7. Power in teams: effects of team power structures

advertisement

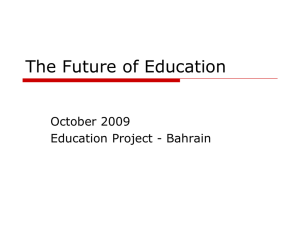

7. Power in teams: Effects of team power structures on team conflict and team outcomes Lindred L. Greer Power is my mistress. I have worked too hard at her conquest to allow anyone to take her away from me. Napoleon Bonaparte (1804/2014) Imagine a team full of such Napoleons called to work together. Would they conquer the world or fall prey to internal power struggles and conflicts and implode? While an abundance of research exists on the effects of power on individual affect, behavior, and cognition (for reviews, see: Guinote, 2007; Keltner et al., 2003), research which addresses the role of power in social contexts and can provide answers to the question posed above has only recently begun to emerge. In this chapter, this new and growing line of research on the effects of team power structures on team conflict and team outcomes is reviewed, an integrative theoretical framework for research in this area is developed, and interesting topics for future research are proposed. Across social and behavioral sciences, there is growing agreement among scholars that power refers to the asymmetric control of valued resources in social relations (for example, Blau, 1964; Emerson, 1962; Keltner et al., 2003; Magee and Galinsky, 2008; Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978; Thibaut and Kelley, 1959). Defined as such, there is extensive research on what power does to individuals (for recent reviews: Fiske and Berdahl, 2007; Guinote, 2008; Keltner et al., 2003) and intergroup relations (for example, Ebenbach and Keltner, 1998; Ellemers, 1993). Among the more important effects of having power at the individual level of analysis is the activation of individual approach systems (Keltner et al., 2003; Lammers et al., 2009), which induce feelings of control and optimism, abstract information processing tendencies, and motivational drives to pursue goals. Accordingly, research has shown that individual power increases positive affect (Keltner et al., 2003), abstract thinking (Smith and Trope, 2006), and pro-­active, goal-­oriented, impulsive, and risky behavior (Anderson and Galinsky, 2006; Guinote, 2007; Smith-­ Lovin and Brody, 1989). However, this past research has primarily looked at power in isolation. The role of power in interdependent team settings, in which multiple high-­power individuals, or Napoleons, may potentially interact is only now emerging (compare with Mannix and Sauer, 2006). In this new line of work, power structures in teams can be understood as existing based on the composition of the individually held power of individual team members. In these team settings, multiple dimensions of power (for example, expertise, charisma, legitimate authority, French and Raven, 1959; global versus local sources, compare with Groysberg et al., 2011; social versus personal power, Lammers et al., 2009) may feed into the overall level of power held by each individual in the team. Indeed, expectation states theory (Berger et al., 1972) makes a similar argument – any individual characteristic that is perceived in a team setting may be used by others to form 93 AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 93 30/04/2014 14:55 94 Handbook of conflict management research ­ erformance expectations. This means that the amount of power that an individual team p member may hold is infinite, and that all members in a team may potentially hold high levels of power. If one member has power, it does not necessitate that other members have less power, as often assumed in past work on power (for example, Blau, 1964; Emerson, 1962). Rather, members may all have similar overall levels of power, in part due to drawing on different bases, or types, of power. The potential for complexity and nuance in such power structures in team settings provides a rich and intriguing basis to further studies of social power. Three primary types of team power structures have been examined in research thus far – team power level, team power dispersion, and team power variety.1 Firstly, team power level is defined as the mean level of individual-­member power in the team (Greer et al., 2011a; Greer and Van Kleef, 2010; Sassenberg et al., 2007). Examples of teams with high power would include management teams or policy-­setting teams within an organization. Low-­power teams could include factory-­line teams or teams composed of entry-­level employees. Secondly, team power dispersion, or hierarchy, is defined as the spread of power within the team. High power dispersion would exist in a team in which power is concentrated in an all-­powerful leader and a subgroup exists within the team with virtually no power. Low power dispersion would exist if all members in the team held similar levels of power within the team. Thirdly, team power variety is defined as the degree to which members in the team draw their power from different sources. High power variety would exist when each member drew their power from a different source, such as task knowledge, legitimate authority, and punishment capacity. Low power variety would exist when all members draw their power from the same sources, such as the same form of task knowledge.2 In this chapter, the theory underlying the expected influence of these power structures on team conflict and performance is explicated, and empirical findings on these proposed relations are reviewed. Additionally, potential interactions among the different forms of power structures are explored and reviewed, and the moderating role of perceptions of power structures in the team, including perceived congruency and legitimacy, are also discussed. For an overview of the theoretical framework put forward here, please see Figure 7.1. TEAM POWER LEVEL Team power level, is defined as the mean level of individual-­member power in the team (Greer et al., 2011a; Greer and Van Kleef, 2010; Sassenberg et al., 2007). As with individual power, team power can activate approach systems of individual team members, and thereby of the team as the whole. This may have both positive and negative effects on teams. A literature specifically focused on the benefits of team power is the literature on shared leadership. In this field of research, scholars posit that increasing the power level of employees in a team should promote positive influence processes in the team, such as voice and participation in decision making (compare with Katz and Kahn, 1978). Positive influence processes such as voice can help improve team performance (De Dreu and West, 2001). Voice improves the exchange and integration of information in teams (Edmondson, 1999; Stasser and Titus, 1987), creates a cooperative and AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 94 30/04/2014 14:55 95 AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 95 30/04/2014 14:55 Key Theoretical Mechanisms: Positive - Increases role clarity - Reduces social comparison over power Negative - Creates silos and subgroups - Reduces superordinate team identity Key Theoretical