E O D R

advertisement

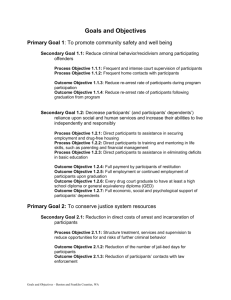

EVALUATION OF THE OHIO DEPARTMENT OF REHABILITATION AND CORRECTION AND CORPORATION FOR SUPPORTIVE HOUSING’S PILOT PROGRAM: INTERIM RE-ARREST ANALYSIS Research Report September 2010 Joshua A. Markman Jocelyn Fontaine John K. Roman Carey Anne Nadeau __________________________ Reentry Research at the Urban Institute In 2000, the Justice Policy Center at the Urban Institute launched an ongoing inquiry into prisoner reentry research to better understand the pathways of successful reintegration, the social and fiscal costs of current policies, and the impacts of incarceration and reentry on individuals, families, and communities. The Institute’s research includes a range of studies, from rigorous program evaluations to strategic planning partnerships with state and local jurisdictions. For more information, see http://www.urban.org/justice. Corporation for Supportive Housing and its Returning Home Initiative The Corporation for Supportive Housing is a national nonprofit organization and community development financial institution that helps communities create permanent housing with services to prevent and end homelessness. In Spring 2006, CSH launched its Returning Home Initiative with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The goal of the Initiative is twofold: to establish permanent supportive housing as an essential component of reintegrating formerly incarcerated persons with histories of housing instability into their communities and to initiate and promote local and national policy changes to better integrate the correctional, housing, mental health, and human services systems. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. Introduction In March 2007, the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (ODRC) and the Corporation for Supportive Housing Ohio Office (CSH) developed a permanent supportive housing pilot program. The pilot was designed to house approximately 100 individuals returning from select prisons throughout Ohio to the Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, and Toledo communities. The 13 institutions participating in the pilot included the Allen, Chillicothe, Grafton, Hocking, London, Lorain, Madison, Marion, Pickaway, and Trumbull Correctional Institutions; the Ohio Reformatory for Women; and the Franklin and Northeastern Prerelease Centers. The pilot, funded primarily by the ODRC, but also a part of CSH’s Returning Home Initiative, has three main goals: to reduce recidivism; to reduce homelessness; and to decrease the costs associated with multiple service use across the criminal justice, housing/homelessness, and mental health service systems. The Urban Institute (UI) is evaluating the pilot to assess the impact on recidivism and residential stability and to test whether the benefits associated with the pilot outweigh its costs. The final report will be complete in summer 2012. In this paper, we report the results of an interim analysis of re-arrest for both the treatment and comparison groups, including descriptive statistics on the study sample. We begin by outlining the pilot model, including eligibility requirements and costs. ODRC/CSH Supportive Housing Pilot Program Key aspects of the pilot included: (1) coordination across the correctional and health services systems, including the ODRC, CSH, the Ohio Department of Mental Health (ODMH), the Ohio Department of Alcohol and Drug Addiction Services (ODADAS), and nine supportive housing providers in the community1; (2) release planning through a reentry coordinator, case manager, or other correctional staff at each participating prison; and (3) the provision of housing and supportive services in five cities. Individuals were eligible for enrollment into the pilot if they were homeless at the time of arrest or at risk of homelessness upon release and had a disability (defined broadly to include developmental disorders, severe addiction, and behavioral problems). Enrollment into the pilot began in March 2007 and is ongoing.2 As of June 30, 2010, the ODRC investment into the pilot totaled more than $3.8 million, which included more than 85 supportive housing beds across the five cities, housing more than 150 individuals released from the 13 prisons. A previous report from UI, published in March 2009, provides a more indepth discussion of the pilot and describes its first cohort of participants.3 Urban Institute Evaluation in offending to estimate whether the pilot improved social welfare. To draw the study sample, UI identified a prospective sample of prisoners released from the target prisons. Individuals receiving permanent supportive housing upon release (treatment group) were compared with a contemporaneous cohort of released prisoners (comparison group) who were eligible for the pilot but did not receive housing due to limited resources. The evaluation team requested signed, affirmative research consents from every individual referred to the pilot and matched information with data from CSH and the providers to determine whether an individual was housed upon release. Data were collected from multiple sources. Programmatic