960s, as unemploymentstatisticsseem to indicate?

-Does the economicframeworkof supplyand demandwe utilizeda

decadeago still help in understandinglong-termdevelopmentsin unemployment,nonemployment,andlaborforce participation?

Ouranswersare surprising.First,the basic trendstowardlongerspells

of joblessness and rising nonemploymenthave continuedin spite of the

prolongedexpansionof nationaloutputandthe concomitantfall in unemployment rates. Long jobless spells and labor force withdrawalwere

more importantin the 1990s thanever before. Second, the fall in unemploymentto levels close to historicallows is very misleading.Broader

2. See, for example, Stiglitz (1997), Gordon (1998), and Staiger, Stock, and Watson

(2001).

3. Malthus founded the club. His theory that the forces of endogenous population

growth doomed the common people to perpetual poverty "explained" why incomes had

failed to increase over the period his data covered. Publication of Malthus's theory was followed by two centuries of almost continuous progress. More recently, when the returns to a

college education were at a record low in 1979, Richard Freeman (1976) offered a supplybased theory in The Overeducated American, only to see returns to a college education

increase steadily over the next fifteen years, reaching a record high. To Freeman's credit,

his model did predict a rebound, although not so large and sustained as the one that actually

occurred.

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

81

measuresof joblessness show thatthe labormarketof the late 1990s was

morelike the relativelyslack labormarketof the late 1980s thanlike the

boominglabormarketof the late 1960s. Finally,the basic forces of supply and demand identified in our previous paper continue to have

explanatorypower.The theorydoes a reasonablygood job of explaining

those trendsthathave continued,as well as those thathave changed.

Recentdataalso provideconsiderableinsightinto what has happened

in the labormarketover the past decade.Overthe 1990s, even as unemploymentwas falling,time spentout of the laborforce was rising.In fact,

the increasein time spent out of the labor force was so large that total

joblessness-which combinesthe unemployedwith those who have withdrawnfrom the labor force-was as high at the business-cyclepeak in

2000 as it hadbeen at the previouscyclical peakof 1989, even thoughthe

unemploymentrate was roughly2 percentagepoints lower. In terms of

totaljoblessness, the often-praisedboom of the 1990s really represented

little in the way of employmentprogressfor Americanmales.

Althoughthe growthin the amountof time Americanmales spendout

of the labor force continuesa trendfound in our earlierresearch,other

featuresof the datachangedin the 1990s. The real wages of less-skilled

men, which had been falling steadilysince the early 1970s, stabilizedin

the 1990s andeven reboundedslightlyin the secondhalf of the decade.It

appearsthatthe thirty-yeartrendtowardgreaterwage inequalityhas run

its course,at least at the bottomof the wage distribution.The dataon joblessness reflect the impact of the changingwage trends.The long-term

divergencein employmentrates between low-wage workersand those

with higherwages, so pronouncedin our earlierwork, has stopped,and

unemploymentand wage gaps across skill groups have narrowed.The

congruencebetween patternsof change in wages and in employment

comportswith our previous work, which stresseddemand-drivenwage

changes as the dominantfactor driving secularchanges in employment

rates.

We are not the first to study the decline in unemploymentin the

1990s. Othershave emphasizedchangesin the compositionof the labor

force as a source of this decline. RobertShimerfound that aging of the

laborforce is importantin explainingthe decline in unemployment,particularly compared with the late 1970s.4 Lawrence Katz and Alan

4. Shimer (1998).

82

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

Kruegerinvestigatedto what extent the withdrawalof the incarcerated

populationfromthe laborforce, amongotherfactors,has led to a dropin

the aggregateunemploymentrate.'Otherpapershave exploredthe role of

improvementsin job searchtechnology.Forexample,DavidAutorargues

that temporaryhelp agencies may have helped improve the efficiency

with whichjob seekersarematchedwithemployers,thusbringingabouta

The arrivalof the Internetmay have

declinein frictionalunemployment.6

also reducedsearchcosts, althoughits impactis less certain.7

We show in this paperthata sharpdecline in the incidenceof jobless

spells accountsfor the lowerunemploymentratesof the 1990s,butthatat

the same time durationsof spells have remainedhigh. This fact is inconsistentwith a theorybuilt on decliningsearchcosts, which would imply

shorterunemploymentspells.

A relatedline of researchcomparesthe divergencein employmentoutcomes betweenthe UnitedStatesandEurope.Althoughboththe U.S. and

the EU economies may have experienced similar patterns of labor

demandduringthe 1970s and the 1980s, it is widely believed thatmoreflexiblelabormarketsandwages keptAmericanunemploymentratesrelatively low, while Europeanratesrose. Along these lines, severalpapers

emphasizethe importanceof interactionsbetweenmacroeconomicshocks

and labor marketinstitutions.8These papers find that althoughneither

macroeconomicvariables(oil prices, real interestrates,total factorproductivity,the laborshareof income)norlabormarketinstitutionvariables

(unemploymentbenefitsandduration,unioncoverage,collectivebargaining, employmentprotectionpolicies) alone can explain the differences

betweenthe UnitedStatesandEurope,a modelthatallows for interaction

effects fits the data well. But this shocks-plus-institutions

frameworkis

less successful in understandingrecentchanges in U.S. unemployment.

For example, Giuseppe Bertola, FrancineBlau, and Lawrence Kahn

5. Katz and Krueger (1999). They conclude that up to 0.4 percentage point of the rise in

the male employment-to-population ratio from 1985 to 1998 could be due to the bias from

ignoring the institutionalized population. For the sample of prime-aged males we study

here, the bias could be larger, further underscoring our finding that labor market conditions

did not improve much for prime-aged males in the 1990s.

6. Autor (2000a).

7. Autor (2000b); Kuhn and Skuterud (2000).

8. Bertola and Inchino (1995); Blanchard and Wolfers (2000); Ljungqvist and Sargent

(1998); Bertola, Blau, and Kahn (2001).

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

83

reportedthat the model significantlyunderpredictsthe decline in U.S.

unemploymentin the late 1990s.9

We revisit the evolution of joblessness in the United States, using

thirty-fouryears (1967-2000) of microdatafrom the CurrentPopulation

Surveys(CPS) conductedby the Bureauof the Censusandthe Bureauof

LaborStatistics.Ourmainconclusionsarethe following:

-Falling unemploymentrates over the 1990s greatlyexaggeratethe

improvementin labormarketconditionsfor prime-agedmales. Rates of

overalljoblessness-which includetime out of the laborforce-remained

roughlythe samein the late 1990s as they hadbeen in the late 1980s,even

as unemploymentrates fell. Rising labor force nonparticipationamong

prime-aged men largely offset declining unemployment,so that the

employment-to-population

ratioheld constant.

-Trends towardlongerdurationsof both unemploymentand nonemployment continuedin the 1990s, in spite of declining unemployment

rates.The probabilityof enteringunemployment(or nonemployment)fell

dramaticallyduringthe 1990s. The decline in the incidence of jobless

spells was so large that the likelihood of experiencingone reachedits

lowest level in the thirty-fouryearscoveredby ourdata.But therewas no

decline in the duration of unemploymentspells-these were about

2.8 weeks longerin 1999-2000 thanthey hadbeen a decadeearlier-and

the durationof nonemploymentspells increasedby over fourmonthsduring the 1990s. Broadlyspeaking,all of the long-termgrowthin joblessness is the productof longerdurationsof jobless spells.

-Although nonemploymentcontinuesto be concentratedamonglessskilled men, the trendtowardrisingjoblessness among the least skilled

reversedcourse somewhatin the 1990s. The largest declines in unemploymentoccurredamongmen in the lowest skill categories.Unemploymentamongmen in the bottom10 percentof the wage distributionfell by

4.6 percentage points between the cyclical peaks of 1989-90 and

1999-2000, while the declinein unemploymentat the medianof the wage

distributionwas about 1 percentagepoint. In contrast,over the longer

term the growth in nonemploymentis heavily weighted toward lessskilled men. Among men at the bottomof the wage distribution,the nonemploymentrate increasedby 13.5 percentagepoints between the late

9. Bertola, Blau, and Kahn (2001).

84

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

1960s and 2000, but by less than 1 percentagepoint for men with wages

abovethe medianof the distribution.