Mechanisms: Positive - Meets members’ need for structure - Facilitates coordination and cooperation Negative - Heightens perceptions of inequality - Inefficiencies in communication Key Theoretical Mechanisms: Positive - Increases member voice - Raises empowerment and participation Negative - Increases threat and distrust between members - Increases intragroup power struggles Figure 7.1 Theoretical model of the effects of intrateam power structures Team Power Variety Team Power Dispersion Team Power Level Team Power Structures: Team Power Perceptions: Congruency Legitimacy Intragroup Conflict Performance Creativity Viability Team Outcomes: 96 Handbook of conflict management research supportive atmosphere in teams (Campion et al., 1993; Mumford and Gustafson, 1988), and gives members the feeling that they have a substantial control over the manner in which decisions are made (Thibaut and Walker, 1975), which makes them more accepting of and committed to group decisions (Fiol, 1994; King et al., 1992; Schweiger et al., 1989). Taken together, when team power level is high, members may be more likely to express their opinions, and positive influence processes such as voice can emerge, which make members more motivated, committed, and likely to expend effort on group tasks, thereby improving team performance However, team power can also activate feelings of threat and distrust. Those in power are motivated to retain the power that they hold (Bruins and Wilke, 1992; Elangovan and Xie, 1999; Maslow, 1937; Maner et al., 2007; Mulder, 1977). Holding power and authority becomes a part of one’s identity (DeRue and Ashford, 2010), and as such, members are motivated to protect this positive identity. Members are therefore vigilant in watching for threats to their position (for example, Isen and Geva, 1987; Tetlock, 2002). When they see other high-­power members behaving assertively and even claiming resources (choice assignments, control over subordinates, and so on) for themselves (De Cremer and van Dijk, 2005), members of high-­power teams may feel threatened and that they may lose their position (Georgesen and Harris, 2006; Scheepers and Ellemers, 2005). Put differently, in high more than low-­power teams, individuals are more distrusting of their peers’ approach-­oriented behaviors, are more easily threatened and anxious about their position of power within the team, and are likely to make hostile attributions – ­explanations of others’ ambiguous behavior as malevolent and ill-­intended (Rubin and Brown, 1975). Together, this implies that team power level may increase intragroup conflicts and harm team performance. Taken together, team power level appears to have the potential for both positive and negative effects on team performance. Review of Empirical Findings on Team Power Level Initial research has shown support for the positive and negative view of team power-­ level. The primary support for the positive perspective on team power can be found in the shared-­leadership literature. This literature suggests that sharing leadership influence, or power, across team members improves members’ empowerment and voice in the team, thereby improving member commitment and information exchange, and ultimately team effectiveness. Much support has been found for these propositions (for example, Carson et al., 2007; Klein et al., 2006; Pearce and Sims, 2002), suggesting that team power level may also set into play positive voice processes and improve team performance. However, there is also much support for negative effects of team power level. In the negotiation realm, research has shown that two high-­power negotiators are more distrusting of each other than two low-­power negotiators (De Dreu et al., 1998; Giebels et al., 2000). Similarly, Chattopadhyay et al. (2010) show that when multiple high-­status surgeons interact in a hospital team, conflicts occur and performance suffers. Greer et al. (2010) find in two studies of teams in the telecommunications and financial sectors that when teams have multiple high-­power members, teams have higher levels of conflict (particularly logistical process conflicts) and thereby lower levels of team performance. Groysberg et al. (2011) document a similar phenomenon – they find that teams can have too many stars. They show that while a certain number of star team members are good AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 96 30/04/2014 14:55 Power in teams ­97 for team performance, teams populated by a high proportion of stars have actually lowered financial performance. They speculate, similar to other work in this area, that this occurs because of conflict and coordination issues among star, or high-­power, team members. Ronay et al. (2012) also show that high-­power individuals working together have more conflicts than low-­power teams, and that this conflict negatively relates to team outcomes. Similarly, Porath et al. (2008) find that high-­status men were the most likely to retaliate against status contests from other men, further suggesting that conflicts and power struggles are more likely in interactions among those high in status and power than those low in status and power. Lastly, Kwaadsteniet and van Dijk (2010) show that in situations where tacit coordination is required, groups have much more difficulty coordinating action when all members have high status, rather than low or differentiated status. Therefore, across these different areas of research, the finding that teams with multiple individuals with high power and status have conflict and coordination problems and lower team outcomes appears to be very robust. However, these dynamics stand in stark contrast to the benefits of high team power as espoused in the shared leadership literature. Therefore, understanding when and why team power level activates positive more than negative team processes is a critical question for future research. TEAM POWER DISPERSION While power level refers to the average level of power held by members in the team, team power dispersion refers to the differences between members in their level of power within the team. Team power dispersion can be seen as a form of team hierarchy. Hierarchy is defined as “an implicit or explicit rank order of individuals or groups with respect to a valued social dimension” (Magee and Galinsky, 2008, p. 354). The benefits of team power dispersion, as a form of intrateam hierarchy, have been recently extolled in several theoretical reviews (such as: Halevy et al., 2011; Keltner et al., 2008; Magee and Galinsky, 2008). For example, Halevy et al. (2011) proposed that team power dispersion, or hierarchy, benefits teams and organizations through five key benefits: (1) creating a psychologically safe environment, including satisfying basic needs for power and structure; (2) motivating performance through hierarchy-­related incentives; (3) capitalizing on the complementary effects of having versus lacking power; (4) supporting division of labor and coordination; and (5) reducing conflict and encouraging voluntary cooperation. Magee and Galinsky (2008) are more neutral regarding the effectiveness of hierarchy, but suggest that hierarchies are difficult to avoid and highly self-­sustaining. Lastly, Keltner et al. (2008) focus on how hierarchies provide a useful decision-­making heuristic in teams, facilitating the distribution of resources and enabling conflict resolution. Taken together, these theoretical reviews suggest that team power dispersion, or hierarchy, should predominantly benefit team performance. However, while much research in social psychology and organizational behavior focuses on the benefits of hierarchy, or power dispersion, research in sociology, political science, and international relations notes that hierarchies, or differences in resources, are an important source of perceived inequalities, conflicts, and even wars (for example, Muller, 1985). When some members have more resources than others, this can breed jealously, rivalry, power struggles, and conflicts. This line of thought suggests that low AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 97 30/04/2014 14:55 98 Handbook of conflict management research power dispersion, or power equality, best enhances the functioning of groups and collectives (Marx and Engels, 1848). Review of Empirical Findings on Team Power Dispersion Similar to the theoretical perspectives on this topic, empirical evidence on the benefits of hierarchy has been rather mixed. A handful of findings offer support for the theoretical benefits of hierarchy. Namely, power dispersion has been found to lead to more integrative agreements in the negotiation realm (Sondak and Bazerman, 1991), to promote peaceful relations in the chimpanzee realm (De Waal, 1982), to improve team performance via improved cooperation and coordination in professional basketball teams (Halevy et al., 2012), and, when manipulated, to reduce intrateam conflicts and improve team performance (Ronay et al., 2012). However, research does not always show positive effects of team power dispersion Research has also shown that negotiations end in more efficient, integrative agreements when power dispersion is minimized (for example, Mannix, 1993; McAlister et al., 1986; McClintock et al., 1973; Wolfe and McGinn, 2005). Relatedly, studies on professional baseball teams find that power dispersion in the form of intrateam pay differences reduces team performance (Bloom, 1999; DeBrock et al., 2004; Depken, 2000; Jewell and Molina, 2004; Richards and Guell, 1998). In an attempt to compare these findings across different sports leagues (baseball, basketball, American football, and ice hockey), Frick et al. (2003) show that a higher degree of pay inequality enhances the performance of basketball and ice hockey teams but harms the performance of American football and baseball teams. Therefore, both positive and negative findings exist on the effects of power dispersion in teams. To reconcile these divergent sets of findings, Halevy et al. (2012) propose that power dispersion is useful for interdependent tasks where members rely on one another to complete the task, such as in basketball, but is unnecessary on tasks where members do not need to cooperate closely and have more independent roles, such as baseball or football. In support of this reasoning, Ronay et al. (2012) indeed find that power dispersion is beneficial for team performance when procedural interdependence is high, but not when interdependence is low. This therefore offers an interesting potential explanation of when power dispersion may help rather than hurt team performance. However, while this provides a potentially interesting explanation for the context-­ contingent effects of hierarchy, not all studies support this line of thought. For example, some studies have simply found no effect of power dispersion in interdependent basketball teams (Berri and Jewell, 2004) or in independent baseball teams (Gomez, 2002), and other studies have even found effects the opposite of what this reasoning would predict. Sommers (1998) finds a negative effect of hierarchy in interdependent ice hockey teams, and Franck and Nuesch (2011) find in a study of highly interdependent professional German soccer teams that there is a curvilinear effect of pay dispersion, or hierarchy, on team performance, showing that teams perform best when moderate levels of power dispersion exist. One explanation for why past findings are rather mixed, and even moderator theories have received inconsistent support, is that examinations of power dispersion often confound power dispersion with power level. Teams with high power dispersion have AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 98 30/04/2014 14:55 Power in teams ­99 moderate levels of team power, and teams with low power dispersion have either a similarly high or low power level. This means that it is hard to know if having a moderate amount of power drives the benefits of dispersion, or if dispersion itself does. Indeed, past research has shown that moderate levels of team power yield maximum team performance (Groysberg et al., 2010). Additionally, past contradictory findings on dispersion may be because for low dispersion, researchers often lump together both low-­ and high-­power teams, which can markedly differ from one another, creating noise in the comparison between low-­ and high-­power dispersion. This confound between the two types of power structures may explain some of the discrepant findings in the above-­ mentioned studies. In an attempt at removing the confusion between power level and power dispersion, Greer and Van Kleef (2010) examined level and dispersion separately, in a field and a lab study. When controlling for the effects of power level, they did not find an effect of power dispersion or hierarchy on team conflict resolution. However, they did find that the interaction between power level and power dispersion predicted team functioning. Their findings revealed that hierarchy was useful for teams with low power, but problematic in teams with high power. In low-­power teams, a lack of hierarchy created a power vacuum, which gave rise to power struggles that impeded cooperation and conflict resolution within the team. In contrast, in high-­power teams, members preferred a balance of power (no hierarchy). Because when members have high power they all value power, and are more prone than low-­power team members to be sensitive to jealousy, threat, and status contests when power differences exist within the team. Together, the emerging body of work on the role of hierarchy in teams suggests that both benefits and detriments of hierarchy, or team power dispersion, exist. On the upside, team power dispersion can improve cooperation, coordination, and role clarity, but on the downside, it can breed feelings of inequality and resentment. Whether the benefits or detriments of hierarchy arise depend largely on the context, including the interdependence of the task or the mean level of power of the team. TEAM POWER VARIETY In addition to looking at the level and dispersion of power held by members within the team, researchers have