data were collected from the ODRC, CSH, ODMH, ODADAS, and supportive housing providers. Cost data were collected from the ODRC, CSH, ODMH, ODADAS, and supportive housing providers. UI researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with the ODRC, CSH, and supportive housing staff. Finally, electronic and hardcopy official records were collected from the aforementioned government agencies. Findings from the process, impact, and cost evaluations are forthcoming. This interim report offers an initial look at the recidivism outcomes of the individuals in our study. For this report, recidivism is defined as a new arrest. This measure of recidivism (rather than re-incarceration) was preferred since most of the individuals in our sample have not been in the community long enough to experience both a new arrest and a new conviction. It should be noted, however, that while re-arrest is a common indicator of program impact, the pilot is focused mainly on reducing reincarceration and the costs associated with returns to prison. We also note that the use of re-arrest to measure recidivism is less precise with this target population since people with a mental illness may come to greater attention of police and result in increased arrests for crimes such as loitering and other public disturbances.4 Thus, re-incarceration will be the main measure of recidivism studied in the final report. The arrest data were developed by the ODRC from law enforcement data sources in the Ohio Law Enforcement Gateway (OHLEG) search engine as well as county clerk of court websites. Our analyses estimate whether there were differences in the incidence and prevalence of re-arrest and the time to the first re-arrest between the treatment and comparison group. When complete in 2012, the three components of the evaluation will have different, but complementary, objectives. The process evaluation will describe the logic and performance of the pilot and determine whether it achieved short-term objectives, including increased access to permanent supportive housing; increased access to other supportive services, such as mental health and addiction services for participants; and successful provider in-reach to the ODRC prisons. The impact evaluation will test whether the pilot reduced recidivism and increased residential stability. The evaluation will compare the treatment and the comparison groups: rates of re-arrest, number of re-arrests, rates of re-incarceration, changes in types of new offenses, and number of shelter stays. Finally, using data from the impact evaluation analyses, the cost-benefit analyses will compare the costs of service use for all individuals—both treatment and comparison—and the benefits from reductions Sample Enrollment into the study, which began in October 2007 and ended November 2009, was not a condition of enrollment in the pilot program. Therefore, there were fewer individuals in the study’s treatment group than were actually housed by the pilot. When study enrollment ended in November 2009, 240 individuals had consented to participate. Arrest data from the ODRC was requested in July 2010 for all 240 consented participants. Data were received for 233 participants, split nearly evenly between the treatment (119) and comparison (114) group.5 2 treatment group. Precisely half of the full sample was white although there were slightly more non-whites in the treatment group (61 percent). The median age of study participants was 43 years, and almost half of the sample was between 41 and 50 years old. Study Limitations The main challenge in this research is that the data used in this analysis were very limited. The only available data for this interim report are three items describing the study’s demographics (gender, race/ethnicity, and age) and four measures of prison experiences (length of stay, release type, security level, and risk level). As shown in table 1, the two samples were quite different on these limited indicators, notably race/ethnicity and length of stay. Thus, we have limited information about whether the treatment and comparison groups are, in fact, similar. If these dissimilarities relate to recidivism risk, then we will not be able to determine from these limited data whether differences in re-arrest were due to underlying differences in risk or due to differential receipt of services. To address this issue, we ran several different models to adjust for differences in risk. However, with these few variables, we cannot rule out the possibility that differences in the samples—rather than real differences in program effects—explain the results. We tested for differences in the means of key demographic characteristics: gender, race/ ethnicity, age at enrollment into the study, and the number of street days between release date and the date of data collection for the outcome measures. The treatment group was significantly more likely to be non-white and have more street days than those in the comparison group (p < 0.01). No statistically significant differences between the two groups were observed on age at enrollment or gender (table 1). Length of Stay and Release Across the 233 