50 FIElD DAy REVIEw

advertisement

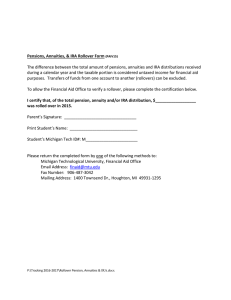

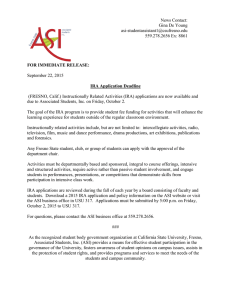

Field Day review 50 ‘Everyone Trying’, the IRA Ceasefire, 1975: A Missed Opportunity for Peace? Niall Ó Dochartaigh Introduction 1 At this point the Official IRA was still a significent political force and a serious claimant to the title of ‘IRA’. For ease of use, however, the Provisional IRA will simply be referred to as the IRA hereafter in this essay. British soldiers arrest an anti-internment demonstrator, Divis Street, Belfast, August 11 1975. Photo: Keystone © Getty Images For most of 1975 the Provisional IRA1 was officially on ceasefire. The ceasefire constituted a major and sustained political initiative by the Provisionals, despite the fact that there was a variety of breaches and that sectarian violence escalated during this period. The fact that it was maintained for such a long period, albeit imperfectly, raises the question of why it did not provide the basis for a lasting peace. It was the first time since its establishment in 1970 that the IRA had maintained a ceasefire for more than a few Field Day Review 7 2011 51 Field Day review weeks. It was not until 1994 that the IRA would again maintain a ceasefire for a comparable duration. The 1994 ceasefire was a direct precursor to republican acceptance of major compromises in the comprehensive peace settlement of 1998. Why was it that the IRA ceasefire of 1975 did not provide the basis for a settlement, given that a long IRA ceasefire was a crucial element in permitting the negotiation of an inclusive peace agreement in the 1990s? Throughout the course of the 1975 ceasefire, British government representatives held regular secret talks with a republican team that was reporting directly to the IRA Army Council. It was the only time in the conflict that such a series of meetings took place. In the wake of these talks the British government turned away from efforts to negotiate and focused its attention on the military defeat of the IRA. Existing accounts characterize these talks as a deliberate British government ploy to weaken the IRA and argue that the talks and the ceasefire were only sustained by the pretence of the British government that it was considering withdrawal. They argue that a simplistic republican analysis of the British state, republican misreading of British intentions, and a dogmatic focus on rigid ideological goals ensured that the talks never had any prospect of delivering a permanent peace agreement. The ideological rigidity of the IRA is identified as a central reason for the failure of these negotiations. This essay offers an alternative analysis of these talks. While acknowledging that republicans overestimated the likelihood of British withdrawal, I argue that republicans had a more nuanced analysis of British intentions than suggested by other accounts and that the IRA was seriously considering a settlement that would involve major compromise and a significant shift in the republican position. The breakdown of the talks cannot be ascribed primarily to republican ideological dogmatism. 52 Interpreting the Ceasefire 2 The fact that the ceasefire presents a puzzle is widely recognized by scholars of the period, even by those whose hostility to the IRA is strongest. From the hostile baseline assumption of republican ideological extremism and determined militarism adopted by many scholars of the period, it is difficult to explain why the IRA should have sustained a ceasefire for so long after it became clear that it could neither yield military benefits nor meet its core ideological demands. Analyzing IRA decision-making in terms of military strategy, M. L. R. Smith comments: The ceasefire ... begs the question, why did the Provisionals, both moderates and hardliners alike, allow themselves to be ensnared in a ‘demoralising’ and ‘damaging’ truce for so long? ... they persisted even after it was clear ... that the British were not interested in talking to IRA and were busily pursuing their own political agenda with the constitutional convention. 2 The dominant explanation in the academic literature for the lengthy IRA ceasefire of 1975 is that the republican leadership was duped by the British government into believing that British withdrawal was on the cards. Jonathan Tonge states it baldly: ‘Duped by the British government that withdrawal might be on the agenda, the IRA leadership called a cease-fire in 1974–5.’3 Paul Bew and Henry Patterson offer a variation on the same theme: ‘The purpose of the truce was to divide and weaken the Provisionals and to get rid of internment, as prelude to reasserting the rule of law ... the true nature of that policy was revealed in 1976.’4 According to this explanation, the British government strung out the talks in order to weaken the IRA militarily and politically, laying the foundation for the subsequent success of security force action against the IRA. The chief source for this explanation 3 4 M. L. R. Smith, Fighting for Ireland? The Military Strategy of the Irish Republican Movement (London, 1997), 133. After the collapse of the Sunningdale agreement and the