-The long-termdeclinein the real wages of less-skilledmen stopped

in the early 1990s and actuallyreverseditself slightlyin the latterpartof

the decade.Althoughthe wages of highly skilled men grew most rapidly

of all duringthe 1990s-continuing past patternsof relative growthinequalitybetweenmen at the bottomof the wage distributionandmen at

the mediancontractedslightlyover the decade.Overall,the trendtoward

greaterwage inequalityappearsto have stoppedfor males in the bottom

half of the wage distribution.

-Joblessness among less-skilled men has shown up increasinglyas

time spent out of the laborforce ratherthan as time spent unemployed.

Consistentwith our earlier work, we believe that this continuedtrend

towardlaborforce withdrawalreflectstwo factors:relativelylow returns

to work(realwages for the least skilledremainsubstantiallylowerthanin

the past) and increasinglyattractivenonworkopportunities,such as collecting disabilitypayments,which have shifted labor supply among the

least skilled.We findthatmorethan40 percentof the growthin nonparticipationis associated with an increase in men claiming to be ill or

disabled.

-Despite rising wages and rates of labor force participationfor

women,the highrateof joblessnessamongless-skilledmenis not the outcome of improvedlabor marketopportunitiesfor their workingwives.

Nonemploymentratesandratesof laborforce withdrawalincreasedmost

amongmen who did not have a workingwife. Looking acrossthe male

wage distribution,the proportionof men with a workingwife actuallyfell

amonglow-skilledmen, whose wages andemploymentrateswerefalling,

androse amongmen in the top 40 percentof the wage distribution,where

wages rose and employmentrates were stable. We conclude that longtermchangesin joblessnesshave been the resultof adverseshifts in labor

demand, perhaps coupled with policy-driven shifts in labor supply,

amonglow-skilledmen.

Data

Our data are drawnfrom the 1968-2001 AnnualDemographicFiles

that supplementthe MarchCPS. The CPS collects informationmonthly

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

85

from a rotating,randomsample of approximately50,000 U.S. households. It forms the basis for publishedgovernmentstatisticson earnings,

employment,unemployment,and laborforce participation,amongother

measures.Whereaspublishedlabor marketstatistics rely on questions

abouteach surveyrespondent'semploymentstatusin the referenceweek

of the survey(usuallythe thirdweek of the month),we studyretrospective information,collected each March,on labormarketoutcomesin the

previous calendaryear. Hence our data cover the thirty-fourcalendar

yearsfrom 1967 through2000.

In additionto personaland householdcharacteristicsfor each respondent, the retrospectivedata in the March survey recordthe numberof

weeks duringthe previousyear that the respondentworked,was unemployed, andwas out of the laborforce, as well as the respondent'snumber

of unemploymentspells. We measuretime spentunemployed(U) as the

percentageof the year spentin thatstate(for example,for the ith individual, Uiis the numberof weeks unemployeddividedby 52); time spentout

of the laborforce (0) andtime spentnonemployed(N = U + 0) aremeasuredin analogousfashion.This differsfromthe usualmethodof measuring time in unemployment,whichdividesweeks unemployedby weeks in

the labor force. Our method better summarizesthe allocation of time

across the three states, and it naturallyaggregatesacross individuals.'0

Using methodsdescribedbelow, we use informationon weeks worked,

unemployed,andout of the laborforce to calculateboththe incidenceand

the durationof jobless spells.

The survey also records a respondent'sannual earnings and usual

weekly hours workedfrom all jobs as well as occupation,industry,and

othercharacteristicsfor the longestjob held duringthe previousyear.We

use the informationon earnings,weeks worked,andhoursworkedto calculate averagehourlywages and to assign individualsa percentileposition in the overallwage distribution,as describedbelow. This allows us to

trackchangesin employmentoutcomes(U, 0, andN) for personsin differentpartsof the wage distribution.

We focus ouranalysison malesbecausethey were the focus of ourearlier work and because labor force participationissues for women are

significantlymore complex. To avoid issues associatedwith early retire10. Since the denominator for Ui, Ni, and Oi is always 52, the corresponding jobless

rate is simply the sample average of weeks in the state divided by 52.

86

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

ment, Social Security,and pensions,we focus on men who have one to

thirtyyears of potentiallabormarketexperience.For high school graduates this cutoffyields men who areroughlynineteento forty-nineyearsof

age, with correspondinglyhigher age intervals for those with more

schooling.We defineyears of labormarketexperienceas the smallerof

two numbers:age minusyears of educationminus seven, and age minus

seventeen."In addition,in orderto avoidmeasurementproblemsfor men

who spentpartof the year in school or in the military,we exclude those

who reportthat they did not work partof the year because of school or

militaryservice.

The employmentmeasureswe study are based on CPS respondents'

weeks worked, weeks unemployed,weeks out of the labor force, and

numberof unemploymentspells duringthe previousyear, as reportedin

the surveyweek. Using these data,we are able to identifythe fractionof

respondentswho experiencedsome unemploymentor time out of the

laborforce duringthe year, as well as the numberwho workedno weeks

duringthe year.We referto the latterevent as full-yearnonemployment.

Imputing Wagesfor Nonparticipants and Other Adjustments

We constructtwo samplesfor analysis. The "wage sample"contains

non-self-employedmen for whom valid observationsare available on

annualearnings,weeks worked,andusualweekly hours.'2Formen in the

wage sample,we calculatean hourlywage as the ratioof annualearnings

to the productof weeks workedand usual weekly hours.The "employment sample"includesthe entirewage sampleplus those men who lack

valid wage databecausethey did not work.For men not includedin the

wage sample,we imputea statisticaldistributionof wages basedon education,experience,andweeks worked.Foreach individualwith recorded

earnings,weeks, and hourswe projectthe log hourlywage on a quartic

function in potentialexperience,and we assign each individuala per11. We use age minus education minus seven rather the standard measure, age minus

education minus six, because age is measured at the survey week and we wish to measure

potential experience at the time of our wage and employment measures (which is the year

before the survey).

12. For the early years (before the 1976 survey) we impute usual weekly hours from

hours worked in the last week and individual characteristics, and we impute weeks worked

and unemployed from the categorical data based on averages calculated for the 1976-80

period.

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

87

centile rankbased on his positionin the distributionof the residuals.For

personswith zero weeks workedin the previouscalendaryear,we impute

a wage distributionbasedon the observeddistributionof wages for those

who workedfrom one to thirteenweeks in that year.'3The imputation

assigns ten probabilityweights-each correspondingto the probability

that the individual'swage would come from a given decile of the wage

distribution-along with a meanwage for each decile.

Our 1991 papersoughtto explainchangesin jobless time by changes

in wages across skill categories. As we showed then, the relationship

betweencalculatedwages andtime workedduringa yearis contaminated

by measurementerrorin the latter,andthe relativeimportanceof this type

of measurementerrordeclines with the numberof weeks workedin the

previouscalendaryear.'4This builds in a negative relationshipbetween

labor supply (weeks worked)and calculatedwages, particularlyamong

men with high calculatedwages. As in our 1991 paper,we use data on

hourlywages for Marchrespondentswho were also in the outgoingrotation groupsto calculatethe wage adjustmentsthat would equatethe distributionsof calculatedretrospectivewages from the previous calendar

year and reportedhourly wages from the survey week. We then apply

these adjustmentsto each percentileof the wage distribution.The procedure effectively compresses the wage distributionin each year by an

amountthatwe attributeto measurementerrorin calculatedwages.

Armed with calculatedwages for those in the wage sample and an

imputedwage distributionfor those withoutvalid wage data, we group

individualsinto five "skill"categoriesbasedon theirpositionsin the wage

distribution.The percentileintervalsare 1-10, 11-20, 21-40, 41-60, and

61-100. As describedabove, each individual'swage percentileis calculatedbasedon his wages relativeto those of men with the samelevel of

experiencein a given year.Individualsin the wage sampleareassignedto

one of the five categoriesbased on theiractualwage, whereasthose with

13. Men with zero weeks worked resemble those with one to thirteen weeks worked in

terms of years of schooling completed and in terms of living arrangements (living alone,

with a spouse, or with other family). We also matched the outgoing rotation groups to the

March survey, yielding data on current (March) hourly wages for those who worked during

the survey week. Among individuals with zero weeks worked in the previous year but who

worked in the survey week, average log wages are nearly identical to those of men who

worked one to thirteen weeks in the previous year. See Juhn, Murphy, and Topel (1991) for

further details.