individuals in the sample, the average length of stay for their most recent incarceration was almost 48 months, with a maximum stay of 343 months (about 28 years). The median length of stay was much less—16 months—due to people who had with long prison stays. Although the average length of stay was longer for the comparison group (56 months) than the treatment group (40 months), the difference in means was not statistically significant. Data Analysis—Univariate and Bivariate Analyses Methods To assess whether the treatment and comparison group were comparable using the data available, we conducted univariate and bivariate analyses on each of the variables in our model. The univariate model estimated the mean and standard deviation for each of the variables, including the outcome measures. The bivariate analyses—independent sample ttests—tested whether the difference between the treatment and comparison group means was different from zero. For instance, if the mean for the treatment group is greater than the comparison group mean, this tests whether that difference could have occurred by chance. There were differences in the type of release for the 233 study participants. Most were released by expiration of stated terms (EST— 48 percent), were subject to post-release control (PRC—31 percent) or were paroled (PAR—19 percent). Those with an EST release—equivalent to sentence expiration— were released without supervision. Those with a PRC release completed their sentence but a judge required post-release supervision. Individuals who were released PAR (paroled), completed their minimum prison sentence but remained under the supervision of the ODRC for a designated period. We found no differences between the treatment and comparison groups on post-release supervision levels (table 1). Demographics The 233 participants were comprised of 180 men (77 percent) and 53 women (23 percent). About half of both the women (49 percent) and the men (53 percent) were in the 3 greater security risk than those in the comparison group. Security and Risk We included two measures of security level in our data analysis—one measure for the individual’s security level while incarcerated prior to their most recent release and another measure level for their security level one year prior to their most recent release. Security level classifications ranged from one to five. Level one is the lowest security level in the ODRC and those inmates with a 1A classification are permitted to work in camps, on work crews, and on unsupervised work detail outside prison. Other classifications include 1B, 2, 3, 4A, and 4B, with the riskiest inmates being classified as level 5 (super-max). In addition to security classification, which is based on current conviction and assessments of conduct while incarcerated, the ODRC also classifies inmates’ risk of re-incarceration. The scale ranges from negative one (basic risk) to eight (intensive risk). Efforts are made to target programming toward the riskiest inmates. Most of the sample was classified as “basic risk” and about a quarter had the lowest risk level. Less than 5 percent of the participants in the study were considered by the ODRC as “intensive risk”—or having a risk score of seven or eight. While the treatment groups’ security levels were higher on average than the comparison groups’, we found no statistically significant differences (table 1). Every individual in the sample was in security levels 1A to 3. Nearly everyone in our sample was either classified as 1B (42 percent) or 2 (47 percent). We found that the average current level for the treatment group was significantly higher than the average current security level for the comparison group individuals. This suggests that the treatment group was considered by the ODRC to be a In summary, there were differences observed between the treatment and the comparison group on key indicators such as race/ethnicity, days on the street, and current and previous security level. If those differences are not controlled for in the analysis, they will tend to Table 1. Sample Demographics Age at Enrollment (years) White Male Length of Stay (months) Street Days Release Type (dummy coding) - Expiration of Stated Term - Post-Release Control - Parole Security Level Risk Level Treatment Cases (n = 119) Mean S.D. 42.29 8.55 0.40*** 0.49 0.76 0.43 40.03 66.28 716.90*** 307.8 All Cases (n = 233) Mean S.D. 42.39 9.32 0.50 0.50 0.77 0.42 47.75 78.22 578.63 310.36 Comparison Cases (n = 114) Mean S.D. 42.51 10.09 0.61*** 0.49 0.78 0.42 55.74 88.49 434.3*** 240.2 0.48 0.50 0.50 0.50 0.46 0.50 0.31 0.19 2.54 3.36 0.46 0.40 0.69 1.87 0.32 0.16 2.64** 3.51 0.47 0.37 0.69 1.85 0.30 0.23 2.43** 3.21 0.46 0.42 0.69 1.88 Source: Urban Institute analysis of data from the ODRC. Note: The independent samples t-test tests whether the difference in the means of the treatment group and the comparison group is significantly different from zero. . Significance testing: * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. 