power-sharing executive in 1974, the British government held elections in May 1975 to a Constitutional Convention that was intended to make proposals for the future government of Northern Ireland. The Provisionals boycotted the election and the convention. The unionist parties at the convention ultimately recommended a return to unionist majority rule, modified only by the inclusion of the SDLP in all-party parliamentary committees. This proposal was rejected by the British government, which then prepared to settle into a period of extended direct rule. J. Tonge, Northern Ireland: Hotspots in Global Politics (Cambridge, 2006), 48. P. Bew and H. Patterson, The British State and the Ulster Crisis: From Wilson to Thatcher (London, 1985), 87. ‘Everyone Trying’ 29 May 1974: Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Merlyn Rees at 10 Downing Street for an emergency meeting. ©Getty Images. 5 6 M. Rees, Northern Ireland: A Personal Perspective (London, 1985). See Smith, Fighting for Ireland; Bew and Patterson, The British State and the Ulster Crisis; P. Dixon, Northern Ireland: The Politics of War and Peace (Basingstoke, 2001); P. Neumann, Britain’s Long War: British Strategy in the Northern Ireland Conflict, 1969–98 (Basingstoke and New York, 2003); and J. Tonge, Northern Ireland: Conflict and Change (Harlow, 2005). is the memoirs of the secretary of state for Northern Ireland at the time, Labour MP Merlyn Rees, where it is expounded at some length. 5 Many academic accounts of the ceasefire accept Rees’s argument to a greater or lesser degree.6 Rees’s account of a strategy of deception also finds some support in contemporary official documents, in particular the minutes of meetings of the Cabinet Committee on Northern Ireland. At these meetings Rees regularly told his colleagues that government strategy during the ceasefire was directed at weakening the IRA. Thus, at a meeting on 18 February 1975 he told colleagues that: ‘The importance of a ceasefire is that it offers us the opportunity to create the conditions in which the Provisionals’ “military” organisation and structure may be weakened. They would not find it easy to 53 Field Day review start a campaign again from scratch.’ But in the same memo Rees noted: As against this, there is the risk that the Provisionals can rest, re-supply and regroup so as to re-emerge more strongly ... They badly needed a ceasefire if only in order to reorganise after a long period of attrition and disruptions at the hands of the Security Forces. But they are not beaten. Their cohesion and discipline are remarkable.7 Throughout the ceasefire, the question of whether it had weakened or strengthened the Provisionals continued to be hotly contested. In May 1975, for example, the head of the British army in the North, General Sir Frank King, and his senior officers complained to Rees that: ‘The PIRA were becoming stronger every day, but the Security Forces were becoming weaker ... It would take a considerable time now to reverse the PIRA’s new-found strength.’8 In one sense the jostling for advantage by both sides in the event of a breakdown is an entirely unremarkable and predictable element of the ceasefire. Rees came under intense criticism for the concessions that had been made to the IRA in order to secure and maintain the ceasefire. It is to be expected that he would emphasize, in his own defence, that his main aim was the weakening of the IRA but, even then, he was simultaneously offering the prospect of a negotiated settlement to his colleagues, aiming, he said, ‘to look for the outside chance of reaching some more substantial settlement with the Provisionals should they be sufficiently tired of violence to want to give up’.9 One significant variation on the theme of deception holds that the British government entered talks with the intention of ‘politicizing’ the IRA and incorporating it in the political life of Northern Ireland, but abandoned this approach when it became clear that it would lead nowhere. According to Desmond Hamill: ‘As officials explored the openings they began to realize 54 that the Provisionals lived in a “dream world” and did not understand the facts of political life.’10 This is more or less a direct restatement of the analysis presented by Rees himself, who asserted that: At the beginning of the ceasefire I had thought there was at least a chance of the Provisional IRA getting itself involved in the politics of the [Constitutional] Convention but the reports to me of the talks with the Provisional Sinn Féin had soon shown that real politics were outside its ken.11 Rees emphasized that the British turned to deception only after it became clear that the IRA could not be incorporated in the political system. Here, he identified republican ideological rigidity as the central obstacle to a negotiated settlement. This account has strong attractions for key figures on all sides of the political debate. For Rees and the Labour administration at the time it served to protect them from denunciation as traitors who, in order to maintain the ceasefire, were undermining a successful military campaign against the IRA. At one stage, Ulster Unionist MP