14. See Juhn (1992) for a more complete description.

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

88

imputed wages are assigned probabilities of being in each of the

categories.

Changes in Wages, 1967-2000

In light of the prominencewe assigned to wage changes in our 1991

paper,it is worthwhileto review what has happenedto both wage levels

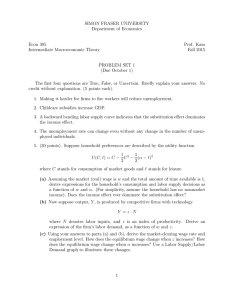

and the distributionof wages since then. Figure 1 and table 1 summarize

the mainfeaturesof the data.Figure 1 shows trendsin real hourlywages

by wage percentilegroup(skill category)since 1967;the dataareindexed

to equal 100 in 1970. Forourpurposesthe most interestingaspectof these

datais thatwage inequalitystoppedincreasingin the 1990s, especiallyat

the lower end of the wage distribution,andthatthe real wages of all skill

categories increased after 1993. For less-skilled workers, real wage

growthin the 1990s representeda slight reversalof a twenty-yeardecline

in the returnsto work,whichhadfallenby nearly30 log pointsafter1972.

Figure 1. Real Wages, by Wage Percentile Group, 1967-2000a

Index,1970= 100

115 110

to 1

1050 -61

100

-

'

-

''''"

