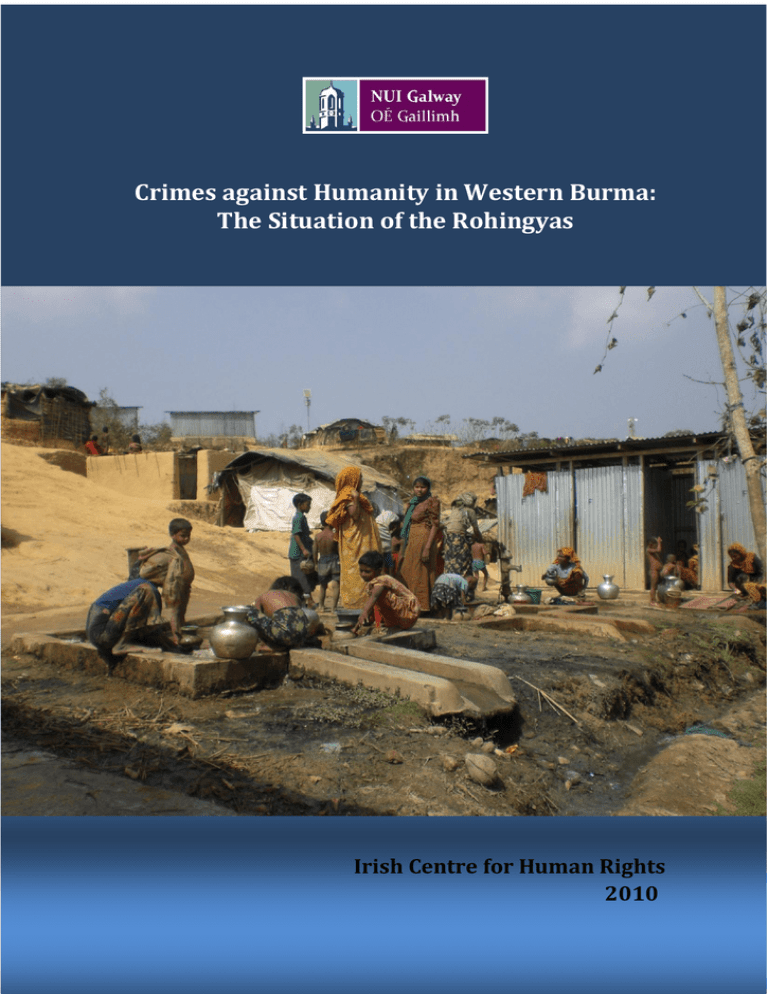

Crimes against Humanity in Western Burma: The Situation of the Rohingyas 2010

advertisement