Enoch Powell publicly accused civil servants dealing with Sinn Féin of being engaged in ‘near treasonable activities’, while Rees recorded that he himself was called a ‘traitor’ in the House of Commons.12 Thus, when Rees represents these talks as a successful security initiative, laying the groundwork for the subsequent reduction in violence in the late 1970s, it is partly in response to the hostile criticism that he was engaged in a misguided and even treacherous attempt to achieve a negotiated settlement with evil and incorrigible terrorists. In part, this account has taken such a firm hold because it suited the new leadership which took over control of the republican movement in the years after the ceasefire. This version of events depicted the old leadership as generally incapable and so strengthened the arguments for 7 Memo on IRA ceasefire from Merlyn Rees to IRN (75), Cabinet Committee on Northern Ireland, 18 February 1975, CAB 134/3921, UK National Archives. 8 ‘Force levels and the ceasefire. Note of a meeting held at 2.15pm on Friday, 2 May 1975’, CJ4/839, UK National Archives. 9 Memo on IRA ceasefire from Merlyn Rees to IRN (75), Cabinet Committee on Northern Ireland, 18 February 1975. 10 D. Hamill, Pig in the Middle: The Army in Northern Ireland, 1969–84 (London, 1985), 177. 11 Rees, Northern Ireland, 248. 12 Rees, Northern Ireland, 243, 245. ‘Everyone Trying’ 13 E. Moloney, A Secret History of the IRA (London, 2002), 138, 142–44, 169–70. 14 T. P. Coogan, The Troubles (London, 1996), 259. 15 Moloney, A Secret History of the IRA, 141, 177. 16 J. Bew, M. Frampton, and I. Gurruchaga, Talking to Terrorists (London, 2009), 57–58. 17 The Ruairí Ó Brádaigh Papers at the Archives, James Hardiman Library, National University of Ireland, Galway, POL 28. pushing it aside. For the new leadership of Sinn Féin and the IRA in the late 1970s, this account of a perfidious Albion and a near-fatal republican weakness confirmed the strong suspicions of many IRA volunteers that the old leadership had come close to selling them out during the ceasefire. It validated in retrospect the strong opposition to the talks that had been expressed in Derry, Belfast and South Armagh and strengthened those who had opposed the ceasefire.13 Some elements of this account also suit the republican leadership that called the 1975 ceasefire. For example, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, former president of Provisional Sinn Féin, argues that the British initially favoured withdrawal but moved away from this position under pressure from loyalists and the Irish government.14 This is compatible with the proposition that, while the British employed deception (at least during the later stages of the ceasefire), the leadership in 1975 stood firmly by republican principles in exploring a genuine opportunity for British withdrawal, unlike the leadership of the 1990s, which accepted a partitionist settlement. But, in emphasizing that republicans engaged in talks only because of the prospect of British withdrawal, this account can be used to confirm the argument that the republican position in these talks was ideologically rigid and that there was therefore no reasonable prospect of a negotiated compromise. However, some recent work has begun to explore the weaknesses in these accounts of deception. Ed Moloney, for example, raises doubts about the claim that the ceasefire was a successful move to weaken the IRA, citing a former senior IRA member who told him: ‘I can’t understand these people who say that the truce wrecked us. In my view it strengthened us ... the cease fire was a godsend.’15 At the same time, John Bew, Martyn Frampton and Iñigo Gurruchaga note that the British government considered withdrawal in 1975 rather more seriously than it was subsequently comfortable to admit.16 But even these accounts leave intact the characterization of republican ideology as an immovable obstacle to a negotiated compromise in 1975. There are in fact strong grounds for believing that both parties to the 1975 talks entered negotiations with the genuine aim of exploring the potential for a negotiated compromise that would resolve the conflict and end violence, and that both sides were prepared to consider major compromises to that end. Contrary to the received wisdom, the talks were neither a British ploy to weaken the IRA nor the product of a deluded IRA assessment that it had achieved victory. Existing accounts of the 1975 ceasefire operate either with a very thin concept of negotiation or with none at all. To understand the 1975 ceasefire and its collapse it is necessary to bring negotiation fully back into the story and to analyze the 1975 talks as a negotiating process, tracing a number of key themes through this process and identifying some of the key factors that contributed to the failure of this initiative. Analyzing these talks as negotiations allows us to provide an alternative explanation of the end of a ceasefire that had initially promised so much. Sources A number of important new sources on the 1975 ceasefire have become available over the past decade, beginning with the deposit at National University of