95

90

85

I to 40

80

75

II to20

to

I

1970

I

I

1975

1980

~ ~

~~~~~~~~I

1985

1990

1995

Source: Authors' calculationsbased on annualMarchCurrentPopulationSurvey (CPS) data.

a. Reportedhourly wage (in naturallogarithms)is projectedon a quarticfunction in potentialexperience. Men are assigned a

percentile category based on their position in the residual distribution.Wages for nonworkersand self-employed workers are

imputed.

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

89

Table 1. Changes in Real Wages, by Wage Percentile Group, 1967-2000a

Percent

Wagepercentilegroup

Period

Ito10

11to20

21 to 40

41 to 60

61 to 100

1967-69 to 1988-89

1988-89 to 1994-95

1994-95 to 1999-2000

-24.8

-3.9

6.1

-19.9

-7.1

6.7

-12.7

-8.3

6.8

-4.0

-7.6

6.4

5.5

-3.6

10.7

1988-89 to 1999-2000

1967-69 to 1999-2000

2.2

-18.7

-0.4

-13.2

-1.5

-5.9

-1.2

2.4

7.1

16.2

Source: Authors' calculations using annualMarchCurrentPopulationSurvey (CPS) data.

a. Reportedhourly wage (in naturallogarithms)is projectedon a quarticfunction in potentialexperience. Men are assigned a

percentile category based on their position in the residual distribution.Wages for nonworkersand self-employed workers are

imputed.

Even so, average wages of the least-skilled men were roughly 20 percent

lower in 2000 than in the late 1960s (table 1), whereas those of men in the

top 40 percent of the distribution increased by a roughly equivalent

amount. As we showed in our 1991 Brookings Paper, wage declines were

most prominent among those whose employment outcomes are most sensitive to wage changes-the least skilled-whereas rising wages are concentrated among those with less elastic labor supply.

With this evidence as background, we turn to evidence on changes in

joblessness, both in the aggregate and across the wage percentile groups

defined above. We return to the implications of wage changes in the concluding section.

Unemployment, Nonparticipation, and Nonemployment

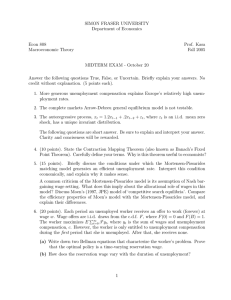

We begin by describing trends in unemployment and comparing our

March CPS-based data with unemployment statistics from the monthly

CPS published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Figure 2 shows that by

2000 the unemployment rate had reached its lowest level in thirty years,

and unemployment rates in 1999-2000 were close to the extremely low

rates seen during the late 1960s.15This is the culmination of a long downward trend in unemployment: in both the 1991-92 and the 2001-02 recessions (not shown), the peak unemployment rate was lower than the peak

in the preceding recession, reversing a trend of rising peaks across the

15. The publishedratehas been adjusteddownwardby 0.86 percentagepointto equate

the meansof the monthlyandthe Marchseriesover the sample.

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

90

Figure 2. AlternativeMeasuresof the UnemploymentRate, 1967-2000

Percent

10

Monthlysurveyb

Marc surve'

9

8

1111

7

6

5I-

March ~ surveyvr

h~smpe Mrc

4/

3

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

Source: Authors'calculationsbased on Bureauof LaborStatisticsand MarchCPS data.

a. Subsetincludingonly prime-agemales; calculatedas the numberof weeks unemployeddivided by 52.

b. Each observationfrom the monthly survey is reducedby 0.86 percentagepoint to equate the means of the monthly and the

Marchsurveys over the sample.

It appearsfrom the figure

1970-71, 1974-75, and 1982-83 recessions.m16

thatthe U.S. economyhas come full circle:unemploymentrose for fifteen

years (from 1968 to 1983) and then fell over the next seventeenyears

(from 1983 to 2000), with interveningcyclical swings. One might conclude from these data that the labormarketconditionsof the late 1960s

andlate 1990s were comparable.

Figure 2 also shows annualunemploymentrates for our sample of

prime-agedmales (calculatedfrom the MarchCPS dataas weeks unemployed divided by weeks in the labor force). Although the two series

shouldnot be identicalbecauseof differencesin the underlyingpopulations (oursampleconsists only of prime-agedmales, whereasthe overall

unemploymentdata are from the full populationof labor force participants aged sixteen and over), the two series are remarkablysimilarin

terms of underlyingtrendsand rankingsof cyclical variationsin unem16. The recession of 1980 did not fit this pattern, but as the figure shows, it did not represent much of a peak in terms of unemployment rates.

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

91

ployment.One would reachthe same basic conclusionsaboutunemployment trendsfrom the publishedmonthlyseries as from our calculations

based on the MarchCPS data.Fromhere forwardwe analyzethe March

CPS dataexclusively.

A majorfinding of our 1991 paperwas that the long-termgrowthin

unemploymentgreatlyunderstatedthe growthin joblessness.Recentdata

suggest thatchangesin unemploymentshown in the aggregateand in the

CPS statisticsare even more misleadingfor the 1990s. This is illustrated

in figure 3, which plots two series: the fractionof annualweeks spent

unemployedandthe fractionof annualweeks spentout of the laborforce.

The nonemploymentrate is the sum of these fractions,so that the combined height of the two shadedregions representsthe proportionof the

year spent out of work. Figure 3 confirmsthat measuredunemployment

fell duringthe 1990s to levels comparableto those in the 1960s, but the

conclusion in terms of overall jobless time is much different:the late

1990s were much like the 1980s, in that the decline in unemployment

Figure 3. Unemployment,Nonparticipation,and Nonemployment,1967-2000

Percentof calendaryeara

16 -

Nonemploymentb

1412 10 -

4

1970

1975

1980

Source: Authors' calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

a. Numberof weeks a year in indicatedstate divided by 52.

b. Unemploymentplus nonparticipation.

1985

1990

1995

92

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

over the 1990s is not reflectedin a lower overallrateof joblessness.This

means that, on net, men who left unemploymentdid not find jobs but

ratherleft the laborforce, so thatthe employment-to-population

ratiowas

unchangedfromits level in the 1980s.

Table 2 summarizesthe data in figure 3 by aggregatingthe data into

nine time intervalscorrespondingroughly to peaks and troughsin the

business cycle, as measuredby aggregateunemploymentrates. Unemploymentshows a strongcyclical patternas well as a long-runupward

trend(whethermeasuredpeakto peakor troughto trough)untilthe recession of 1982-83. After 1982-83 unemploymentratesfall or stay constant

(again whethermeasuredpeak to peak or troughto trough).In contrast,

the fractionof the year spent out of the laborforce rises betweenevery

pairof intervals.In fact, whereasthe unemploymentratein 1999-2000 is

very close to its level in 1967-69, the nonemploymentrateis 4.7 percentage pointshigher,andthe fractionof the year spentout of the laborforce

is roughlydoublewhatit was in 1967-69. It is difficultto concludefrom

these datathatemploymentconditionsof the late 1960s andthe late 1990s

were "similar"in any meaningfulsense.

Consider next the eleven-year interval between the business-cycle

peaks of 1988-89 and 1999-2000. Over this peak-to-peaktime spanthe

unemploymentratefell by 1.3 percentagepoints-from 4.3 percentto 3.0

percent-but the percentageof men who were out of the laborforce rose

by exactly the same amount,from 6.7 percentto 8 percent.This left the

nonemploymentrateat the same level (11.0 percent)in 1999-2000 as in

1988-89, even thoughthis period spans the longest sustainedeconomic

expansion,andthe largestdeclinein unemployment,on record.

We next divide the growthin nonemploymentalong a second dimension. The percentageof weeks spent out of work is equal to the sum of

two components:the fractionof men who did not workat all overthe year

(for whomthe fractionof weeks spentout of workis 100 percent)andthe

fractionof weeks spentout of workfor those who workedsome positive

amount(multipliedby the fractionof menwho workedat leastone week).

In what follows we refer to these two componentsas "full-yearnonemployment"and "part-yearnonemployment,"

respectively.This decompositionallows us to examinehow muchof the growthin nonemploymentis

accountedfor by men with very long stretchesof joblessness-that is,

spells thatareso long thatmendo not workat all duringa calendaryearandhow muchis due to men with "transitory"

jobless spells.

b. a.

Source:

Period

1972-73

1988-89

1982-83

1991-92

1978-79

1975-76

1971-72

1967-69

Number

1999-2000

of

Unemployed

Authors'

weeks

plus

in

Units

Table

as 2.

indicated

calculations

indicated

Peak Peak Peak Peak Peakbusiness

Phase

based Trough

Trough

Trough

Trough

nonparticipating;

of

status

on

Unemployment,

cycle

detailsMarch

divided

may

by

CPS

not52.

data.

sum

3.06.34.39.04.36.93.84.52.2

to

Nonparticipation,

Labor

Unemployed

totals

and

force

because

of

status

rounding.

8.07.56.76.35.95.65.04.94.1

(percent Nonemployment

of

Nonparticipating

during

calendar

13.811.0

15.2

11.0

10.212.4

8.89.46.3

yeara)

Nonemployedb

Business-Cycle

Peaks

and

-3.32.0-4.74.6-2.53.0-0.72.3

(percentage

Change

in

unemployment

Troughs,

points)

1967-2000

0.50.80.50.40.30.60.10.8

(percentage

Change

in

nonparticipation

points)

94

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

