Minnesota Integrated Services Project: Voices of Program Participants

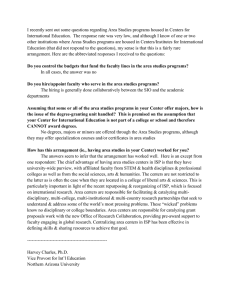

advertisement