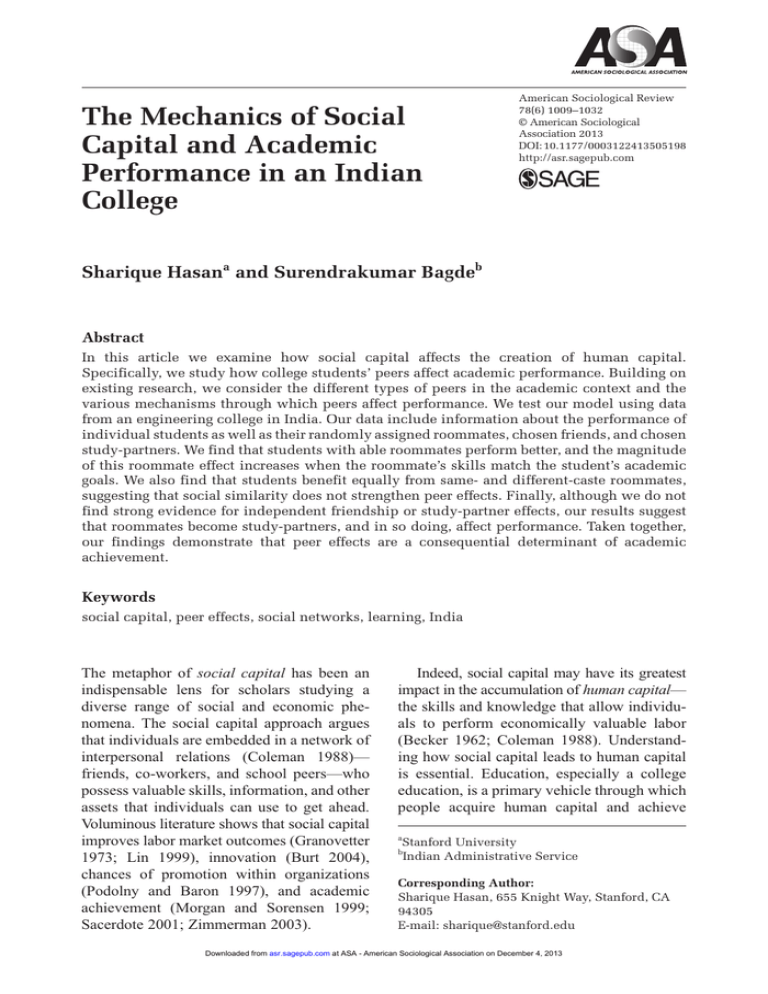

The Mechanics of Social Capital and Academic 505198

advertisement