The results,shownin table 3 and figure4, are striking.The amountof

joblessness accountedfor by those workingat least partof the year was

only slightly higherin 1999-2000 than in 1967-69 (4.9 versus 4.5 percent). But the amountof joblessness accountedfor by those who did not

workat all over the yearmorethantripled,from 1.8 percentin the 1960s

to 6.1 percentin 1999-2000. Moreover,whereaspart-yearnonemployment declined by 4.5 percentagepoints from its recessionarypeak in

1982-83 to 1999-2000, full-yearnonemploymentincreasedslightly.This

is particularlystrikinggiven that the interveningperiodis characterized

by two of the longesteconomicexpansionson record.

Whatexplainsthis trendtowardlong-termjoblessness?Onepossibility

is that those men with the least favorablelabor marketprospectshave

simplydroppedout of the labormarket:the so-calleddiscouragedworker

effect. Figure5 addressesthis possibilityby disaggregatingnonemployment and nonparticipation,

respectively,by reportedreason.We distinthree

main

guish among

groups:those who reportedthat they could not

findwork,those who reportedthatthey wereill or disabled,anda residual

categorywe label "other."Overthe periodcoveredby ourdata,the figure

shows only a small increasein the proportionof men who reportedthat

theycouldnot findwork.Risingsharesof the "ill or disabled"and"other"

categoriesaccountfor the largest changes of both nonemploymentand

The largerimpactof the "ill or disabled"categoryis on

nonparticipation.

Table 3. Part-Yearand Full-Year Nonemployment,1967-2000a

Percentof calendaryear

Period

1967-69

1971-72

1972-73

1975-76

1978-79

1982-83

1988-89

1991-92

1999-2000

Phase of

business cycle

Part-yearb

Full-yearc

Total

Peak

Trough

Peak

Trough

Peak

Trough

Peak

Trough

Peak

4.5

6.5

6.0

8.4

6.8

9.4

6.5

7.7

4.9

1.8

2.9

2.8

4.1

3.8

5.8

4.6

6.0

6.1

6.3

9.4

8.8

12.4

10.2

15.2

11.0

13.8

11.0

Source: Authors' calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

a. Details may not sum to totals because of rounding.

b. Fractionof males nonemployed for part of the year multiplied by the average percent of the calendaryear spent nonemployed for this group.

c. Fraction of males nonemployed for the entire year multiplied by the percent of the calendar year spent nonemployed

(100 percent).

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

95

Figure 4. Part-Yearand Full-YearNonemployment,1967-2000

Percentof calendaryear

16 j2i~~~~~~~~~Total

141412 10

8-

6

2

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

Source: Authors' calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

a. Fractionof males nonemployedfor partof the year multipliedby the averagepercentof the calendaryear spent nonemployed

for this group.

b. Fractionof males nonemployedfor the entire year multiplied by the percent of the calendaryear spent nonemployed (100

percent).

the nonparticipation rate (middle panel of figure 5): men in this category

account for about 42 percent (0.8 out of 1.9 percentage points) of the

increase in nonparticipation between 1982-83 and 1999-2000. The rest is

"other."The bottom panel of figure 5 narrows the focus to men who were

full-year nonworkers, for whom the effect of rising disability is more

prominentstill. Virtuallynone of the long-termincreasein full-yearjoblessness is accounted for by discouraged workers: the "other" category

and persons reportingjoblessness for health reasons account for the secu-

lar increase.

A largeliteratureexaminesthe impactof changesin the disabilitybenefits programon the labormarketparticipationof male workers.17These

papersdocumenta substantialgrowthin the disabilityrolls in the early

17. Parsons(1980); Bound (1989); Bound and Waidmann(1992); Autorand Duggan

(forthcoming).

Figure 5. Nonemploymentand Nonparticipation,by ReportedReason, 1967-200a

Percentof calendaryearNonemployment

16 14 12 -

10

8

Ill or disabled

6

Nonparticipatiaoknvaiabl

9

87

6

5

4

Ill or disabled

3

2

91

Full-year nonemployment

9

8

7

65

43

Ill or disabled

2

1970

1975

18

Source: Authors'calculationsbased on MarchCPSdata.

a. Excludes individualswho reportbeing studentsor retired.

195

1990

1995

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

97

1970s, linked to the sharpdecline in participationamong older males.

Becauserealwages were risingfor the most partover this period,the earlierepisodeis consistentwitha reductionin laborsupplyin responseto the

improvingnonmarketalternativerepresentedby disabilitypayments.Durchangestighting the early 1980s,however,legislativeandadministrative

led

to

in new

these

standards

reductions

tighter

standards;

ened eligibility

awardsandterminatedbenefitsfor a substantialfractionof beneficiaries.

After 1984, eligibility criteriawere substantiallyliberalized,and this

led to increasedreceipt of disability payments.18 Examiningaggregate

time series as well as cross-statevariation,John Bound and Timothy

Waidmannconcludedthatvirtuallyall of the increasein nonemployment

amongthose reportingthatthey were ill or disabledin the CPS could be

explainedby increasedreceipt of disabilitybenefits.19Autor and Mark

Dugganconcludedthatliberalizationof eligibilityfor disabilityinsurance

interactswith adverse shifts in labor demand,as otherwiseemployable

over unemploymentor low-wage

men opt for subsidizednonparticipation

work.Figure6 offers indirectsupportiveevidenceon this point,comparing the changes in unemploymentand nonparticipationbetween peaks

and troughsof differentbusinesscycles. The figureshows thatincreased

nonparticipationaccountedfor a much largerfractionof rising nonemploymentin 1989-92 thanin earlierrecessions.The smallestcontribution

was in the recession of 1992, when eligibility rules

of nonparticipation

were tightened.The increasein nonemploymentamongthe ill or disabled

accountedfor nearly 16 percentof the total change in nonemployment

between 1989 and 1992 (not shown), a much higherproportionthan in

previousrecessions.Nonemploymentof the ill or disabledactuallyfell

during the 1982 recession, an observationthat also likely reflects the

tighteningof eligibilityrulesduringthis period.

Table 4 decomposes secular changes in nonemploymentbetween

1967-69 and 1999-2000, as well as over the 1990s. In the 1990s the data

indicate that roughlyhalf (0.8 percentagepoint) of the 1.5-percentagereflectsa shiftin laborsupplycausedby

pointincreasein nonparticipation

improving nonmarketalternativesto working. There is no reason to

believe thatthe healthof Americanmen deterioratedover the decade(and

Yet nonparticipation

caused

much reasonto believe that it improved).20

18. AutorandDuggan(forthcoming);BoundandWaidmann(2000).

19. BoundandWaidmann(2000).

20. See MurphyandTopel (2001), for example.

98

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

Figure 6. Changesin Unemploymentand NonparticipationEntering Recessions

Percentagepoints

5 -

0 Unemployment

E Nonparticipation

43-

2-

fAf?:$d9;

'S'

i;

1969-71

1973-75

.....

........

;.~~~~~~~~~~~~........

1979-82

1989-92

Source: Authors'calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

by self-reportedhealthreasonsincreasedby 0.8 percentagepointover the

decade.Unlike in the early 1970s, when real wages were risingrapidlyas

nonparticipationincreased,real wages remainedlow and were falling

over the firsthalf of the 1990s. This fact makesit moredifficultto parcel

out the componentdue to shiftinglabor supply.Yet with the increasein

real wages in the latter half of the decade, continuinggrowth of nonparticipationindicatesa shift in labor supply. In a manneranalogousto

interpretationsof the Europeanunemploymentexperience,the dataindicate thatthe interactionof disabilitybenefitsandlabormarketshocksmay

be of key importance in understandingrising rates of labor force

withdrawal.2'

Figure7 summarizesour previousresults,showinglong-termchanges

in three alternativemeasures of joblessness since the late 1960s. The

unemploymentrate shows the most dramaticimprovementof the three

measuresin the 1990s, nearlyreturningto 1960s levels. By this common

21. AutorandDuggan(forthcoming).

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

99

Table 4. Changes in Nonemployment,by Reported Reason for Nonemployment,

1967-2000a

Percentagepoints

Reasonfor nonemployment

No work

available

Illness or

disability

Other

Total

Change1967-69 to 1999-2000

Nonemployment

Outof laborforce

Unemployment

1.2

0.6

0.6

1.7

1.7

0.0

1.8

1.7

0.0

4.7

4.0

0.6

Change1988-89 to 1999-2000

Nonemployment

Outof laborforce

Unemployment

-1.9

-0.4

-1.5

0.8

0.8

0.0

1.1

1.0

0.0

0.0

1.5

-1.5

Measure

Source: Authors' calculations based on March CPS data.

a. Details may not sum to totals because of rounding.

Figure 7. Changesin Unemployed,Discouraged,and NonemployedWorkers Since

1967, 1967-2000

Percent

10

Nonemployed

Other

nonparticipating

8

6

4

2

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

Source: Authors'calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

a. Discouragedworkersare those who reportnot being employed because they were unable to find a job; they are not included

in the labor force.

100

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

measureof labormarketperformance,events have come full circle, and