4 Among those in the comparison group who were re-arrested, 47 percent were for felony offenses and 53 percent were for misdemeanor offenses. Of the individuals who were re-arrested, the median number was 1 re-arrest, and the maximum number was 15. Half of those who were re-arrested were rearrested only once, 24 percent were rearrested twice, 12 percent were re-arrested three times, and the remaining 13 percent were re-arrested four or more times (figure 1). Of those 84 individuals who were rearrested, the number of days to their first rearrest ranged from 2 days to 952 days (approximately two and a half years), with the median number of days to re-arrest of 151 days. The sample enrollment spanned more than two years; therefore, some of the sample was in the community longer than others with more time to be re-arrested. Of those who were re-arrested, the majority (85 percent) were re-arrested in less than one year (figure 2). bias the results to the extent they also predict recidivism. In addition to risk measures, the treatment group spent significantly more time on the street, which exposed the group to more opportunities to be arrested. Therefore, multivariate analyses discussed below included control variables to assess whether these differences are related to re-arrest outcomes. However, if important predictors of risk were omitted from this analysis, as they surely were, then even those statistical controls may not be sufficient to balance the samples and allow an apples-to-apples comparison. Re-arrest Outcomes Of the 233 individuals in the sample, 84 were re-arrested during the study period (36 percent of the study sample). Of the 84 who were re-arrested, 57 percent were in the treatment group and 43 percent in the comparison group. Among those in the treatment group who were re-arrested, 50 percent were for felony offenses and 50 percent were for misdemeanor offenses. Figure 1. Description of Sample Outcomes – Number of Re-arrests 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 0 1 2 As reported by the ODRC N: 233 5 3 4 and up for a large number of zeros (zero-inflated negative binomial regression) and tested the goodness of fit for models using the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). Based on the AIC, the negative binomial regression was selected. Finally, when modeling the “time to re-arrest,” we used a Cox proportional-hazards model. Typically referred to as a survival analysis, this analysis models the time (in days) to the first new re-arrest. Table 2 shows the univariate and bivariate statistics for the outcomes: any re-arrest, number of re-arrests, and time to re-arrest. The mean number of treatment group rearrests was significantly more than the number of comparison group re-arrests. No statistically significant differences between the treatment and comparison group were observed when comparing the prevalence of re-arrest or time to re-arrest. For each of the three outcome measures, we specified five models of the effect of pilot participation on re-arrest. This was done iteratively to adjust for variables that may independently explain re-arrest. First, we regressed each re-arrest outcome on a binary indicator of receiving the treatment or not (e.g., whether the individual was in the treatment or comparison group). To test whether those differences were due to differences in group attributes and experiences, the second model includes demographic measures, street days, length of stay, and release variables. The third model adds the security and risk variables. The fourth Data Analysis—Multivariate Statistics Methods In the multivariate analyses, a different regression model was specified for each of the three outcomes. When the measure was “any re-arrest,” a logistic regression tested whether there were differences in the mean likelihood of re-arrest between the treatment and comparison group. When the measure was the “number of re-arrests,” we used a negative binomial regression to test whether the number of re-arrests varied by group. Note that we also specified count models to adjust Figure 2. Description of Sample Outcomes – Days to First Re-arrest 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% 160 61120 121180 181240 241300 301365 As reported by the ODRC N: 84 Note: Of the 233 individuals, 149 were not re-arrested and 1 re-arrest was missing a date. 6 365 and up after either adding covariates to the model or replacing the covariates with the propensity weight. This process tests whether our control variables predict a different group assignment than we actually observe in the data. The difference between predicted and actual assignment is not statistically significant suggesting that the treatment and comparison groups are comparable based on the data observed. Second, we used the AIC to choose among competing models, as previously mentioned, when the number of re-arrests was the outcome measure. The results from the AIC test show that the negative binomial regression is the best fit for the distribution in the data. However, these corrections will not control for unobserved bias if important predictors are missing from our models. model adds an additional variable, the square of the risk score6, to test whether those at most serious risk of re-arrest explain differences in outcomes. Unlike the