Ireland, Galway, in 2005 of Ó Brádaigh’s notes of meetings with British representatives.17 Under the thirty-year rule, the relevant official British records for the period were opened at the UK National Archives from 2005 onwards. These records have been drawn on intensively in a number of recent publications, but there is much more to be gleaned from them, particularly on the tensions between the Labour government and the security forces. Most recently, the quiet deposit of key IRA leader David O’Connell’s (Daithí Ó Conaill) extensive 55 Field Day review private papers at the National Library of Ireland made available an important new source, which, it seems, has not yet been consulted by scholars.18 The papers shed new light on O’Connell’s contacts with unionists and loyalists and his attempts to formulate a flexible negotiating position. One of the most important sources to become newly available is the private papers of Brendan Duddy, who acted as intermediary between the British government and the IRA before and during the 1975 ceasefire. Duddy played a crucial central role in these negotiations, reflected in the fact that his house was the venue for all of the regular meetings between the British government and the IRA during the ceasefire.19 The role that Duddy played was first outlined by Peter Taylor in the late 1990s, but his identity remained secret for another decade.20 It was only in 2008 that his role was publicly acknowledged in a BBC documentary, The Secret Peacemaker. His papers, deposited at NUI, Galway, in 2009, include his personal diaries of the negotiation in 1975 and 1976, along with a range of other primary documents from that period.21 The account outlined here also draws on many hours of interviews with Brendan Duddy, conducted on multiple occasions between 2004 and 2009, and on interviews with key figures involved in these negotiations on both the republican and British sides.22 It draws, too, on biographies, autobiographies and secondary historical sources that shed light on the 1975 ceasefire. British Policy and Republican Strategy Many of the accounts that argue that the British government duped an ideologically rigid republican movement assume that the British government was not seriously considering an initiative that could be labelled ‘withdrawal’. They also assume that the republicans were characterized by political ‘primitivism’, to use Bew and Patterson’s provocative characterization 56 of IRA understandings of British policy.23 That is, they were not viable negotiating partners, but they could be successfully deceived. It is important to begin by questioning the accuracy of both of these assumptions. British Deception? The narrative of British deception assumes that the British state never seriously considered a compromise solution that had a serious chance of acceptance by the IRA. This is plainly incorrect. When Labour took office under Harold Wilson in 1974, it brought to power a prime minister whose stated personal preference in his fifteen-point speech of November 1971 was for an arrangement that would permit British withdrawal through the granting of dominion status to Northern Ireland; he had even spoken of ‘finding a means of ... progressing towards a United Ireland’.24 As leader of the opposition, he had personally met with IRA leaders, including David O’Connell in Dublin in March 1972, and again at his country home in England in July 1972.25 Wilson was strongly attracted to the option of British ‘disengagement’ or ‘withdrawal’ and remained an advocate of this option to one degree or another throughout the year of secret talks with the IRA. His May 1974 speech, delivered without consultation with his advisers, 26 in which he referred to Ulster loyalists as ‘spongers’ after the Ulster Workers’ Council (UWC) strike had brought about the collapse of the powersharing executive at Stormont and the Sunningdale Agreement, provided a public indication of his distance from unionism and his distaste for continued British commitment to Northern Ireland. His close advisers, Bernard Donoughue and Joe Haines, whose presence in government was intended to act as a counterweight to the conservatism of the civil service ‘machine’, both expressed strong support at different stages for withdrawal. In his memoir of 18 Daithí Ó Conaill Papers in the Seán O’Mahony Papers, National Library of Ireland, MS130. O’Connell used the Irish form of his name, Daithí Ó Conaill, in his official capacity, but was generally known to family, friends and colleagues by the English form. 19 See N. Ó Dochartaigh, ‘“The Contact”: Understanding a Communication Channel between the British Government and the IRA’, in N. Cull and J. Popiolkowski, eds., Track Two to Peace: Public Diplomacy, Cultural Interventions and the Peace Process in Northern Ireland (Los Angeles, 2009), 57–72; N. Ó Dochartaigh, ‘Together in the middle: Back-Channel Negotiation in the Irish Peace Process, Journal of Peace Research 48, 6 (2011); and N. Ó Dochartaigh and I. Svensson, ‘The Exit Option: Mediation and the Termination of Negotiations in the Northern Ireland Conflict’, International Journal of Conflict Management (forthcoming). 