one mightarguethatthe naturalrateof joblessnesshas returnedto previous low levels. Adding nonparticipantswho are discouragedworkers

changes the conclusion slightly, althoughthe figure also demonstrates

thattherehas been no reductionin discouragedworkerssince the 1980s.

to give totalnonemploymentchangesthe

Addingin othernonparticipants

interpretation

substantially.By this measuretherewas no improvementin

overalljoblessnessfromthe late 1980s to 2000, despitefallingunemploymentrates.In this sense, changesin unemploymentprovidea misleading

picture of changes in employmentopportunitiesand the likelihood of

findingwork.

The Incidence and Duration of Jobless Spells

The dataon full-yearnonemploymentsuggestthatthe concentrationof

unemploymentand nonemploymentincreased dramaticallyover the

periodcoveredby our data.Table 5 providesfurtherevidence, showing,

for variousperiods,the distributionsof spells of joblessnessduringa calendaryear. The trendtowardlong-termjoblessness is unmistakable.For

rate was 6.3 percent,

example, in the 1960s, when the nonparticipation

men who were jobless for the entireyear accountedfor 28.8 percentof

nonemployment.But by the end of the 1990s-when nonemployment

reached11 percent-full-year nonemploymentaccountedfor over half of

all joblessness. A similar patternholds for unemployment(table 6).

Althoughunemploymentratesin 1999-2000 were roughlycomparableto

those in the 1960s, the shareof unemploymentdue to shortspells (one to

thirteenweeks) fell by one-third,from30 percentto 20 percent.Individuals with more than six monthsof unemploymentaccountedfor about a

quarterof all unemploymentin the 1960s,but46 percentby the end of the

1990s. These shifts toward long-termjoblessness mean that particular

have much differentmeanrates of unemploymentand nonparticipation

ings todaythanin pastdecades.

To examinethe increasedimportanceof long spells more closely, we

use informationin the CPSto estimateboththe incidenceandthe duration

of jobless spells. Focusingfirston unemployment,we note thatthe rateof

unemploymentcan be decomposedinto the productof two components:

the probabilityof an individualenteringunemployment(the entryrate),

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

101

Table 5. Distributionof Nonemployment,1967-2000a

Percentof nonemployed

Numberof weeksa year

Period

1967-69

1971-72

1972-73

1975-76

1978-79

1982-83

1988-89

1991-92

1999-2000

2 orfewer

3 to 12

13 to 25

26 to 38

39 to 51

52

2.4

1.5

1.6

1.1

1.5

0.8

1.0

0.8

0.7

17.2

12.9

12.4

9.9

13.1

8.1

10.3

8.8

8.0

18.9

18.8

17.2

16.6

17.7

13.9

13.2

12.7

9.7

18.0

21.2

21.7

22.5

20.2

20.6

19.0

19.1

13.9

14.8

15.9

15.3

17.2

14.4

18.3

15.2

14.9

12.2

28.8

29.7

31.9

32.7

33.2

38.3

41.3

43.8

55.5

Source: Authors' calculations based on MarchCPS data.

a. Details may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

and the averagedurationof an unemploymentspell. Denote the instantaneous transitionratesfromemployment(e) andout of the laborforce (o)

to unemployment(u) at date t by Xeu(t) and XOu(t),respectively,and the

correspondingrates at which individualsleave unemploymentby Xue(t)

andXkj(t).Thenthe rateof changein the unemploymentrateis

(1)

du(t) =

dt

e(t)Xeu(t)

+ o(t)0ou(t)

- U(t)[Rue(t)

+

X0o(t)].

The steady-statefractionof weeks spentunemployed,[du(t)ldt= 0], correspondingto the entryandexit ratesat any given pointin time satisfies

Table 6. Distributionof Unemployment,1967-20O0

Percentof unemployed

Numberof weeksa year

Period

1967-69

1971-72

1972-73

1975-76

1978-79

1982-83

1988-89

1991-92

1999-2000

13 orfewer

14 to 26

27 to 39

40 to 49

50 to 52

30.3

20.4

20.6

17.8

27.0

13.7

22.6

16.9

20.4

42.3

40.6

39.9

31.2

34.2

28.9

33.5

31.7

33.4

14.9

21.5

21.0

22.8

19.0

21.7

18.5

20.6

18.2

8.9

10.9

10.4

14.5

11.8

17.9

14.8

16.4

14.6

3.6

6.6

8.2

13.7

8.0

17.7

10.5

14.3

13.4

Source: Authors' calculations based on MarchCPS data.

a. Details may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

102

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

()

u(t) = [1-uWWI

(2)

)

where

e (t)

X-(t) =

'u(t) =

Xue

X-eu(t)

+

o*

(t) X,u(t), and

(t) + X-u(t).

Here Xkis the rate at which individualsenter unemployment,being a

share-weightedaverageof entryratesfor personswho are employedand

those who are out of the laborforce. Similarly,X'(t) is the rateat which

individualsleave unemploymentby becomingemployedor by leavingthe

labor force. Since 1/X'(t) is the average durationcorrespondingto the

contemporaneousrateof exit from unemployment,and [1 - u*(t)]X.(t) is

the expectednumberof spells of unemploymentper year at the current

entry rate, equation2 has a naturalinterpretationin terms of entry and

duration.Growth in the steady-statefraction of the year spent unemployed can be decomposedinto growthin the probabilityof becoming

unemployed(entry)andthe averagedurationof unemploymentspells.

To implementthis frameworkempirically,we use two identitiesthat

correspondto equation 1 integratedover the year. The change in the

unemploymentratefromthe beginningto the end of yeart is

(4)

U,(t) - UO(t)

=

[1- U (t)]u () - U (0)u ('0,

where U1(r)is the unemploymentrate(measuredas a fractionof the population)at the end of yearX, UjQr)is the correspondingrateat the startof

the year, and U(t) is the averageunemploymentrateover the year.With

these definitions,Xu(t) andX' (t) are weightedaveragesof the instantaThe expected

neous transitionprobabilitiesto andfromunemployment.22

numberof spells of unemploymentover the yearis then

(5)

S(t) = Uo(t) + [1 - U

()r),

since spells are generatedeitherby startingthe year unemployed,UO(t),

or by becomingunemployedduringthe year, [1-U(r)]Xu(t). To estimate

the entryandexit parameters,we use the datafromthe CPS togetherwith

22. The weights in these weighted averages are (1 - u)(0) and u(O), respectively, where

e indexes weeks over the year.

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

103

monthly data on aggregaterates to interpolatethe startingand ending

numbersfor each year. Solving equations4 and 5 gives our estimating

equationsfor unemploymenttransitionsas

(6)

()

S(t)-U0(t)

1-U(t)

and

(7)

(u

S(t)- U,()

The resultingestimatesareshownin the top panelof figure8 andin the

first two data columns of table 7. For unemployment,the key findingis

thatan increasein durationsaccountsfor the entiregrowthin unemployment over the 1967-2000 period.The entryrateinto unemploymentwas

actuallylower in 1999-2000 (0.7 percenta month)thanit was in 1967-69

(1.1 percenta month),whereasdurationsof unemploymentspells doubled

from2.1 to 4.2 months.Notice fromequation3 thata decliningincidence

of unemploymentspells can be caused eitherby a decline in the rate at

which individualslose their jobs, Xeu(t), or by a decline in the rate at

which nonparticipantsstartto look for work, XOu(t).

These contributions

arenot separatelyidentified,althoughit is likely thatthe o -* u transition

has declined substantiallyas nonparticipationhas become a permanent

laborforce state for largernumbersof men. In any case, we cannotconclude fromtable6 andfigure8 thatthe e -* u transitionhas declined,that

is, thatjobs have becomemore stable.

Accordingto figure8, untilthe recessionof 1991-92, cyclical fluctuations in unemploymentwere drivenby changesin boththe incidenceand

the durationof spells, with roughly equal weights on each component.

But rising incidence played a minor role in the recession of 1991-92,

while durationssoared. Indeed, unemploymentdurationsin 1993 were

virtuallythe sameas in the recessionyear 1983, whichwerethe highestin

all the yearsof our data,while the entryratewas about25 percentlower.

The ensuingdeclinein unemploymentover the remainderof the decadeis

drivenalmostentirelyby reducedprobabilitiesof becomingunemployed;

durationsof unemploymentremainedhigh. From these data it appears

that the main characteristicof the 1990s is that the historic correspondence between the incidence and the durationof unemploymentspells

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

104

Figure 8. EstimatedEntry Rates and Durationsfor Unemploymentand

Nonemployment,1967-2000

Unemploymenta

Monthsa year

Percenta month

2.2 -

Duration

(rightscale)

2.0 -

A"

5.0

/

1.8-

,*/13

{/

\~~~~~~~~~~~

04

1

45

1.61.4 --3.5

- 3.0

0.8

2.5

Entry rate

,'

(leftscale)

_ 2.0

0.6 _ _

l

l

l

l

I

l

Nonemploymentb

Duration

(rightscale)

2.2 -

4

,

2.0 -

1

1.8 -

,1

1.6 11.4 -(left

10

scale)

1.2

8

6

0.8

0.6 _

l

l

l

l

l

I

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

Source: Authors'calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

a. Estimatedfrom the numberof spells using equations5, 6, and 7.

b. Based on incidence of nonemployment;see text for details.

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

105

Table 7. Estimated Entry Rates and Durations of Unemploymentand

Nonemployment,1967-2000

Units as indicated

Unemploymenta

Nonemploymentb

Phase of

businesscycle

Entryrate

(percenta

month)

Duration

(months)

Entryrate

(percenta

month)

Duration

(months)

1967-69

1971-72

1972-73

Peak

Trough

Peak

1.1

1.5

1.4

2.1

3.2

2.9

1.0

1.2

1.1

6.7

8.6

8.5

1975-76

Trough

1.8

4.1

1.5

9.6

1978-79

1982-83

1988-89

1991-92

1999-2000

Peak

Trough

Peak

Trough

Peak

1.5

1.9

1.3

1.5

0.7

3.1

