A REVIEW OF THE THEORY OF OPTIMUM CURRENCY AREAS By

advertisement

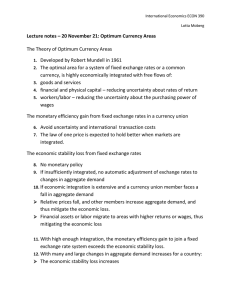

A REVIEW OF THE THEORY OF OPTIMUM CURRENCY AREAS - IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FUTURE OF THE EUROZONE By Joseph G Nellis Professor of International Management Economics Cranfield School of Management 1. Background Research into the nature of and implications arising from the establishment of an optimum currency area (OCA) has been ongoing since the pioneering work by Mundell (1961) and McKinnon (1963). The topic has increased in significance in more recent years, particularly within the European Union, as a result of the formation of euroland (or eurozone) on 1 January 1999 (membership increased to twelve on 1 January 2001 when Greece joined; at the time of writing, there are 17 members in the eurozone). A heated debate has been ongoing concerning the consequences of deeper European integration and the economic costs and benefits of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) involving the creation of the single European currency, the euro. This Review Paper on the theory of optimum currency areas provides a background to this debate – a debate that some observers have suggested has so far largely been centred on political dogma – and will hopefully serve as a foundation for a more academically-based assessment. The topic has also grown in significance in the context of the sovereign debt crisis which has rocked a number of European states in recent years. The scale of the crisis has led to speculation about the very survival of the euro currency itself and the future pace of European integration (including not only monetary union but also fiscal harmonisation – and, perhaps, ultimately political union). Suggestions have been raised that it might be wiser for members to pause and consider forming a “two-speed” eurozone with the strongest countries forging ahead with ever-closer integration and the others taking a longer timescale to adjust. Section 2 below defines the meaning of an optimum currency area and reviews the arguments concerning flexible versus fixed exchange rate regimes. The properties of an OCA are reviewed in Section 3 based on price and wage flexibility as well as the degree of integration between regions. The costs and benefits derived from participation in an OCA are set out in Section 4 while recent developments in research in this area and conclusions are brought together in the final section along with some brief thoughts about the future of the euro. 1 2. Definition of an Optimum Currency Area An optimum currency area refers to the ‘optimum’ geographical size within which the general means of payments is: either a single common currency (as in the case of the euro) or a group of currencies whose exchange values are irrevocably pegged to one another with unlimited convertibility for both current and capital account transactions on the balance of payments, but whose exchange rates fluctuate in unison against the major currencies from the rest of the world. In this context, the idea of an ‘optimum’ is defined in macroeconomic terms with respect to the maintenance of so-called internal and external balance. Internal balance is achieved at the optimal trade-off point between inflation and unemployment – consistent with zero (or non-accelerating inflation) and a rate of unemployment which is “voluntary” in the sense that the only people unemployed are those who are unwilling to work at the going wage rate (defined as classical unemployment). This trade-off is appropriately illustrated with reference to the Phillips curve (for details, see Phillips, 1958). External balance is concerned with the maintenance of sustainable balance of payments positions (i.e. the absence of persistent current account deficits or surpluses). The concept of OCAs was originally developed in the 1950s and early 1960s in the context of research and analysis concerning the relative merits of fixed versus flexible exchange rate regimes. There have been many early supporters of flexible exchange rates, most notably Milton Friedman (1953), who argued that a country experiencing price and wage rigidities should adopt flexible exchange rates in order to maintain both internal and external balance. Under a system of fixed exchange rates with price and wage rigidities, any effort by policy makers to correct international payments imbalances would result in unemployment (arising from an over-valued currency and a consequent loss of international competitiveness) or inflation (arising from an under-valued currency leading to rising import prices). In contrast, under flexible exchange rates the induced changes in relative prices and real wages (and hence international competitiveness) would, in the longrun, eliminate international payments imbalances without much of the burden of real adjustment, in particular, on employment levels. Such an argument in favour of flexible exchange rates provides support for the view that a country should adopt a flexible exchange rate regime irrespective of its fundamental economic characteristics, since market forces will ensure continuous adjustment towards internal and external balances. The main problem with Friedman’s logic concerning flexible exchange rates is that it fails to recognise that countries fundamentally differ in so many ways – for example, in terms of endowments of natural resources, productivity levels, capital-labour ratios, skill levels etc. Given such differences, the theory of 2 optimum currency areas claims that, if a country is sufficiently highly integrated with