previous four models that adjust for the relative risk of re-arrest by controlling for underlying differences in the groups, the fifth model simply adds a weight to the bivariate models to adjust for group differences. We calculate this weight as a propensity score that is the conditional probability of being assigned to the treatment group based on the demographic, detention, release, security, and risk variables as well as days on the street. The intuition behind the propensity score weight is that there may be variables that predict whether an individual is accepted into the treatment group that are also related to the likelihood of re-arrest. So, if the treatment group is at higher risk of re-arrest, this approach will re-weight the samples to adjust for those differences. These scores are calculated as the inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW), which is the inverse of the probability score. The IPTWs are weighted based on the entire sample. Results For each outcome, we tested five model specifications on each of the three measures: any re-arrest, number of re-arrests, and time to first re-arrest (tables A.1-A.3 in Appendix A). Of the five models specified, we report on the fifth model, which utilizes propensity weights (table 3). We prefer the propensity weighted models as they efficiently use all of the information contained in the data to reduce selection bias. Diagnostics To test whether these models effectively balance the samples and allow for a fair comparison, we compared observed group assignment to the predicted group assignment Any re-arrest was modeled using logistic Table 2. Univariate and Bivariate Sample Outcomes by Recidivism Measure Any Re-arrest Number of Re-arrests Time to First Re-Arrest (days) All Cases (n = 233) Mean S.D. 0.36 0.48 Independent Samples T-Tests Comparison Cases Treatment Cases (n = 114) (n = 119) Mean S.D. Mean S.D. 0.40 0.31 0.32 0.47 0.84 1.80 1.10** 2.23 0.56** 1.15 214.49 190.23 223.60 209.00 202.40 164.00 Source: Urban Institute analysis of data from the ODRC. Note: The independent samples t-test tests whether the difference in the means of the treatment group and the comparison group is significantly different from zero. The sample size for Time to First Re-Arrest is as follows: N = 84; Treatment = 48; Comparison = 36. Significance testing: * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. 7 the treatment group compared with the comparison group in the model that uses the propensity score weights. Finally, we find that the general direction of the results suggest more time before first re-arrest in the treatment group than we find in the comparison group. While this is the general direction, the results are not statistically significant. Thus, our findings are somewhat mixed, suggesting the treatment group was rearrested more—and more often—but took longer to do so. regression. The coefficient estimate 0.510 suggests that the treatment group is rearrested more than we observe in the comparison group. Our model of the number of re-arrests estimates a coefficient 0.660 which suggested that the number of re-arrests is significantly higher in the treatment group than in the comparison group. Finally, we modeled a Cox Proportional Hazard model, which estimated a negative coefficient (-0.098). This suggested that the time to re-arrest is longer for the treatment group as compared to the comparison group. Despite these analyses, however, the findings may be an artifact of limited data. We could not observe many important facts about the individuals in the sample, so it is difficult to assess whether the differences were due to program impacts or underlying differences in the risk of re-arrest. For example, we note that the individuals targeted by the pilot had at least one disability and were homeless at the time of arrest or at risk of homelessness upon release. While data were not available to control for these variables, the presence of a disability or risk of homelessness may be associated with a greater risk of re-arrest. If this is true, then our samples were not comparable along unobserved measures that may explain the treatment groups’ outcomes. Additional variables not included in the analysis might reveal disparities in the group assignment such as mental health, disability, and homelessness. Exploration of the relationships among these variables and others, and group assignment, may reveal a selection bias that, once accounted for, changes the estimated program impact. We anticipate that we will have these data available for the final report. It is important to note, however, that the results of the propensity models differ in magnitude from the models with covariates (but are quite similar to the bivariate analyses). That is, the direction and size of the effect when the treatment and comparison groups are compared with no controls is very similar to the direction and size of the effect using the models with propensity scores. However, the propensity score and bivariate models show bigger (negative) effects of treatment than is observed in the models with covariates. While all but one of the models show consistent results (e.g., that the introduction of different groups of controls does not change the general finding), the covariate models consistently show non-significant effects. The choice to highlight the propensity weights is based on statistical tests (not shown but available from the authors) that suggest that the control variables and the group assignment variable significantly covary. Thus, the coefficient on any single variable, including the group assignment variable, is unreliable. This problem is not present in the propensity weighted models. Conclusions Another potential explanation for the higher number of re-arrests observed in the treatment group are disparities in supervision intensity. Individuals in supportive housing are likely to be monitored more closely by community corrections officials and housing and service providers than are individuals who are not in supportive housing. This seems sensible since individuals in the pilot were housed in central city locations that may lead to heightened contact with case managers, housing specialists, and other staff who might The results of these analyses suggested that those who received permanent supportive housing were more likely to be re-arrested and to have more re-arrests than those who did not receive housing, although this relationship may be spurious, as discussed below. We observe higher odds of re-arrest for those in the treatment group in the model that uses the propensity score weights. Similarly, we observe more re-arrests among 8 readily report criminal activity. If treatment group members were more closely supervised, differences in re-arrest may have been due to closer observation and certainty of detection rather than differences in offending behavior. sample has been recruited fully, the evaluation team is collecting additional data for the evaluation. Additional data will include baseline and follow-up data from the housing/service providers on the experiences of those who are housed, semi-structured interviews with the housing/service providers, and administrative data from the ODMH, the ODADAS, and the local shelters in the five cities where the pilot is based. Using all of these data to inform the process, impact, and cost evaluation, the final analyses will be reported in summer 2012. Time to first re-arrest (and the number and likelihood of re-arrest) may also be an artifact of our limited data. We observe that the treatment group had significantly more street days than did the comparison group—about nine months more street days. Thus, the individuals in the treatment group were exposed to more days where they were at risk of re-arrest than individuals in the comparison group. 1 The nine housing/service providers that have been associated with the pilot include: Amethyst, Inc (Columbus); Community Housing Network (Columbus); EDEN, Inc. (Cleveland); Miami Valley Housing Opportunity (Dayton); Mental Health Services (Cleveland); Neighborhood Properties, Inc. (Toledo); Volunteers of America—Northwest Ohio (Toledo); Volunteers of America—Ohio River Valley (Cincinnati); and YMCA of Central Ohio (Columbus). EDEN and Mental Health Services worked in a partnership, where EDEN managed the housing component of the pilot and Mental Health Services managed the services component. 2 Though enrollment into the pilot is still ongoing, the housing program has continued in the same prisons as a full program of the ODRC. 3 See J. Fontaine, C.A. Nadeau, C. Roman, and J. Roman, “Evaluation of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction and Corporation for Supportive Housing’s Pilot Program, Interim Report: October 2007 – September 2008” (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2009). 4 Council of State Governments, “Criminal Justice Mental Health Consensus Project” (New York: Council of State Governments, 2002); P. Hirschfield, T. Maschi, H. R. White, L. G. Traub, and R. Loeber, “Mental Health and Juvenile Arrests: Criminality, Criminalization, or Compassion?” Criminology 44 (2006): 593–630. 5 Data from the ODRC were not available for seven individuals, including five who are still incarcerated, one whose record was not in the ODRC files, and another one who had no data. 6 Squaring the risk term creates bigger differences between each level of risk, especially for those with very high levels. For example, risk values of 1, 2, 3, and 4 would be 1, 4, 9, and 16 in the squared term. This increases the variance to allow us to test whether those with the most serious risk levels had different outcomes than for those with other risk levels. However, we did not have any detention information for individuals after they enrolled in the study. Individuals who were re-arrested could have been detained before trial or after conviction. This is important to note; since, it means we were unable to adjust our time on the street estimate for these detention stays. Once this additional information is obtained and included in the analysis, the time on the street we observed in the data could be reduced for both the treatment and comparison groups. Changes to this variable would affect all of the recidivism measures reported in this