5.1

3.5

4.5

4.2

1.4

1.5

1.1

1.3

0.8

8.4

12.0

11.0

12.4

15.1

Period

Source: Authors' calculations based on March CPS data.

a. Estimatedfrom the numberof spells using equations 5, 6, and 7.

b. Based on incidence of nonemployment;see text for details.

came to an abruptend. Withfewerbutlongerspells, the populationdistributionof unemploymentis muchmoreconcentratedthanin earlieryears.

The last two columnsof table 7 andthe bottompanelof figure8 show

correspondingcalculationsfor the incidenceanddurationof nonemployment spells. In the case of nonemployment,the CPS does not provide

informationon the numberof spells in a calendaryear-separate spells of

arenot recorded-and so we use dataon the incidenceof

nonparticipation

nonemploymentover the year (thatis, the fractionof men with positive

weeks of nonemployment)to infer the entry rate.23These calculations

show thatthe contrastbetweenentryand durationis even more extreme

than in the case of unemployment.As with unemployment,the rate of

entryto nonemploymentis actuallylowerin 1999-2000 thanit was in the

1960s, but durationsshow a steady upwardtrend over the thirty-four

23. The fractionof individualswho experiencezero nonemployment(thatis, who are

employedfor the full year)is given by F(r) = Eo(r)exp[-12X*(r)],whereX*(t)is the average monthlynonemploymenthazardover the yearfor individualswho havenot yet entered

nonemployment,andEj(t) is the employmentrateat the startof the year.In general,X*(1t)

for the populationof

<X (t), whereX (t) is the averagerateof transitionto nonemployment

employedpeople.This will cause our estimatesof entryandexit ratesto be biaseddownward.We attemptedto assess the magnitudeandvariabilityin this bias with similarcalculations for unemployment,where the numberof spells is recorded.In that case the bias

variedlittle over time, lendingsome confidencethatthis methodshouldnot be too faroff.

106

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

yearscoveredby ourdata,withno sign of slowergrowthin the 1990s. By

the end of the decadethe averagedurationof nonemploymentspells was

over fifteenmonths,which is morethandoublethe lengthof spells in the

late 1960s. The averagedurationof spells rose by over fourmonthsfrom

the late 1980s to 1999-2000, reflectingthe increasingproportionof men

who have simplyquitthe laborforce.

Table 7 and figure8 painta clear picture.Althoughthe ratesof entry

into unemploymentand nonemploymenthave returnedto or even fallen

below levels experiencedduringthe late 1960s, the durationsof jobless

spells aremorethantwice as long at the end of the period.Indeed,jobless

spells were longer in 1999-2000 than at any previous cyclical low of

unemployment,andthey exceededthe averagedurationof spells over the

whole period of the data. It should be clear from these data that the

employmentpatternsof the late 1990s resemble other periods of low

unemployment-the late 1960s in particular-only in termsof the overall

rate of unemploymentand the rates at which individualsenterjoblessness. The durationsof spells arevery differentandvery muchlonger.For

the typicalworker,the occurrenceof a jobless spell is a fardifferentevent

thanit was in the past.

Unemployment,Nonemployment,and Wages

Our previous analysis of wage and employmentdata through 1989

foundthatthe patternsof changein unemploymentand nonemployment

variedsignificantlyacrossskill groups,as definedby percentileintervals

of the overall wage distribution.Figure 9 and table 8 summarizeour

results based on wage percentilegroupingsfor the period 1967-2000.

Table 8 recordschanges in unemployment,nonparticipation,and total

joblessness between 1967-69 and 1988-89 (the end of the data in our

1991 paper),between 1988-89 and 1999-2000, and over the full period

of ourdata.

All componentsof nonemploymentincreasedthe most for low-wage

workers,especiallybefore 1989. Overthe 1990s, nonparticipation

continued to rise while unemploymentratesdeclinedsharply.Reversingprevious trends,in the 1990s bothunemploymentandoverallnonemployment

fell the most for workersin the bottom 10 percentof the wage distribution. Otherlow-wage groupsalso experiencedlower unemploymentover

Figure 9. Unemployment,Nonparticipation,and Nonemployment,by Wage

PercentileGroup, 1967-2000

Unemployment

Percentof calendaryear

16

I tol /s0

-- l to 20

21 to 40 1_

-------41to 60 ''\

\

12

8-

Nonparticipation

20 15 10

S __-'

5,,

.

.

.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

.....

...,,,,,,.,,

.....------.----

Nonemployment

35

3025 20

1970

1975

1980

Source: Authors'calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

1985

1990

1995

108

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

Table 8. Changesin Unemployment,Nonparticipation,and Nonemployment,by

Wage Percentile Group, 1967-2000

Percentagepoints

Wagepercentilegroup

Period

I to 10

11 to 20

21 to 40

41 to 60

61 to 100

Unemployment

1967-69 to 1988-89

1988-89 to 1999-2000

1967-69 to 1999-2000

6.4

-4.6

1.8

4.9

-3.1

1.8

2.6

-1.6

1.1

1.5

-1.0

0.5

0.3

-0.5

-0.1

Nonparticipation

1967-69 to 1988-89

1988-89 to 1999-2000

1967-69to 1999-2000

10.9

0.8

11.7

7.2

2.4

9.5

2.9

2.6

5.5

1.3

1.3

2.6

0.0

0.9

0.9

Nonemployment

1967-69 to 1988-89

1988-89 to 1999-2000

1967-69 to 1999-2000

17.3

-3.8

13.5

12.1

-0.8

11.3

5.6

1.0

6.6

2.8

0.3

3.0

0.3

0.4

0.8

Full-yearnonemployment

1967-69 to 1988-89

1988-89 to 1999-2000

1967-69 to 1999-2000

10.2

1.7

12.0

6.3

2.7

8.9

2.9

2.4

5.4

1.6

1.3

2.9

0.5

0.9

1.4

Source: Authors' calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

the decade,althoughnonemploymentwas largelyunchangedfor workers

above the bottom 10 percent,reflectingrising rates of laborforce withdrawal. Even with the sharp decline in unemploymentfor low-wage

workersin recentyears,however,for the full periodbothunemployment

andnonemploymentincreasedmost amongthe least skilled.Nonemployment rose by roughly 12 percentagepoints for the two lowest wage

groups,but by less than 1 percentagepoint for men above the 60th percentile of the wage distribution.For workersnearthe median(percentiles

41-60), unemploymentwas essentiallyunchangedover the period as a

whole, yet nonemploymentincreasedby 3 percentagepoints.

Cyclicalincreasesin joblessnessareknownto fall most heavilyon the

least skilled. Figure 10 comparesthe skill distributionsof cyclical and

secularchangesin nonemployment.Foreach of the wage intervalsshown

in table 8, the figure shows the averagecyclical change in jobless time

going into and out of four recessions(1970-71, 1975-76, 1982-83, and

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

109

Figure 10. Cyclical and Secular Changesin Nonemployment,by Wage Percentile

Group, 1967-2000

Percentage pointsa

EJAverage over recessionsb

1967-69 to 1988-89

* 1988-89 to 1999-2000

*

15 -

10

-

5

0

I

to 10

II to 20

21 to 40

41 to 60

61 to 100

Source: Authors' calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

a. Change in the percentof weeks a year nonemployed.

b. Average change entering(troughminus peak) and exiting (peak minus trough)four recessions (1970-71, 1975-76, 1982-83,

and 1991-92).

1991-92),24the secular change between the cyclical peaks of 1967-69

and 1988-89 (the period covered in our 1991 paper), and the shorter

secular change over the more recent 1988-89 to 1999-2000 period.

Comparedwith business-cycleincreasesin nonemployment,the secular

changein nonemploymentfromthe late 1960s to the late 1980s was much

more skewed towardlow-skilled men, with virtuallyno impact on persons above the medianof the wage distribution.The secularmovement

over the recentperiodis morenearlyskill neutral,with the exceptionthat

nonemploymentfell significantlyfor men in the first decile of the wage

distribution.In this sense the 1990srepresenta smallreversalof declining

24. We measurethis by the averageof the changegoing into andout of each recessionary period. The periods are defined using the same year groupingsused in the tables:

1967-69, 1970-71, 1972-73, 1975-76, 1978-79, 1982-83, 1988-89, 1991-92, and

1999-2000.

110

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

employment opportunitiesamong the least skilled. We relate these

changes to concomitantchanges in the distributionof wages below, but

firstwe takea briefdetourto explorean alternativeexplanationfor changingjobless ratesamongprime-agedmen, namely,the labormarketopportunitiesof theirwives.

Did Working Wives Shift Male Labor Supply?

It remainsour view that long-termchanges in male joblessness were

drivenby changesin labordemandthatdisproportionately

affectedlessskilled workers. These adverse demandconditions continued into the

1990s, althoughsomewhatmitigated,so thatnonemploymentcontinued

to rise even as measuredunemploymentwas falling. An alternative

explanation-with far differentwelfare implications-is that increased

wages andgreaterlaborforce participationof womenhave shiftedmen's

laborsupply:as the labormarketopportunitiesof wives improved,husbands chose to work less and household utility rose. On this view, at

least partof the long-termincreasein nonemploymentamongmen represents a welfare-improvingchangein householdlaborsupplydecisions.

Table9 andfigure11 explorethis issue. Table9 recordsmale earnings,

the percentageof householdswith a workingwife, averageearningsof