the “outside world” in terms of financial transactions, financial mobility or commodity trading, then a fixed exchange rate regime (or, in the extreme, a single currency) may be more effective and more efficient in reconciling internal and external balances than a system of flexible exchange rates. This is the core of the argument put forward in recent years by supporters of the euro, although a question remains concerning the extent to which the degree of integration that has so far been achieved between the current 17 members of the European Union is sufficient to provide an appropriate foundation for the creation of a successful OCA, let alone a single common currency. Supporters of the euro argue that integration is a dynamic and ongoing process – and that criticism against the euro is, therefore inappropriate (and, in some cases, based on nationalistic tendencies on the part of some countries from outside the area). However, the recent “euro crisis” has put the spotlight on those countries in the eurozone that have failed to ensure appropriate structural and sustainable adjustments enabling them to remain competitive and attractive to investors within the single currency area. As noted above, the pioneers of research into OCAs were Mundell (1961) and McKinnon (1963). The focus of their research was an attempt to identify the most fundamental economic properties required to define an ‘optimum’ currency area. In this context, recognition should also be given to the parallel contribution by Ingram (1962). Later research by a number of others including Grubel (1970), Corden (1972), Ishiyama (1975) and Tower and Willet (1976) moved the attention away from the required fundamental properties of an OCA to an evaluation of the costs and benefits which stem from OCA participation. Hamada (1985) later studied the implications of an individual country’s decision to participate in an OCA from the standpoint of social welfare. The following sections provide a review of some of this subsequent research. 3. Properties of an Optimum Currency Area The research into OCAs has led to the generally accepted conclusion that a successful (i.e. sustainable) OCA requires five specific conditions to be met. These conditions are concerned with the degree of: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Price and wage flexibility Financial market integration Factor market integration Goods market integration Macroeconomic policy co-ordination and political integration Conditions 2, 3 and 4 lie at the heart of the Single European Market programme, instigated by the European Commission in 1986 to provide the basis for the free flow of goods, services, people and capital. Completion of this programme was, therefore, an essential prerequisite for the launch of the euro project. We comment on each of these conditions in turn. 3 3.1 Price and Wage Flexibility The extent to which price and wage flexibility exists within a country has been at the heart of the debate surrounding the choice between fixed or flexible exchange rate regimes. Indeed, the assumed inflexibility of prices and wages was the basis for Friedman’s argument in favour of flexible exchange rates and the subsequent development of the optimum currency area literature (although it is also worth mentioning here that Friedman did not entirely dismiss the idea that a group of countries may fix their bilateral rates of currency exchange with each other and let the rates fluctuate jointly against the rest of the world – see Friedman 1953, p.193.) To explain and clarify the significance of price and wage flexibility, consider a geographical area made up of a group of regions (or countries). In this context, it can be postulated that if prices and (real) wages are sufficiently flexible throughout the wider area in response to changing conditions which affect demand and supply, the regions in the area should be tied together by a fixed exchange rate regime. Complete flexibility of prices and wages would ensure that market clearance is achieved everywhere and would also facilitate instantaneous real adjustment to disturbances affecting interregional payments without causing problems of growing unemployment and internal imbalance. The ultimate real adjustment consists of ‘a change in the allocation of productive resources and in the composition of the goods available for consumption and investment’ (Friedman, 1953 p.182). The required changes in relative prices and real wages accomplish such adjustment, so that the need for inter-regional (i.e., intra-area) exchange rate flexibility is avoided. Connecting the regions by a system of fixed exchange rates is beneficial to the area as a whole because it eliminates (currency exchange) transactions costs and stimulates competition arising from the “transparency” of prices. These are two of the key arguments which are put forward by supporters of the euro. External balance is simultaneously maintained by the joint floating of the area’s currencies against the rest of the world, thereby avoiding persistent deficits on the current and capital accounts, as well as by the greater degree of internal price-wage flexibility of the balance of payments. On the other hand, when prices and real wages are inflexible, the transition towards ultimate adjustment may be associated with rising and persistently high unemployment in one region and/or inflation in another. Some regions may even suffer from a combination of stagnation of output and high inflation – i.e. stagflation. This was the primary concern of commentators who initially opposed the adoption of the euro within the European Union – and recent developments within Europe have borne out many of their concerns, especially in countries such as Spain, Greece, Portugal and Ireland. In such situations, it is argued that exchange rate flexibility among the regions may partially assume the role of price-wage flexibility in the process of real adjustments to disturbances. To counterbalance this argument, greater degrees of internal financial, factor and goods market integration have been 4 proposed by a number of researchers as substitutes for exchange rate flexibility so as to warrant the establishment of an optimum currency area. This is the rationale for the call for greater fiscal harmonisation and ever closer economic integration between members of the eurozone by some commentators in recent times. 