also begun to look at differences in the type of power held by team members, or team power variety. Members’ power, or position in a team hierarchy, can be drawn from multiple sources (Halevy et al., 2011; Morgeson et al., 2010), such as legitimate authority or expertise (French and Raven, 1959) or personal characteristics such as functional background or gender (Berger et al., 1972). Team power variety is defined here, in line with past research (Greer et al., 2011b), as the degree to which members vary from one another in the source(s) from which they draw their power and influence within a team. When team power variety is high, team members draw their relative and varying levels of power from different sources. This is likely to reduce power struggles and conflicts between team members because it increases role clarity and reduces the potential for social comparisons and jealousy over a common power source. Greer et al. (2011b) reason that when members have fundamentally different forms of power, members can AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 99 30/04/2014 14:55 100 Handbook of conflict management research not directly or easily compare their relative power levels to one another, as power in one domain (that is, legitimate authority) may be fundamentally different than power held in another domain (that is, expertise). When members are unable to easily compare their basis of power to that of their other team members, this reduces negative social comparisons within the team, feelings such as envy, and resultant conflicts about status and power (Bendersky and Hays, 2012; Greer and van Kleef, 2010). Additionally, having different power sources gives members information about their roles in the teams, providing role clarity and facilitating cooperation and coordination. Therefore, this line of theory suggests that team power variety should be beneficial for team functioning. However, at the same time, when members draw their power from different sources, this may also create problems. This type of diversity may imply that members have different thought worlds, which can impair team communication and performance (Dougherty, 1992). Additionally, members may identify more with their individual power source rather than the team as whole, creating dividing lines and subgroups based on the different power sources available in the team. In such situations intersubgroup conflicts may emerge, which detract from team functioning (compare with Lau and Murnighan, 1998). Therefore, team power variety also has the potential to harm team outcomes. Review of Empirical Findings on Team Power Variety The empirical studies of power variety to date offer primary support for the positive perspective on team power variety. For example, Greer et al. (2011b) show that power variety, operationalized as the degree to which team members differ in their primary base of power within the team, reduces team-­power struggles and improves team performance. Additionally, they find that it also moderates the effects of team power level, such that in teams with a high-­power level, team power variety reduces the negative effects of team power level, and allows high-­power teams to perform to their full capacity. Similarly, Groysberg et al. (2011) find that team power variety moderates the effects of team power level. Specifically, they find that the problem of having too many star employees in a team is particularly problematic when the stars came from a small number of sectors, suggesting issues with overlapping expertise among these high-­power employees that could be remedied if members’ power came from more varied sources. Together, both these studies suggest that team power variety can help clarify member roles and alleviate power struggles, thereby improving team performance. POTENTIAL MODERATORS OF TEAM POWER STRUCTURES This review highlights that discrepant findings on the role of power structures in teams exist, particularly in regard to power level and dispersion. Therefore, understanding potential moderators of the effects of team power structures is critical. Firstly, different aspects of the power structures themselves may interact to determine the ultimate profile of power in teams. For example, as mentioned above, power dispersion and variety may moderate the effects of power level. Teams with high power levels perform best when power dispersion is low (Greer and Van Kleef, 2010) and power variety is high (Greer AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 100 30/04/2014 14:55 Power in teams ­101 et al., 2011b; Groysberg et al., 2010). This is because when members in a team all have high levels of power, they are very competitive. Removing the basis for this (such as the inequities present under high power dispersion, or the possibility for comparison and jealousy over the same power bases) can alleviate the problems in teams with high power levels. Additionally, one could also speculate that team power variety reduces the potential negative sides of team power dispersion. When controlled resources differ, and the potential for comparisons and jealousy are reduced, the potential inequalities and power struggles that can arise in teams with high power dispersion should also be reduced. Secondly, another category of moderators of the effects of team power structures is based in the key mechanism by which power has its effects – perception. How members perceive the power of themselves and their teammates may have important consequences for the effectiveness of the power structure in the team. Two key aspects of power perception in teams that may moderate the effects of team power structures are congruency and legitimacy. Firstly, team power structure congruency is defined as the degree to which team members agree with one another about the relative rank-­ordering of themselves and others within the team (Greer et al., 2011b; based on the notion of interpersonal congruence, Polzer et al., 2002). Secondly, team power structure legitimacy is defined as the degree to which team members believe the power structure in the team is fair and justified (based on Lammers et al., 2008; Tyler, 2006). Of note is that, while the effects of legitimacy are likely to be exacerbated when all team members believe in the hierarchy, it could take as little as one team member who believes in the legitimacy of the hierarchy to persuade others to accept it. Legitimacy should be understood as a compilation construct, which could be operationalized as an individual-­level construct, or the average of individual perceptions of legitimacy to the team level, or the score of the highest or lowest scoring member. Congruency of Member Perceptions of Team Power Structure A key moderator of the effects of team power structures is likely to be congruency, or the degree to which members agree on the place of themselves and others in the team power structure. While team members often agree with one another on the nature of the power structure in the team, situations exist in which members’ perceptions may vary. Power, and its