Recent Changes in Health Policy for Low-Income People in Alabama

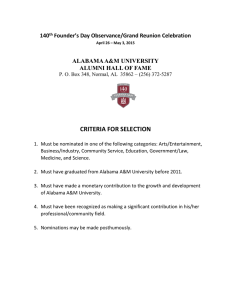

advertisement