3.2 Financial Market Integration Ingram (1962) has focused on the extent to which a high degree of internal financial market integration can ensure a free flow of funds to finance interregional payments imbalances and ease the adjustment process within a region. It is argued that a successful common currency area must be tightly integrated with respect to financial markets if it is to be sustainable. When an inter-regional payments deficit is caused by a temporary but reversible disturbance, a free flow of capital can serve as a cushion to make the process back to internal and external balance real adjustment smaller and more manageable in terms of impact (or even unnecessary altogether). Though financial capital flows (apart from those induced by differentials in long-run real rates of return) cannot indefinitely sustain a deficit caused by a persistent and irreversible disturbance (the benefactors are unlikely to be willing to provide a bottomless pot of money to the beneficiaries), they allow real adjustment to be spread out over a longer period of time. The cost of adjustment is further minimised by the additional support derived from pricewage flexibility (noted above) and internal factor mobility (see 3.3 below), both of which tend to be higher in the longer run. In addition, financial transactions strengthen the long-term adjustment process through so-called wealth effects. These stem from the fact that surplus regions will be accumulating net claims and can therefore be expected to raise their total expenditures while deficit regions will be decumulating net claims and thus lowering their total expenditures. Both effects will support real adjustment towards a sustainable balance in all the regions of the optimum currency area – assuming that there is a willingness on the part of all regions to take the appropriate steps. It can thus be argued that financial market integration reduces the necessity for inter-regional (i.e. intra-area) terms-of-trade changes via exchange rate fluctuations, at least in the short-run. Considering the undesirable effects arising from exchange rate flexibility (such as excessive volatility in currency values combined with the negative impact on business confidence, capital flows and investment) and the associated exchange rate risk, fixed exchange rates may be preferred within the financially integrated area. The greater the degree of financial market integration, the stronger will be the case for the establishment of an OCA across the regions. Not surprisingly, a greater degree of financial market integration has, therefore, been a key objective of the euroland countries. However, the extent to which such integration has taken place in reality since the birth of the euro has been the subject of controversy and debate in the context of the recent European sovereign debt and financial crises. 5 3.3 Factor Market Integration Mundell (1961) has argued that an optimum currency area is defined by internal factor mobility (including both inter-regional and inter-industry mobility) and external factor immobility. Internal mobility of the factors of production (particularly labour) can help ease the pressure to alter real factor prices (e.g. wage rates) in response to disturbances affecting demand and supply – and thus the necessity for exchange rate movements as an instrument of adjustment of real factor price change can be avoided to some extent. In this sense factor mobility is a partial substitute for price-wage flexibility. This arises from the fact that the mobility of labour, for example, is not frictionless in the short-run (most workers do not pack-up and move house in search of new jobs or do not look for work in other sectors immediately after being made redundant). Therefore, it is more effective in easing the cost of long-run real adjustment to persistent payments imbalances than short-run adjustment to temporary imbalances, which is minimised by a greater degree of financial capital mobility and integration. Hence, factor market integration reduces the extent to which a fixed exchange rate regime interferes with the maintenance of sustainable interregional payments positions, while at the same time increasing the usefulness of money as a medium of exchange inside the optimum currency area. Internal balance (the optimum inflation-unemployment trade-off noted earlier) can be secured by the adoption of appropriate domestic monetary and fiscal policy measures, and external balance relative to the rest of the world can be accomplished by the joint floating of the exchange rates against the rest of the world (note, however, that membership of the euro means that each member country is unable to pursue an independent monetary policy and, in principle, has limited fiscal policy freedom as specified by the Maastricht Treaty). 