20 P. Taylor, Provos: The IRA and Sinn Fein (London, 1998); see also, P. Taylor, Brits: The War against the IRA (London, 2001). 21 The Brendan Duddy Papers at the Archives, James Hardiman Library, National University of Ireland, Galway, POL 35. 22 Details of interviews: Brendan Duddy, Derry, interview dates include 11–13 May 2009, 27–29 July 2009, 13–16 October 2009 and 26–27 November 2009; Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, Roscommon, 2 December 2009; unattributable interview with former British official, 7 October 2008. 23 Bew and Patterson, The British State and the Ulster Crisis, 88. 24 Coogan, The Troubles, 156. ‘Everyone Trying’ Future Prime Minister James Callaghan whispers in the ear of the serving prime minister Harold Wilson during the Labour party conference in Blackpool, 29 September 1975. Photo: Frank Barratt/ Keystone/Getty Images. 25 Taylor, Provos, 124–31; J. Haines, The Politics of Power (London, 1977), 132–33, 146. 26 Coogan, The Troubles, 207. 27 Haines, The Politics of Power, 115. 28 Harold Wilson to Merlyn Rees, 22 October 1974, Prem 16/151, UK National Archives. 29 Minutes of IRN (75), Cabinet Committee on Northern Ireland, 24 September 1975, CAB 134/3921, UK National Archives; emphasis added. the Wilson government, Haines stated forthrightly, ‘England has only one more role to play in Ireland, and that role is her withdrawal from it’.27 Wilson’s interest in withdrawal remained strong throughout 1974. In October of that year, for example, as contacts with the Provisionals intensified in the approach to the ceasefire, Wilson wrote to Rees: I have been turning over in my mind the proposal I made in my speech on 25 November 1971 [the fifteen-point speech] ... I think there is a strong case for reviving this idea at the right time ... very fundamental decisions may have to be taken, requiring the assent of the whole House of Commons.28 Even during the dying stages of contact with the IRA in late 1975, when the British government had supposedly moved entirely to a policy of outright deception, Wilson regularly returned to the theme of withdrawal. In September 1975, for example, Wilson summed up a meeting of the Cabinet Committee on Northern Ireland, at which withdrawal had been presented as unfeasible, in the following terms: there [were] signs that popular feeling in Great Britain was turning against the continued involvement of the Army in Northern Ireland ... Very early withdrawal, integration, and ... repartition had been shown in discussion to be unpromising but no option or scenario should yet be finally excluded from examination ... The implications of a gradual withdrawal from major responsibility for security in Northern Ireland might have to be considered, and variants of the option of withdrawal, such as the granting of dominion status to Northern Ireland, should not be ruled out in the long term.29 57 Field Day review By stating that it was ‘very early’ withdrawal, rather than withdrawal itself, that was ‘unpromising’, Wilson sought to keep the door open for ‘variants of the option of withdrawal’. Just a few weeks before British representatives held their final formal meeting with the IRA in early February 1976, Wilson wrote an ‘Apocalyptic note for the record’, in which he advocated that the British government make contingency plans in case of a renewed loyalist challenge or a breakdown of control, in which case ‘The only solution ... would be one or other variety of withdrawal, most likely taking the form of negotiated independence of some kind’.30 The message the Provisionals were getting in the secret talks, that the longterm preference of the government was for a form of ‘withdrawal’ and ‘disengagement’, accurately reflected Wilson’s persistent advocacy of this option, although it did not indicate that it was likely he would, or could, implement this option. And Wilson was not the only Cabinet member advocating various forms of ‘withdrawal’ and ‘disengagement’ in late 1974 and early 1975. When Rees was asked in August 1974 whether the British government planned to ‘disengage’, he replied: ... in the view of pulling out and let them get on with it — No. In the sense that I believe strongly that it is the people of Northern Ireland who must and will work out their own salvation — if that is disengagement, then the answer is yes. And I accept that in one sense it is ... I’m not talking about next week or the week after or even the next month ...31 Several weeks later Home Secretary Roy Jenkins stated at a government committee meeting that ‘he thought we would probably have to withdraw’.32 Crucially, however, these terms were attached to a range of meanings, with ‘withdrawal’ often being used to refer to the withdrawal of troops from the North. In this sense, even senior British military commanders 58 repeatedly advocated limited ‘withdrawal’ in 1973 and 1974, to allow the British army to meet commitments elsewhere. And ‘disengagement’ was used to refer to a range of options for creating greater distance and separation between the North and the British government. Thus, when MI6 agent Michael Oatley told IRA leaders at a secret meeting in early 1975 