perception, is often dynamic, and as such perceptions of individual power positions within the group may conflict (Owens and Sutton, 2001). When individuals disagree about the power structure, structures in the team (all forms) are more likely to give rise to conflicts. For example, Anderson and colleagues (2006, 2008) have shown that when a team member overestimates their intragroup power, other members are likely to reject and even punish them. In contrast, when individuals in the team agree about the power structure, this power congruence has been shown to minimize the relationship between team power level and intragroup conflict (Greer et al., 2011b). Therefore, initial support shows that congruent power perceptions may improve the effects of team power level. Future research on the moderating effects of team power congruency on other power structures, such as dispersion and variety, would be interesting. Additionally, whether the member(s) with incongruent perceptions of the power structure in the team are low-­power or high-­power team members may be of importance. For example, low-­ power holders who overstep their place in the team may be more severely punished by AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 101 30/04/2014 14:55 102 Handbook of conflict management research those with high power, while high-­power holders with inflated perceptions of their place in the team could be reprimanded by those with low power. Legitimacy of Team Power Structure The second perceptual moderator of the effects of team power structures is perceived legitimacy, or the degree to which members perceive a power structure (level, dispersion, or variety) to be fair and justified. Perceived legitimacy of power structure is likely to reduce the negative effects of all power structures and improve the positive effects. This is because when members believe that the structure is legitimate, they are less likely to act against or engage in power struggles. Halevy et al. (2011), in their theoretical paper on the benefits of hierarchy, explain that legitimacy facilitates cooperation, decreases conflict and friction between team members, stabilizes the power structure, and motivates individual members. This leads to the conclusion that legitimacy may be an important moderator of team power structures, bringing out benefits such as cooperation and coordination, and minimizing conflicts. However, until this point, no research has explicitly examined the role of legitimacy in moderating the effects of team-­level power structures. Investigation of such effects would be an interesting pathway for future research. DISCUSSION Team power structures have important implications for team functioning. At the start of this chapter, the question was posed whether a team of power-­hungry Napoleons would conquer the world or fall prey to power struggles and implode. As seen in this review of the literature to date on power structures in teams, it appears that out of the different power structures possible, high team power level particularly appears to incite high levels of conflict and decreased team functioning. When multiple high-­power team members – multiple Napoleans – have to work together, egos and power concerns take over, and power struggles ensue (Greer and Van Kleef, 2010). Such power struggles can give rise to intragroup conflicts, impede team conflict resolution, and harm team functioning (compare with Greer et al., 2011). Therefore, a team with only a single high-­power member and then several other lower power members might fare better than a team populated only by high-­power members, or Napoleons. Indeed, much theorizing on the role of power dispersion and hierarchy suggests that such a hierarchically differentiated team structure would allow for optimal team functioning (for example, Halevy et al., 2011; Keltner et al., 2008). However, empirical findings to date suggest that creating hierarchy in teams does not unequivocally lead to improved team outcomes. Rather, power dispersion or hierarchy may only benefit team functioning at moderate levels of team power dispersion (Franck and Nuesch, 2011), when teams have mean low levels of power (Greer and Van Kleef, 2010) or high levels of interdependence (Ronay et al., 2012), or when members have congruent perceptions of the hierarchy and its legitimacy (compare with Halevy et al., 2011). Therefore, while a team with a single Napoleon has more chance to succeed than a team full of Napoleons, certain conditions may improve or worsen the effects of both of these types of team power structures. AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 102 30/04/2014 14:55 Power in teams ­103 Lastly, instead of creating a team full of Napoleons or a team composed of one Napoleon and several followers, a team could also be created in which all of the Napoleons have a different source of power (one would have the most prowess in public speaking, another in battle plans, a third in combat skills). Such a team of high-­power members, where each of their power comes from a different source, might have a greater chance of success. Research so far supports this idea that variety in member power base can lead to positive outcomes, and that particularly the interaction of team power variety and power level can lead to the highest levels of team functioning. Therefore, to answer the question posed at the start of this chapter, a team composed of high-­power leaders who all draw their power from different sources might have the best chance of conquering the world without dissolving into power struggles and conflict. In sum, there is a growing understanding of the nature of different team power structures, and the power structures needed for optimal team functioning across different contexts. Team power level is generally negative, but has the potential for positive outcomes when the power variety or power congruence is high. Team power dispersion or hierarchy has shown largely mixed effects on team outcomes. By taking into account team power level and team interdependence, positive and negative effects of team power dispersion can be more reliably predicted. Specifically, team power dispersion is most useful when the power level is low and team interdependence is high. In that sense, power dispersion would be an optimal power structure for factory-­line teams, for example, which have high interdependence and low power levels. Lastly, initial studies on team power variety suggest that when members control different bases of power, this is generally positive for team functioning. Additionally, team power variety can improve the effects of other power structures, including bringing out the benefits of both power level and dispersion by increasing role clarity and decreasing the relevance of social comparisons and perceived inequalities. FUTURE DIRECTIONS An important direction for future research on power and teams is understanding the dynamics processes set into play by different types of team power structures. As Malholtra and Gino (2012, p. 560) note, “little has been done to evaluate