3.4 Goods Market Integration The extent to which the USA has succeeded in achieving relative smoothness of longer-run inter-regional adjustment over a long period of time is often attributed to its high degree of internal openness. This suggests that a successful OCA area must have a free flow of goods and services, ensuring extensive cross-border trading inside the area. The extent to which trade is “free” to flow within a given area is often measured by such indicators as the ratio of tradeable to non-tradeable goods in production or consumption, the ratio of exports plus imports to gross domestic product, and the marginal propensity to import. McKinnon (1963) has raised the question of whether or not an area with a high degree of openness with respect to the free flow of trade should choose flexible exchange rates vis à vis other areas or unite with them to form a larger optimum currency area. This throws up a number of issues. First, suppose the area is externally highly open so that tradeables represent a large share of the goods produced and consumed. In this situation 6 exchange rate flexibility vis-à-vis other areas will not be effective in correcting unsustainable payments imbalances, since any exchange rate adjustment could be offset by price changes without any significant impact on the terms of trade or on real wages (the extent of this will vary from country to country depending on the causes of domestic inflationary pressures). It can be argued, therefore, that the area is too small and open for expenditureswitching instruments to have sufficient impact, though wealth effects operate in the direction of restoring external balance. The by-product is an unstable general price level across the area generally and widening inflation differentials between regions (as is currently the case in the eurozone). Under these circumstances, the area would find it more beneficial to adopt appropriate expenditure-switching policies (to reduce the demand for imports) in order to achieve external balance and to adopt a fixed exchange rate regime to support the aim of price stability, provided that the tradeable goods prices are stable in terms of the outside currency. Second, when the area is relatively closed against the rest of the world (as represented by a large share of total export and import trade taking place between members of the area itself), it should peg its currency to the body of non-tradeable goods and adopt a floating exchange rate regime to support the achievement of external balance. Exchange rate flexibility in this situation is effective because it brings about the desired changes in the relative price of tradeable goods and real wage adjustment. The conclusion from this discussion concerning goods market integration is that the optimal monetary arrangements of an internally open economy which is externally relatively closed would be to peg its currency (or currencies jointly) to the body of internally traded goods – which are viewed as nontradeables from the standpoint of the outside world – to achieve price stability, and to adopt externally flexible exchange rates for external balance. This, in general terms, describes the long-term view of prospects for the eurozone area economy. Splitting such an economy into smaller regions with independently floating exchange rates is not desirable, nor is attaching itself to the outside world to become part of a larger currency area (such as one based on a US$ standard). This raises the question as to whether or not the UK should continue to float sterling against the euro – or opt instead to take up membership of the euroland club. However, the recent sovereign debt crisis in the euro area has, understandably, hardened opinion in the UK against membership of the euro – and some observers have gone so far as to suggest that it has killed off any possibility of UK membership forever! 3.5 Macroeconomic Policy Co-ordination and Political Integration The research so far reviewed here demonstrates the case for an optimum currency area when a group of regions has a high degree of internal market integration for financial assets, productive resources (labour and capital) or outputs. Other properties such as product diversity (see Kenen 1969) and similarities in preferences for particular inflation-unemployment trade-offs have also been proposed as relevant ‘criteria’ for the establishment and sustainability of optimum currency areas. It is important to appreciate that 7 the smooth functioning of a currency area system is dependent on absolute confidence in the permanent fixity of exchange rates and the unlimited convertibility of member currencies inside the area (similarly in the case of a single currency area such as the eurozone). If this is not the case, there is a danger of instability to the system arising from the actions of foreign currency speculators (recall, for example, the exit of sterling from the European exchange rate mechanism in 1992 as Bank of England intervention on the foreign exchange markets, as well as a sharp hike in UK short-term interest rates, failed to turn the tide of capital outflows and halt a dramatic slide in the value of the currency). These conditions for a sustainable OCA require close co-ordination between the national monetary authorities and perhaps even the creation of a supranational central bank (along the lines of the European Central Bank in the case of the euro). However, surrendering national sovereignty over the conduct of monetary policy to a supranational authority involves not only an economic, but also a political process as well as raising questions involving