that the British were prepared to, or wished to, discuss ‘withdrawal’ and/or ‘structures of disengagement’, he was using terms that were regularly used in discussion and advocacy around the Cabinet table and in British policy and military circles. However, even in its strongest form, as the kind of constitutional separation advocated by Wilson, ‘withdrawal’ was never synonymous with Irish reunification. The version of ‘withdrawal’ most frequently canvassed in British government circles was a form of independence that would probably leave Northern Ireland linked to Britain in some way, and which had, indeed, strong attractions for many loyalists and unionists. The fact that the British government offered to discuss ‘withdrawal’ or ‘disengagement’, rather than ‘Irish unity’ or Irish ‘self-determination’, is an indication of the care it took to choose a form of words that was compatible with the options it was willing to consider seriously. The choice of terminology indicates a careful attempt to bridge the gap between the demand of republicans for a declaration of intent to withdraw and the very real willingness of the British government to withdraw troops and ‘disengage’ from the running of the North. Prior to this point, the Provisionals had insisted that they would not end their campaign until the British made a declaration of intent to withdraw. The British statement of willingness to discuss withdrawal is best understood as a formula that was necessary to allow the IRA leadership to call a ceasefire in 1975 and enter talks, given its prior demand for a declaration of intent to withdraw. 30 Harold Wilson, ‘Apocalyptic note for the record ­— for strictly limited circulation. No. 10 only and Sir John Hunt’, CJ4/1358, UK National Archives. 31 NIO Press notice, 13 August 1974, ‘Mr Merlyn Rees says not a “pull-out”’, FCO87/177, UK National Archives. 32 John Hunt to Harold Wilson, ‘Northern Ireland: future trends of policy’, 3 December 1974, Prem 16/158, UK National Archives. ‘Everyone Trying’ 33 Memo on IRA ceasefire from Merlyn Rees to IRN (75), Cabinet Committee on Northern Ireland, 18 February 1975. The talks held the promise for the Provisional leadership that the undoubted British interest in forms of withdrawal or disengagement might be reconciled with republican demands for self-determination and with loyalist and unionist preferences for a majority-rule parliament in Belfast. Given the extreme difficulty that republicans had had in extracting from the British even the slightest shift in their position during the secret negotiations that led to the ceasefire, it seems utterly implausible to suggest that they ever thought that this could by any stretch be deemed a certainty. The story of successful British deception has taken such a strong hold that even the most sceptical scholars of the period have not seriously addressed the question of whether the British government was prepared to make a declaration of intent to withdraw in the course of these talks with the IRA. If we accept the view that a ‘declaration of withdrawal’ was an item of faith in the catechism of a dogmatic republican movement, it would indeed seem implausible that the British government would have ever considered making such a declaration in 1975, or even have entered such a negotiation. But if we instead consider the declaration as a favoured item on a republican agenda, and therefore subject to negotiation, it becomes much easier to understand how and why the British government might have been prepared to devise a workable compromise on this point. In fact, Rees stated quite plainly to a Cabinet Committee meeting in February 1975 that he was prepared to move towards the Provisionals on this issue: The Provisionals will no doubt try to bring us quickly to discuss a declaration of British intent to withdraw. We must try to make them realize that this is in a sense an irrelevancy; it is their Protestant fellow-Irishmen with whom they must come to terms. But if the Provisionals are looking for a face-saving formula, I do not rule out the possibility that we could find a form of words which would be consistent with previous ministerial statements and not inflame the loyalists.33 The message is clear. A declaration of some kind was open to negotiation. Rees was willing to work towards a form of words that the Provisional leadership could point to as meeting its requirement for a declaration of intent to withdraw. It might be argued that the British government could never have found a form of words that the Provisional leadership would accept, but it is entirely unsafe to assume this. If we start with the assumption that both parties were seriously exploring the possibilities for a negotiated settlement, the issue of a declaration of intent to withdraw can then be viewed, not as an impossible and intransigent demand, but as a site of struggle and an issue for negotiation. The Provisionals were also demanding the release of prisoners and the end of internment; they also sought radical changes to policing. Maybe they would have completely rejected a negotiated agreement that delivered on all of these issues if it did not also produce