document. The final evaluation will use data from various sources to create a more complete picture of the sample’s histories, characteristics, and outcomes. The evaluation will assess other key variables to gain a better understanding of whether permanent supportive housing reduces recidivism. In addition, re-arrest will not be the only recidivism measure considered; we will also explore differences between the treatment and comparison groups on re-incarceration and offending types. The final report will test the pilot’s goals on reducing re-incarceration, an analysis the time limitations prevented for this interim report. Next Steps While the analyses presented here were based solely on data from the ODRC, the full evaluation relies on multiple methods to assess the process, impacts, and costs and benefits associated with the pilot. Now that the study 9 Appendix A Table A.1. Multivariate Outcomes – Logistic Regression of Any Arrest Treatment (1) 0.382 (0.275) Age at Enrollment (years) - White - Male - Length of Stay (months) - Street Days x 30 - (2) -0.122 (0.146) -0.0277 (0.017) -0.4036 (0.300) 0.917** (0.378) -0.008** (0.003) 0.012 (0.03) (3) 0.2175 (0.3422) -0.0241 (0.0188) -0.2471 (0.3125) 1.0595*** (0.3954) -0.00652* (0.00336) 0.008 (0.016) (4) 0.2601 (0.3481) -0.0256 (0.0195) -0.1808 (0.3179) 1.0154** (0.397) -0.00625* (0.0034) 0.007 (0.017) -0.695 (0.507) -0.771 (0.504) -0.3585 (0.5264) -0.5549 (0.5203) -0.2168 (0.35) 0.2981*** (0.0913) -0.4653 (0.5342) -0.6908 (0.5317) -0.1462 (0.3525) 1.3419*** (0.4043) -0.1379*** (0.0512) 283.6 232 (5) 0.510** (0.242) - Release Type - Expiration of Stated Term - - Post-Release Control - Security Level - - Risk Level - - Risk Quadratic - - - 306.7 233 300.5 232 289.3 232 AIC N 434.7 232 Source: Urban Institute analysis of data from the ODRC. Note. Each column reports selected coefficients from a logistic regression. The coefficient on treatment is the expected change in the recidivism measure any arrest from being in the treatment group as opposed to the comparison group. Positive values would indicate that the treatment group is recidivating more than the comparison group, while negative values indicate that the comparison group is recidivating more than the treatment group. Significance testing: * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01 Table A.2. Multivariate Outcomes – Negative Binomial Regression of Number of Re-Arrests Treatment (1) 0.673*** (0.257) Age at Enrollment (years) - White - Male - Length of Stay (months) - Street Days x 30 - (2) 0.316 (0.290) -0.0342* (0.017) -0.115 (0.264) 0.6765* (0.3304) -0.004 (0.003) 0.027* (0.015) (3) 0.320 (0.292) -0.026 (0.017) 0.068 (0.270) 0.695** (0.3263) -0.004 (0.003) 0.024 (0.015) (4) 0.396 (0.282) -0.029* (0.017) 0.145 (0.262) 0.7758** (0.3153) -0.003 (0.003) 0.018 (0.015) 0.383 (0.469) 0.2276 (0.468) 0.677 (0.464) 0.380 (0.458) -0.322 (0.286) 0.231*** (0.082) 0.496 (0.450) 0.109 (0.448) -0.217 (0.276) 1.636*** (0.358) -0.1839*** (0.045) 535.6 232 (5) 0.660*** (0.235) - Release Type - Expiration of Stated Term - - Post-Release Control - Security Level - - Risk Level - - Risk Quadratic - - - 565.1 233 559.2 232 551.1 232 AIC N 569.4 232 Source: Urban Institute analysis of data from the ODRC. Note. Each column reports selected coefficients from a negative binomial regression. The coefficient on treatment is the expected change in the recidivism measure number of re-arrests from being in the treatment group as opposed to the comparison group. Positive values would indicate that the treatment group is recidivating more than the comparison group, while negative values indicate that the comparison group is recidivating more than the treatment group. Significance testing: * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01 Table A.3. Multivariate Outcomes – Cox Proportional-Hazards Regression of Time to Re-Arrest Treatment (1) -0.121 (0.223) Age at Enrollment (years) - White - Male - Length of Stay (months) - (2) -0.184 (0.267) 0.0235 (0.017) 0.2974 (0.241) 0.101 (0.343) -0.003 (0.003) (3) -0.3306 (0.2828) 0.0306* (0.0177) 0.2653 (0.240) 0.191 (0.350) -0.004 (0.003) (4) -0.3839 (0.2843) 0.0358** (0.0183) 0.2946 (0.2424) 0.156 (0.351) -0.003 (0.003) 0.142 (0.381) 0.232 (0.375) 0.271 (0.385) 0.344 (0.383) -0.636** (0.278) 0.078 (0.084) 0.377 (0.391) 0.530 (0.411) -0.739** (0.291) -0.475 (0.395) 0.067 (0.047) 568.6 82 (5) -0.098 (0.201) - Release Type - Expiration of Stated Term - - Post-Release Control - Security Level - - Risk Level - - Risk Quadratic - - - 584.7 84 572.9 82 568.6 82 AIC N 782.8 84 Source: Urban Institute analysis of data from the ODRC. Note. Each column reports selected coefficients from a Cox proportional-hazards regression. The coefficient on treatment is the expected change in the recidivism measure time to first re-arrest from being in the treatment group as opposed to the comparison group. Positive values would indicate that the treatment group is recidivating more than the comparison group, while negative values indicate that the comparison group is recidivating more than the treatment group. Significance testing: * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01