national sovereignty (such questions are, understandably, at the forefront of any debate about the possibility of the UK’s future adoption of the euro). In addition to a high degree of monetary policy co-ordination (and hence the loss of monetary policy independence by member countries), some harmonisation of fiscal policies across the OCA is also necessary. In the face of shocks (such as a sharp slowdown in economic activity leading to rising unemployment) affecting particular regions within the common currency area differently, fiscal transfers away from the relatively prosperous regions towards the adversely affected regions are desirable so as to counteract the impact of the shocks and reduce the burden of real adjustment. It is argued, therefore, that the tax systems inside the currency area must be coordinated in order to avoid the disruptive effects that tax arbitrage behaviour might engender (for example, different corporate tax rates across the area could encourage firms to relocate to lower tax regions). It is not surprising, therefore, that the issue of fiscal harmonisation has been a hotly debated topic within the eurozone – especially in recent times as some countries have deliberately flouted or have been forced to ignore the fiscal rules specified within the Maastricht Treaty. The experience of the European Monetary System (EMS) after its inception in 1979 and the associated Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) has indicated that, without commitment to reaching some form of political integration, managing a currency area as loose as the EMS/ERM is not a simple task (note that the ERM is still in operation following the birth of the euro; other countries which wish to join the euro must be inside the ERM and report a stable exchange rate against the euro for at least two years prior to joining the euroland group). The EMS/ERM may be labelled as a “loose” currency area or a ‘pseudo-exchange-rate union’ (Corden 1972) because occasional currency realignments are allowed (and indeed many have been carried out in the past). Such political commitment can serve as a driving force behind monetary integration and stronger fiscal policy co-ordination. 8 4. Costs and Benefits of Currency Area Participation In order to provide a detailed assessment of the welfare implications arising from participation in an optimum currency area, one would ideally like to examine how the entire world economy should be divided into independent currency areas to maximise global welfare. This approach, of course, is impractical – we do not have the luxury to conduct such an experiment at will. However, a number of research studies have been conducted within a more practical and narrower geographical framework to assess the costs and benefits of OCA participation. Cost-benefit studies by economists such as Ishiyama (1975) and Tower and Willet (1976) have focused on the specific question of whether selected countries should unite with one another to form an optimum currency area. Each country may be assumed to evaluate the costs and benefits of currency area participation from a purely nationalistic point of view. However, the drawback of such a restricted approach is that a ‘nationally’ optimum currency area thus determined may not coincide with a ‘globally’ optimum currency area – the pursuit of self-interest by the individual nations or of the area as a whole may not be in the best interests of the global economy (such self-interest could manifest itself in terms of growing protectionism with respect to international trade). 4.1 Costs of OCA Participation A flexible exchange rate regime, at least in principle, allows each country to retain a degree of domestic monetary policy independence. However, a fixed exchange rate requires unified or closely co-ordinated monetary policy, constraining the participating countries’ freedom to pursue independent monetary policies (membership of a single currency area means a complete loss of monetary sovereignty). This loss of monetary policy independence is considered to be the most important cost of participating in an OCA since it may force the member countries to depart from internal balance for the sake of the maintenance of fixed exchange rates. The cost is deemed large if the country has a low tolerance for unemployment and is subject to strong price and wage pressures from monopolistic industries, labour units and long-term contracts. On the other hand, the cost may be small if it faces a relatively vertical Phillips curve (as in the case of a small, highly open economy), because in such a case the country would not have much freedom to choose the best inflation-unemployment trade-off in the first place (for details concerning the meaning and implications of a vertical Phillips curve see Nellis and Parker, 2004, pp. 274-279). 