a declaration of withdrawal made in precisely the terms that they demanded. Maybe, but it seems unlikely. Precisely because the Provisionals have been assumed to be dogmatists, the place of the declaration in these talks has been consistently misunderstood, as an always-impossible stumbling block. But it was not the rock on which the process foundered. The assessment that the secret talks were initially a genuine attempt to negotiate a settlement, while both sides simultaneously manoeuvred for advantage in the event of failure or breakdown, is supported by the fact of Wilson’s direct involvement and close interest in the talks. In the past few years new evidence of this has emerged, although the evidence is patchy because key records have not been released. Three files on Northern Ireland in the British Prime Minister’s office covering the early months 59 Field Day review of 1975 have been withheld from release, unusually for this file series. It seems certain that they relate to these talks. It has only recently become clear that Wilson was directly involved in the management of these contacts from a very early stage and that he carefully concealed them from other members of his government. Thus, when Oatley began his secret contacts with the IRA in 1974 and 1975, Wilson himself provided the authorization, and knowledge of the contacts was limited to Oatley, Wilson and a few senior civil servants, including the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Northern Ireland Office (NIO), Frank Cooper. Initially not even Rees was informed.34 According to one of those centrally involved, Wilson told Cooper, when he (Wilson) was approving these contacts with the IRA, that Cooper need not bother Rees with it because Rees had enough on his plate already.35 The secret contacts with the IRA thus originated as an initiative with the direct personal sanction of Wilson, initially bypassing not only the Cabinet but even the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. The Ó Brádaigh papers show that, according to the British representatives, Wilson was personally consulted on the details of the 1975 ceasefire arrangements. This seems entirely plausible. These terms were so sensitive that it is unlikely that Rees could have endorsed them without Wilson’s direct support. It may be that in agreeing these ceasefire terms, Wilson had stretched the British state to a position that went beyond what the security forces would accept. Given Wilson’s long-standing advocacy of forms of withdrawal, there seems little doubt that he was open to an outcome from these talks that went further than simply attempting to get the IRA quietly to accept the constitutional status quo. It emerged from the MI5 archives in 2009 that Wilson insisted that the Director General of MI5 report directly to him and to Rees on these talks and that he was not to report to Home Secretary Roy Jenkins. 36 This despite the fact that normal 60 procedure was for MI5 to report to the Home Secretary. These scattered pieces of evidence strongly suggest that Wilson looked on the talks with the Provisional leadership to a great degree as a personal initiative and that he maintained his interest in these talks primarily because of their potential to secure a negotiated peace settlement that would facilitate British disengagement and the withdrawal of troops, rather than as a ruse to weaken the Provisionals in preparation for a renewed drive for military victory. The extent to which Wilson was willing or able to implement a policy shift in this direction was, however, an entirely different matter. Republican Strategy A key element in the argument that the IRA was deceived is the suggestion that republicans took British talk of withdrawal as an indication that they had won the war and were now negotiating the terms of British surrender. As Smith puts it: ‘The Provisionals fell into the trap of believing that they had forced Britain into the ceasefire, and were, consequently, in a position to exact everything they wanted.’37 However, the British government and army assessed at the time that ‘hardliners’ in the IRA were persuaded to a ceasefire primarily on the basis that it would provide a muchneeded respite for an organization under intense pressure from the British army. 38 This picture of an organization under such pressure that even its hardliners calculated that the risks of a ceasefire were worth trading off for the benefits of a respite cannot be reconciled with the picture of an organization that believed it was in a position to exact everything it wanted from the British government. The former overestimates the importance of IRA weakness in motivating the ceasefire while the latter is plainly incorrect. Bew, Frampton and Gurruchaga come closer to a convincing explanation for the truce when they argue that it was prompted 34 J. Powell, Great Hatred, Little Room: Making Peace in Northern Ireland (London, 2008), 68. 35 Unattributable interview with former British official, 7 October 2008. 36 C. M. Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (London, 2010), 626. 37 Smith, Fighting for Ireland?, 130 38 Hamill, Pig in the Middle, 178.