whether and how the pursuit of power itself shapes both intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics.” At this point, scant theory and research speaks to the evolution of these power processes over time, and to how team power structures shape team behavioral interactions to ultimately determine performance. One potentially key dynamic process to understand in relation to team power structures and outcomes is team power struggles. Such struggles are defined as competition over the control of valued resources within the team (Greer and Van Kleef, 2010). While initial research suggests that intrateam power struggles, or related status conflicts, are generally negative for team functioning, including impairing effective conflict resolution (Greer and Van Kleef, 2010) and team performance (Bendersky and Hays, 2012; Greer et al., 2011), the possibility exists that such power struggles may also have the capacity to improve team functioning. This may depend, for example, on the manner in which team members engage in power AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 103 30/04/2014 14:55 104 Handbook of conflict management research struggles. While this has yet to be extensively documented, research in other traditions has identified certain behaviors individuals employ to gain leadership. For example, Martorana et al. (2005) suggest that those overthrowing a hierarchy may engage in four types of actions: (1) over, non-­normative actions, such as overt sabotage, terrorism, and strikes; (2) covert, non-­normative action, such as covert sabotage, reductions in effort (social loafing), and hidden transcripts (gossip); (3) overt, normative action, such as formally sanctioned strikes or statements at open meetings; and (4) normative covert behavior, such as obeying rules to paralyze work. While this paints a fairly bleak picture of power struggles, other research has shown that individuals wishing to rise to power can do so on the basis of their charisma or expertise (French and Raven, 1959). Therefore, as opposed to trying to destroy the power of others, individuals could simply try to outperform their rivals as a way of gaining power in the group. In such situations where members strive for power with positive influence behaviors, power struggles might even benefit group functioning. Whether power struggles benefit individual functioning also remain a question – while it could be hypothesized that if individuals engage in more positive power struggle behaviors, such as increased effort, their performance should go up. Initial research by Bendersky and Shah (2012) suggests that to gain status in groups over time, individuals may actually suffer performance deficits, perhaps because they traded off resources that would have been valuable for their own performance to gain status in the team. They find, for example, that generosity predicts individual status gains. Whether these effects also generalize to gaining power, or increased resource control, in the group would be interesting to future research. One could speculate that the mechanisms by which one gains resources may be different than the resources by which one acquires respect. Another important direction for future research is further identification of the moderators of the effects of different team power structures. Here team power congruency and legitimacy are proposed to moderate the effects of team power structure on outcomes. However, other moderators are likely to exist. For example, task type may be important. Team power level, whose benefits involve member voice and participation, may only be beneficial for non-­routine or complex tasks, where information exchange and elaboration is critical. Organizational context may also be an important moderator. For example, during a crisis, the coordination benefits of power dispersion may outweigh potential conflicts over inequalities, allowing power dispersion to be more positive for team performance when the team is in a high-­pressure crisis situation that demands efficient coordinated action. PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS Power has an enormous influence on teams. Understanding how to create and manage appropriate team power structures is a vital skill for managers. For example, high-­power teams, from top management teams to task forces of world leaders, have an enormous impact on society. Their performance (the quality of their decisions, the creativity of their solutions, and so on) can determine the performance of the entire system that they lead – their organization, their country, the world. However, these teams are often ineffective AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 104 30/04/2014 14:55 Power in teams ­105 and do not perform to the best of their capabilities. By understanding the nature of team power structures as this, managers may be able to help these teams perform better. For example, managerial solutions for the problems of high-­power teams would include job designs which involve non-­overlapping responsibilities and power bases between high-­ power members (to reduce competition over the same power base, and therefore threat and conflict) or team trainings to promote congruent power perceptions within the team. CONCLUSION Team power structures – power level, power dispersion, and power variety – can have important repercussions for team conflicts and outcomes. Understanding the effects of these different types of power structures is critical for the effective management of organizational teams. NOTES 1.As Harrison and Klein (2007) note, another central type of team composition is separation. This chapter focuses on power structures in terms of level, variety, and dispersion, as the bulk of research so far has been on these topics. 2. While these three dimensions of power structures in teams may have some relation to one another (that is, there is more room for power dispersion when teams have moderate, rather than high or low average levels of power), all three forms also may exist independently of one another (that is, both high-­and low-­power teams may have high or low power dispersion and variety). REFERENCES Anderson, C., Ames, D. R., and Gosling, S. D. (2008). Punishing hubris: The perils of overestimating one’s status in a group. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 90–101. Anderson, C., and Galinsky, A. D. (2006). Power, optimism, and risk-­taking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 511–36. Anderson, C., Srivastava, S., Beer, J. S., Spataro, S. E., and Chatman, J. A. (2006). Knowing your place: Self-­ perceptions of status in face-­to-­face groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 1094–110. Bendersky, C., and Hays, N. A. (2012). Status conflict in groups. Organization Science, 23, 323–40. Bendersky, C., and Shah, N. P. (2012). The cost of status enhancement: Performance effects of individuals’ status mobility in task groups. Organization Science, 23, 308–22. Berger, J., Cohen, B. R., and Zelditch, M. Jr. (1972). Status characteristics and social interaction. American Sociological Review, 37, 241–55. Berri, D. J., and Jewell, T. R. (2004). Wage inequality and firm performance: Professional basketball’s natural experiment. Atlantic Economic Journal, 32, 130–39. Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books. Bloom, M. (1999). The performance effects of pay dispersion on individuals and organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 25–40. Bonaparte, N. (1804/2014). Available at: http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/n/napoleonbo165317. html. Accessed March 1, 2014. Bruins, J. J., and Wilke, H. A. M. (1992). Cognitions and behavior in a hierarchy: Mulder’s power theory revisited. European Journal of Social Psychology, 22, 21–39. Campion, M. A., Medsker, G. J., and Higgs, A. C. (1993). Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: Implications for designing effective work groups. Personnel Psychology, 46, 823–50. Carson, J. B., Tesluk, P. E., and Marrone, J. A. (2007). Shared leadership in teams: An investigation of antecedent conditions and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1217–34. AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 105 30/04/2014 14:55 106 Handbook of conflict management research Chattopadhyay, P., Finn, C., and Ashkanasy, N. M. (2010). Affective responses to professional dissimilarity: A matter of status. Academy of Management Journal, 53(4), 808–26. De Cremer, D., and Van Dijk, E. (2005). When and why leaders put themselves first: Leader behavior in resource allocations as a function of feeling entitled. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 553–63. De Dreu, C. K. W., Giebels, E., and Van de Vliert, E. (1998). Social motives and trust in integrative negotiation: The disruptive effects of punitive capability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 408–22. De Dreu, C. K. W., and West, M. A. (2001). Minority dissent and team innnovation: The importance of participation in decision-­making. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 1191–201. De Waal, F. (1982). Chimpanzee Politics: Sex and Power Among Apes. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. DeBrock, L., Hendricks, W., and Koenker, R. (2004). Pay and performance: The impact of salary distribution on firm-­level outcomes in baseball. Journal of Sports Economics, 5, 243–61 Depken, C. A. (2000). Wage disparity and team productivity: Evidence from Major League Baseball. Economic Letters, 67, 87–92. DeRue, D. S., and Ashford, S. J. (2010). Who will lead and who will follow? A social process of leadership identity construction in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 35, 627–47. Dougherty, D. (1992). Interpretive barriers to successful product innovation in large firms. Organization Science, 3, 179–202. Ebenbach, D. H., and Keltner, D. (1998). Power, emotion, and judgmental accuracy in social conflict: motivating the cognitive miser. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 20, 7–21. Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–83. Elangovan, A. R., and Xie, J. L. (1999). Effects of perceived power of supervisor on subordinate stress and motivation: The moderating role of subordinate characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 359–73. Ellemers, N. (1993). The influence of socio-­structural variables on identity-­management strategies. European Review of Social Psychology, 4, 27–57. Emerson, R. M. (1962). Power-­dependence relations. American Sociological Review, 27(1), 31–41. Fiol, C. (1994). Consensus, diversity, and learning in organizations. Organization Science, 5, 403–20. Fiske, S. T., and Berdahl, J. (2007). Social power. In A. Kruglanski and E. T. Higgins (eds), Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, 2nd edition, New York: Guilford, pp. 678–92. Franck, E., and Nuesh, S. (2011). The effect of wage dispersion on team outcome and the way team outcome is produced. Applied Economics, 43(23), 3037–49. French, J., and Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (ed.), Studies in Social Power, Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, pp. 150–67. Frick, B., Prinz, J., and Winkelmann, K. (2003). Pay inequalities and team performance. Empirical evidence from the North American major leagues. International Journal of Manpower, 24, 472–88. Georgesen, J., and Harris, M. J. (2006). Holding onto power: Effects of powerholders’ positional instability and expectancies on interactions with subordinates. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 451–68. Giebels, E., De Dreu, C. K. W., and Van de Vliert, E. (2000). Interdependence in negotiation: Impact of exit options and social motives on distributive and integrative negotiation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30, 255–72. Gomez, R. (2002). Salary compression and team performance: evidence from the National Hockey League. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft, 72, 203–20. Greer, L. L., Caruso, H. M., and Jehn, K. A. (2011). The bigger they are, the harder they fall: Linking team power, conflict, congruence, and team performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 116, 116–28. Greer, L. L., de Hoogh, A. H. B., Patel, P., and Thatcher, S. M. B. (2011). When leaders struggle for power: The dark side of shared leadership. Academy of Management Annual Meeting, San Antonio, Texas. Greer, L. L., and Van Kleef, G. A. (2010). Equality versus differentiation: The effects of power dispersion on social interaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 1032–44. Groysberg, B., Polzer, J. T., and Elfenbein, H. (2011). Too many cooks spoil the broth: How high-­status individuals decrease group effectiveness. Organization Science, 22, 722–37. Guinote, A. (2007). Behaviour variability and the situated focus theory of power. European Review of Social Psychology, 18, 256–95. Halevy, N., Chou, E. Y., and Galinsky, A. D. (2011). A functional model of hierarchy: Why, how, and when vertical differentiation enhances group performance. Organizational Psychology Review, 1, 32–52. Halevy, N., Chou, E., Galinsky, A., and Murnighan, J. K. (2012). When hierarchy wins: Evidence from the National Basketball Association. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 398–406. Harrison, D. A., and Klein, K. J. (2007). What’s the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32, 1199–228. AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 106 30/04/2014 14:55 Power in teams ­107 Isen, A. M., and Geva, N. (1987). The influence of positive affect on acceptable levels of risk: The person with a large canoe has a large worry. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Making Process, 39, 145–54. Jewell, R. T., and Molina, D. J. (2004). Productive efficiency and salary distribution: The case of US Major League Baseball. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 51, 127–42. Katz, D., and Kahn, R. L. (1978). The Social Psychology of Organizations, 2nd edition, New York: Wiley. Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., and Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110, 265–84. Keltner, D., Van Kleef, G. A., Chen, S., and Kraus, M. W. (2008). A reciprocal influence model of social power: Emerging principles and lines of inquiry. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 151–92. King, N., Anderson, N., and West, M. A. (1992). Organizational innovation: A case study of perceptions and processes. Work and Stress, 5, 331–39. Klein, K. J., Ziegert, J. C., Knight, A. P., and Xiao, Y. (2006). Dynamic delegation: Shared, hiearchical, and deindividualized leadership in extreme action teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51, 590–621. Kwaadsteniet, E. W., and van Dijk, E. (2010). Social status as a cue for tacit coordination. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 515–24. Lammers, J., Galinsky, A. D., Gordijn, E. H., and Otten, S. (2008). Illegitimacy moderates the effects of power on approach. Psychological Science, 19, 558–64. Lammers, J., Stoker, J. I., and Stapel, D. A. (2009). Differentiating social and personal power: Opposite effects on stereotyping, but parallel effects on behavioral approach tendencies. Psychological Science, 20, 1543–49. Lau, D., and Murnighan, J. K. (1998). Demographic diversity and faultlines: The compositional dynamics of organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, 23, 325–40. Magee, J. C., and Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Social hierarchy: The self-­reinforcing nature of power and status. Academy of Management Annals, 2, 351–98. Malhotra, D., and Gino, F. (2011). The pursuit of power corrupts: How investing in outside options motivates opportunism in relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly, 56, 559–92. Maner, J. K., Gailliot, M. T., Butz, D. A., and Peruche, B. M. (2007). Power, risk, and the status quo: Does power promote riskier or more conservative decision making? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 451–62. Mannix, E. A. (1993). Organizations as resource dilemmas: The effects of power balance on coalition formation in small groups. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 55, 1–22. Mannix, E. A., and Sauer, S. J. (2006). Status and power in organizational group research: Acknowledging the pervasiveness of hierarchy. In E. Lawler and S. Thye (eds), Advances in Group Processes: Social Psychology of the Workplace, vol. 23, New York: Elsevier, pp. 149–82. Marx, K. H., and Engels, F. (1848/1967). The Communist Manifesto. Trans. AJP Taylor. London: Penguin. Maslow, A. (1937). Dominance-­feeling, behavior and status. Psychological Review, 44, 404–29. McAllister, L., Bazerman, M. L., and Faber, P. (1986). Power and goal setting in channel negotiations. Journal of Marketing Research, 23, 238–63. McClintock, C., Messick, D., Kuhlman, D., and Campos, F. (1973). Motivational bases of choice in three-­ person decomposed games. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9, 572–90. Morgeson, F. P., DeRue, D. S., and Karam, E. P. (2010). Leadership in teams: A functional approach to understanding leadership structures and processes. Journal of Management, 36(1), 5–39. Mulder, M. (1977). The Daily Power Game. Leiden, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff. Muller, E. N. (1985). Income inequality, regime repressiveness, and political violence. American Sociological Review, 50(1), 47–61. Mumford, M. D., and Gustafson, S. B. (1988). Creativity syndrome: Integration, application, and innovation. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 27–43. Owens, D. A., and Sutton, R. I. (2001). Status contests in meetings: Negotiating the informal order. In M. Turner (ed.), Groups at Work: Advances in Theory and Research, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 299–316. Pearce, C. L., and Sims, H. P. (2002). The relative influence of vertical vs. shared leadership on the longitudinal effectiveness of change management teams. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 6(2), 172–97. Pfeffer, J., and Salancik, G. R. (1978). The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. New York: Harper and Row. Polzer, J. T., Milton, L. P., and Swann, W. B. (2002). Capitalizing on diversity: Interpersonal congruence in small groups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 296–324. Porath, C. L., Overbeck, J. R., and Pearson, C. M. (2008). Picking up the gauntlet: How individuals respond to status challenges. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(7), 1945–80. Richards, D. G., and Guell, R. C. (1998). Baseball success and the structure of salaries. Applied Economics Letters, 5, 291–96. AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 107 30/04/2014 14:55 108 Handbook of conflict management research Ronay, R., Greenaway, K., Anicich, E. M., and Galinsky, A. D. (2012). The path to glory is paved with hierarchy when hierarchical differentiation increases group effectiveness. Psychological Science, 23(6), 669–77. Rubin, J. Z., and Brown, R. (1975). The Social Psychology of Bargaining and Negotiation. New York: Academic Press. Sassenberg, K., Jonas, K. J., Shah, J. Y., and Brazy, P. C. (2007). Why some groups just feel better: The regulatory fit of group power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 249–67. Scheepers, D., and Ellemers, N. (2005). When the pressure is up: The assessment of social identity threat in low and high status groups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 192–200. Schweiger, D., Sandbert, W., and Rechner, P. (1989). Experiential effects of dialectical inquiry, devil’s advocacy, and consensus approaches to strategic decision making. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 745–72. Smith, P. K., and Trope, Y. (2006). You focus on the forest when you’re in charge of the trees: Power priming and abstract information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 578–96. Smith-­Lovin, L., and Brody, C. (1989). Interruptions in group discussions: The effects of gender and group composition. American Sociological Review, 54, 424–35. Sommers, P. M. (1998). Work incentives and salary distributions in the National Hockey League. Atlantic Economic Journal, 26, 119. Sondak, H., and Bazerman, M. H. (1991). Power balance and the rationality of outcomes in matching markets. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 1–23. Stasser, G., and Titus, W. (1987). Effects of information load and percentage of shared information on the dissemination of unshared information during group discussion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 81–93. Tetlock, P. E. (2002). Social functionalist frameworks for judgment and choice: Intuitive politicians, theologians, and prosecutors. Psychological Review, 109(3), 451. Thibaut, J. W., and Kelley, H. H. (1959). The Social Psychology of Groups. Oxford, UK: Wiley. Thibaut, J. W., and Walker, L. (1975). Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 375–400. Wolfe, R. J., and McGinn, K. L. (2005). Perceived relative power and its influence on negotiations. Group Decision and Negotiation, 14, 3–20. AYOKO 978178100693 1 PRINT (M3428) (G).indd 108 30/04/2014 14:55