4.2 Benefits of OCA Participation The primary benefit to a country from participation in an optimum currency area is that the usefulness of money is enhanced (Mundell 1961; McKinnon 1963; Kindleberger 1972; Tower and Willet 1976). Money as a medium of exchange and unit of account simplifies economic calculation and accounting, economises on acquiring and using information for transactions, and 9 promotes the integration of markets, both goods and financial. The use of a single common currency (or currencies rigidly pegged to one another with full convertibility) within an OCA would eliminate the risk of future exchange rate fluctuations, maximise the gains from trade and specialisation and, thus, enhance allocative efficiency (through an optimum allocation of scarce resources between end uses). The usefulness of money generally rises with the size of the domain over which it is used as a medium of exchange – i.e., the larger the currency area, the greater the benefits derived from the use of a single currency. There is also a number of spillover effects (i.e. externalities) which stem from the benefits described above. First, participation in an OCA means that each member country pegs its currency to the class of representative goods traded in the wider area. Hence, a financially unstable country can enjoy a high liquidity value of money by joining a more financially prudent currency area. Secondly, a financially well-integrated OCA supports risk-sharing between the member countries. An inter-regional payments imbalance is immediately accommodated by a flow of financial transactions, which enable a deficit country to draw on the resources of the surplus countries until the adjustment cost is efficiently spread out over time – depending, of course, on the willingness of surplus countries to provide support to the deficit countries. 4.3 Balance of Costs and Benefits It is difficult to assess the balance of OCA participation with respect to the costs and benefits outlined above. Arguments on both sides can be deemed to be more or less important depending on the circumstances prevailing at various points in time. The formation of an OCA must, therefore, be seen as a dynamic process. In terms of the progress towards closer integration involving more complete monetary integration, the confidence of the public and the markets will grow over time. At the same time, some new benefits can be expected to emerge, the significance of existing benefits may increase, and the costs may diminish. Thus, intertemporal balancing of the benefits against the costs is necessary. It can be postulated, therefore, that an individual country will decide to participate in a currency area if the expected (discounted value of future) benefits exceeds the expected (discounted value of future) costs. In assessing the benefits and costs in order to reach a conclusion, two caveats are important to note. First, the country is assumed to compare two extreme exchange rate regimes – i.e., an irrevocably fixed exchange rate system and a free-floating flexible exchange rate system. However, from the viewpoint of maximising the social welfare of the country (in terms of benefits minus costs), there will almost always be an optimal exchange market intervention strategy that allows some exchange rate flexibility and some changes in external reserves. Hence, the polar cases of fixed and flexible exchange rates are unlikely to be optimal – see for example the research reported by Boyer (1978), Roper and Turnovsky (1980) and Aizenman and Frenkel (1985). 10 Second, a small open economy has the freedom to choose the best exchange rate arrangement on the assumption that its choice of policy will not affect the rest of the world (in terms of the volume of capital flows, currency speculation and interest-rate stance). This decision, however, may be affected to some degree by the nature of the policies being pursued by other countries. If the economy in question is not small, the ‘optimum’ currency area thus determined may not be ‘globally’ optimum. As emphasised by Hamada (1985), when the important benefits of currency area formation exhibit public-good characteristics and externalities and the costs are borne by individual countries, the rational theory of collective action (e.g., Buchanan 1969) suggests that individual countries’ participation decisions tend to produce a currency area that is smaller than is optimum from the viewpoint of society’s welfare. Note, however, that if the public-bad character of the costs dominates the public-good character of the benefits, the resulting currency area based on individual calculations may well be larger than that which is globally optimum. The proposed approach of participation (weighing up benefits and costs) obviously neglects a wider variety of strategic interactions among countries; there is no leader-follower relationship and no bargaining or co-operation. Such a game-theoretic approach to optimal exchange rate arrangement has attracted other economists’ attention – see Cooper (1987), Hamada (1985), Canzoneria and Gray (1985) and various research papers in Buiter and Marston (1985). 5. Conclusions This review of the theory of OCAs and the research surrounding the fundamental characteristics as well as the benefits and costs associated with membership, has pulled together a number of issues which merit further attention. First, the choice between flexible and fixed exchange rate regimes should be understood as a second-best solution to the challenges facing economies which exhibit a degree of “friction” (see Komiya 1971). If the markets for outputs, factors of production and financial assets were completely integrated on a world-wide scale, relative prices and real wages were perfectly flexible, and economic nationalism (which attempts to insulate a national economy from the rest of the world by way of artificial impediments to trade, capital movements and foreign exchange transactions) were absent, then the optimum currency area would be the whole world! In such an idealistic situation, the real adjustment to external imbalances would be extremely smooth and relatively painless, factor resources would always be fully employed, and the usefulness of money as a medium of exchange would be maximised (indeed, if the whole world used a single, common currency there would be no issues to be addressed – on a worldwide basis