wives, and averagehouseholdincome for householdsin differentpercentilesof the malewage distribution.Amongless-skilledmen,wherethe

largest increasesin nonemploymentoccurred,the percentageof households with a workingwife actuallyfell over time. For these men, declining marriageratesoffset increasedlaborforce participationof women, so

that fewer low-wage men today reside with a working wife. For lessskilled men, averagehouseholdincome (which includes earningsof all

household members)increasedonly slightly from 1972-73 (when the

trendtowardrising inequalitybegan) to 1999-2000: averagehousehold

income rose by 11 percentin each of the percentileintervals1-10 and

21-40; in these groups, increases in the average earningsof working

wives by 40 percenthelpedto offset decliningmale earnings.In contrast,

the presenceof a workingwife is both higher and rising in households

above the 60th percentileof the male wage distribution,where men's

wages were rising and employmentrateswere stable.The shareof these

householdsin which a workingwife was presentincreasedby 9 percentage pointsafter1972-73 andby 12 percentagepointsfromthe 1960s, and

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

111

Table 9. HouseholdEarnings Characteristics,by Wage PercentileGroup, 1967-2000a

1996 dollarsa year,exceptwherenotedotherwise

Item

1st to I Othpercentile

Maleearnings

Percentof households

with workingwife

Wife's earningsb

Householdincome

21st to 40thpercentile

Maleearnings

Percentof households

with workingwife

Wife's earnings

Householdincome

61st to I 00thpercentile

Male earnings

Percentof households

with workingwife

Wife's earnings

Householdincome

All households

Maleearnings

Percentof households

with workingwife

Wife's earnings

Householdincome

1999-2000

1967-69

1972-73

1978-79

1988-89

11,134

11,354

11,479

8,625

9,584

38

3,050

22,965

36

3,392

26,366

36

3,766

28,140

31

3,975

25,952

29

4,770

29,194

23,746

25,213

23,579

21,522

21,507

49

5,132

35,394

48

5,773

39,137

48

6,133

40,770

46

7,410

40,773

40

8,091

43,431

44,213

49,375

47,147

51,449

59,843

41

4,786

54,456

45

5,918

61,722

50

7,219

61,861

55

11,537

71,937

54

14,993

88,507

31,230

34,121

32,686

33,193

36,789

44

4,713

42,263

45

5,548

47,538

48

6,388

48,560

49

8,895

52,821

45

10,854

61,541

Sources: Authors' calculationsbased on MarchCPS data and Economic Reportof the President, 2001.

a. Earningsand household income are deflated by the price index for personal consumptionexpenditure.Male's and wife's

earnings include income from wages, salary, and self-employment; household income includes all sources of earned and nonearned income of all household members.

b. Average of wife's earningsfor all males in the sample; the observationis zero when there is no working wife.

the averageearningsof these wives increasedby 153 percentbetween

1972-73 andthe end of the century.

It is difficult to square these facts with the view that long-term

increases in labor force withdrawalamong men have been driven by

improvedlabormarketopportunitiesfor theirwives. To settle the issue,

figure 11 shows changes in unemployment,nonparticipation,and fullyearnonemploymentfor men with andwithoutworkingwives. The clear

patternis thatrisingunemploymentandlaborforce withdrawalhave been

concentratedamongmen who do not have a workingwife. The contrastin

trendsis particularlystrikingfor nonparticipationand full-yearnonemployment,where men without a workingwife have steadily withdrawn

Figure 11. Male Nonemploymentand Nonparticipation,with and withouta Working

Wife, 1967-2000a

Nonemployment

Percentof calendaryear

20

Withoutworkingwife

15

Withworkingwife

Nonparticipation

12

F

10

86

42 -

Full-yearnonemployment

10

86 4 2

-

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

Source: Authors'calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

a. To qualify as a workingwife, the wife must both live with her husbandand have workedat least one week duringthe previous year.

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

113

fromregularemployment.Fromthese datawe concludethata theorybuilt

on shifts in householdlaborsupplywill not go far in explainingchanges

in malejoblessness.

Wage Changes, Labor Supply, and Nonemployment

So far our discussionhas focused on changes in unemploymentand

nonemploymentover time. Figure 1 andtable 1 showedthatmanyof the

same patternsobservedwith regardto employmentand unemployment

hold for realwages. Inequalityin realwages grew significantlyfrom 1970

to 1990 across the full range of the wage distribution.Since 1990,

inequalityhas continuedto increaseat the top of the wage distribution,

but inequalityhas held steady or even narrowedslightly at the bottom:

both low-wage and middle-wage workers experienced real wage

increasesstartingaround1995. These increasesin real hourlywages representthe first significantgrowthin real wages for low- to middle-wage

males since the early 1970s. According to our earlier analysis, rising

wages for these groupsshouldlead to increasedemploymentrates,especially amongthe least skilled, for whom we concludedthatlaborsupply

elasticitieswere largest.

At a generallevel, trendsin nonemploymentby wage percentilegroup

(bottompanelof figure9) andtrendsin real wages for these same groups

(figure 1) reveal a similarpattern.In both cases low-wage workersfared

far worse thantheirmiddle-andhigh-wagecounterpartsfor muchof the

sampleperiod,and in both cases the divergencestops in the 1980s (after

roughly 1983 in the case of employment,and afterroughly 1989 in the

case of wages). Ourearlierpaperformalizedthis connection,arguingthat

declining rewardsto work provokedlabor supply responsesfrom lessskilled workers, who chose to work less. To what extent does the

demand-drivenexplanationwe stressedin our earlierpaper-that individuals respondto changingreal wage opportunities-help us to understand the changes since 1989 in employmentfor men in differentskill

categories?

Table 10 presentsestimatedpartiallabor supply elasticities obtained

fromcross-sectionaldatafor the years 1972-73 and 1988-89.25Ourestimates correspondclosely to those reportedin our earlier paper. They

25. To obtain these elasticities,we fit a quadraticfunctionusing averagewage and

employmentdataby percentilecategory.We reportthe slope at each percentile.

114

BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity,1:2002

Table 10. EstimatedLabor Supply Elasticitiesand Changesin Nonemploymentand

Wages, 1972-2000a

Unitsas indicated

Wagepercentilegroup

Partial

labor

labor

supply

elasticityb

Change inn

nonem

Changein

real lognoepymt

log

real

~~(percentagepoints)

hourlywage

(percent)

Predicted

Actual

1972-73 to 1988-89

1 to 10

11 to 20

21 to40

41to60

61 to lOO

Entiresample

0.287

0.217

0.170

0.126

0.048

n.a.

-24.8

-22.3

-16.5

-9.2

-0.2

-9.9

7.0

4.7

2.7

1.1

0.1

2.0

10.2

5.7

2.6

0.8

-0.1

2.2

1988-89 to 1999-2000

1 to 10

llto20

21 to40

41 to 60

61 to 100

Entiresample

0.287

0.217

0.170

0.126

0.048

n.a.

2.3

-0.4

-1.5

-1.2

7.0

2.4

-0.7

0.1

0.3

0.2

0.1

0.1

-3.8

-0.8

1.0

0.3

0.4

0.0

Source: Authors' calculationsbased on MarchCPS data.

a. Laborsupply elasticities and observed changes in real wages are used to predictthe change in nonemployment.

b. Elasticities in both panels are estimated using cross-sectional data on average wage and employment, by percentile, for

1972-73 and 1988-89.

show substantiallyhigherelasticitiesat low wages:the employmentrates

of less-skilled workersare more responsiveto wage changes. The top

panel of the table illustratesthe fact thatthe large wage declines (shown

in the second data column),togetherwith the estimatedelasticities,can

accountfor mostof the rise in nonemploymentfrom 1972-73 to 1988-89.

The bottompanelof the tableuses the same laborsupplyelasticitiesestimatedfrompre-1990data,togetherwith post-1989wage changes,to predict changesin nonemploymentduringthe 1990s. Thereis a reasonable

correspondencebetweenthe predictedandthe actualchanges:we predict

an improvementin employmentfor the lowest wage groupandsomewhat

worseningconditionsfor the othergroupsbelow the median.Yet we also

the improvementin employmentfor the least-skilledgroup.

underpredict

Althoughwages and employmentare obviously linked in the long run,

our interpretation

of the resultsis thatthe laborsupplymodel is less successful in predictingthe dynamicsof employmentandwage changesover

ChinhuiJuhn, KevinM. Murphy,and RobertH. Topel

115

a relativelyshortperiod.Notice also thatemploymentgains precededthe

recoveryin wages among the least skilled, which is inconsistentwith a

purelaborsupplyexplanationof changingemploymentrates.

Conclusion

We have examinedunemploymentandnonemploymentamongprimeaged males in the United States using thirty-fouryears of data on labor

marketoutcomes. Although recent unemploymentrates have fallen to

rates

levels reminiscentof the 1960s, we findthatrisingnonparticipation

have offset reductionsin unemployment,leaving nonemploymentrates

unchanged.The rise in nonparticipationappearsto be due to both an

expansionof the disabilitybenefits program-as previous researchhas

argued-and continuedlow levels of real wages of less-skilledmen during the 1990s.

in the

Comparedwith earlierdecades,the increasein nonparticipation

skill

groups.Employmentratesof