there would be no external imbalances in trade). However, to the extent that the adjustment mechanism is impaired by market fragmentation and price-wage rigidities, a country may adopt flexible exchange rates as a second-best policy to attain internal and external balance. A review of the optimum currency area literature has shown that measures of market integration (concerning financial 11 assets, factor resources and goods) may be more effective, albeit partial, substitutes to price-wage flexibility than is exchange rate flexibility. Second, the cost-benefit approach to optimum currency areas based on purely national interest must be the starting point in the analysis of designing an optimum international monetary system. Given the degree of spill-over effects and economic interdependence among closely integrated countries, the strategic behaviour on the part of national policymakers must be incorporated explicitly in order to deepen our understanding of the nature of ‘globally’ optimum currency areas and optimal international monetary arrangements. Finally, it is interesting to note that the two economists who first advanced the theory of optimum currency areas, Mundell and McKinnon, also came to support fixed exchange rates. Mundell has advocated a world-wide gold standard system and McKinnon (1984) a fixing of the exchange rates among the three major industrialised countries (USA, Germany and Japan). Thus they regard the world as a whole (or at the least the major western) industrialised nations as capable of establishing an optimum currency area on a global scale. We are left wondering to what extent the possibility of such a currency arrangement is ever likely to exist – especially in the light of the rather contrasting performances of the USA, German and Japanese economies over the past two decades. Developments in the eurozone will, undoubtedly, have major and long-lasting implications concerning the pace of closer integration within the European Union. More and more attention is being focussed on the need for fiscal harmonisation between the euro member states in order to avoid renewed sovereign debt crises in the future. This issue is central to the very future and survival of the euro itself – but the extent to which all member governments are prepared to relinquish fiscal sovereignty has yet to be tested. It is hoped that this review of OCA research will provide a useful platform and background for discussions concerning the future of a single common currency in Europe. References Aizenman, J and Frenkel, J 1985, Optimal wage indexation, foreign exchange intervention and monetary policy, American Economic Review 75(3), June: 402-23. Boyer, R S 1978, Optimal foreign exchange market intervention, Journal of Political Economy 86, December: 1045-55. Buchanan, J M 1969, Cost and Choice, Chicago, Markham. Buiter, W H and Marston, R C (eds) 1985, International Economic Policy Coordination, Cambridge; Cambridge University Press 12 Canzoneri, M B and Gray, J 1985, Monetary policy games and the consequences of non-co-operative behavior, International Economic Review 36(3), October: 547-64 Cooper, R N 1987, The International Monetary System, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press Corden, W M, 1972, Monetary Integration, Essays in International Finance No 93, April, Princeton: International Finance Section, Princeton University. Friedman, M, 1953, The case for flexible exchange rates, In M Friedman, Essays in Positive Economics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press Grubel, H G, 1970, The theory of optimum currency areas, Canadian Journal of Economics 3, May: 318-24 Hamada, K, 1985, The Political Economy of International Monetary Interdependence, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press Ingram, J C, 1962, Regional Payments Mechanisms: The Case of Puerto Rico, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press Ishiyama, Y, 1975, The theory of optimum currency areas: a survey, IMF Staff Papers 22 July: 344-83 Kenen, P B, 1969, The theory of optimum currency areas: an eclectic view. In Monetary Problems of the International Economy, ed R A Mundell and A K Swoboda, Chicago: University of Chicago Press Kindleberger, C P, 1972, The benefits of international money. International Economics 2, September: 425-42 Journal of Komiya, R, 1971, Saitekitsukachiiki no riron (Theory of optimum currency areas). In Gendaikeizaigaku no Tenka (The development of contemporary economics), e. M Kaji and Y Murakami, Tokyo: Keisoshobo McKinnon, R I, 1963, Optimum currency areas. American Economic Review 53, September: 717-25 McKinnon R I 1984, An International Standard for Monetary Stabilization. Policy Analyses in International Economics 8, March, Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics Mundell, R A, 1961, A theory of optimum currency areas. Economic Review 51, September: 6457-65. American Nellis, J G, and Parker, D, 2004 Principles of Macroeconomics , Prentice Hall. 13 Phillips, A W 1958, The relation between unemployment and the rate of change in money wage rates in the United Kingdom 1861-1957, Economics 25, November: 283-99. Roper, D E, and Turnovsky, S J, 1980. Optimal exchange market intervention in a simple stochastic macro model. Canadian Journal of Economics 13, May: 269-309 Tower, E, and Willet, T D, 1976, The Theory of Optimum Currency Areas and Exchange-Rate Flexibility. Special studies in International Economics No 11, May, Princeton: Princeton International Finance Section Yeager, L, 1976. International Monetary Relations: Theory, History, Policy. 2nd edn, New York: Harper & Row. 14