Rear Admiral Philip Cullom

advertisement

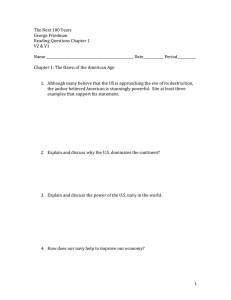

174 Rear Admiral Philip Cullom Senator, I am very humbled by that introduction. I would really like to start out by thanking The Honorable John Warner for his visionary leadership in this area. At a time when other people were Rear Admiral Philip H. Cullom graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy with a bachelor’s degree in physics and from Harvard Business School with a master’s degree in business administration. At sea, he has served in various operational and engineering billets. From 1998 to 1999, he commanded USS Mitscher (DDG 57). As commander of Amphibious Squadron Three, he served as sea combat commander for the first Expeditionary Strike Group (ESG 1) (2003–2004). From 2007 to 2008, he served as commander of Carrier Strike Group Eight. Ashore, he has served in various positions including shift engineer and staff training officer of the A1W nuclear prototype at the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory, special assistant to the Chief of Naval Operations’ Executive Panel (OP-00K), and branch head for Strategy and Policy (N513). Joint assignments have included defense resource manager within the J-8 Directorate of the Joint Staff, White House fellow to the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, and director for Defense Policy and Arms Control at the National Security Council. He also served as the head of Officer Programs and Placement (PERS 424/41N) from 2001 until 2003. After completing major command, he served as the chief of staff for Commander, Second Fleet/Commander, Striking Fleet Atlantic until 2005. Flag assignments ashore included Navy staff positions as director of Deep Blue, the Strategy and Policy (N5SP) Division, and Fleet Readiness Division (N43). In 2010, he assumed his present duties as director of the Energy and Environmental Readiness Division on the Navy staff. Rear Admiral Cullom’s awards include the Defense Superior Service Medal (two awards), the Legion of Merit (five awards), the Defense Meritorious Service Medal, the Navy Meritorious Service Medal (two awards), the Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal (three awards), the Joint Service Achievement Medal, and the Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal. Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 175 not thinking about this issue, he was doing so. He was able to garner support across the aisles—to identify and work with the people who could move this thing forward. I think we as a nation, and we as a Navy, owe an awful lot to Senator Warner for where we are on these issues today. So I would actually like to give a great round of applause for him because without his active involvement, our children, our grandchildren, and our great-grandchildren would live in a very different world. I have the unenviable position of being the after-lunch speaker which, as you all know, is a hard slot to fill because the audience is oftentimes tempted to let their minds wander. So I am going to try to keep us on track, adding a bit of variance to my standard PowerPoint brief. I am going start out with a video that will capture our imagination about how important this issue really is. Figure 1. Easter Island In the past, when I have talked about this, I have done so using a couple of slides. I think they were powerful, but I think I am going to let the experts speak to this. These particular experts were picked by the History Channel for a program that first aired about 176 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 2.5 months ago. It has been shown several times since then. This very powerful program features five futurists, brought together by the History Channel, to talk about potential global events that would present the greatest challenges to mankind. Now this is not the first time that something like this has happened in the world. Oftentimes people say that history does not necessarily repeat itself, but it does rhyme. Well, one of those rhymes is Easter Island. A thousand years ago, Easter Island was the site of a pretty advanced society for its day. It was founded on the island’s major resource, which was wood, timber. As you can see from Figure 1, there is not much wood on Easter Island today. It is all gone because they used it and never replaced it. Eventually, by at least some reports, they chose to resort to cannibalism in their attempt to stay alive. So when we think about where societies have been through time—and Easter Island was not the last one that got into trouble, there have been others that have followed a similar rhyme or theme—we need to think about where we are today and where we are going. I am going to start by saying that we are faced today with a number of different paradoxes, laws, and maybe corollaries to those laws. Figure 2. The Jevons Paradox, Moore’s Law, and Energy Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 177 The first one I want to bring up is called the Jevons paradox (Figure 2). Jevons was an economist in the United Kingdom back in the mid-19th century. You can see some of the things that he observed as the British economy at the time was dealing with the depletion of coal in England and Wales. What he saw was that as machines became more and more efficient, the operators tended to consume more and more fuel. That, in turn, meant that the mines were being depleted that much faster, despite the fact that things were much more efficient. Fast forward a century or so to the mid-1960s when another individual, Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, came up with his law, which was that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit board seemed to double every 2 years. Almost everyone remembers that part. He also said that with that doubling, your power requirements also doubled. There is some debate today regarding whether Moore’s law is still in effect or whether it may eventually reach a peaking point, which would have its own interesting dynamic. But certainly what we see today and what we saw in our own military as we went from sail to coal to oil is an example of both the Jevons paradox and Moore’s law. Back when we had sail as our only energy source, we were a pretty self-sufficient Navy. We had manpower and we had wind, and the only other energy source was the whale blubber that we used to light the smoking lamp, which then either got used for smoking or for lighting the cannons so that we could destroy the enemy. We foraged for water and food, and that was about it. By the time we moved into the 20th century, we found that we had this seemingly inexhaustible source of cheap power, and that inexhaustible source of cheap power meant that we could live in a profligate manner and not have to be austere or Spartan in any way. We just shoved everything off on the logisticians. We told them to just figure out how to get the oil there, and we will do the warfighting. With that has come a vulnerability. We understood that in World War II. We understood that the U-Boat attacks, in part, were about destroying those logistic links across the oceans. Sadly, we 178 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 have had to relearn that lesson on today’s battlefields in Iraq and Afghanistan. Lest we not have to relearn that lesson at sea, I think it is important for us to make sure that we address both these trends and find a way to keep the march of technology and our improved efficiencies from simply requiring more and more energy. What we really need to become is a smart Navy—a smart Navy that really is an austere, energy-efficient Navy (Figure 3). Because if we are energy efficient and energy smart and have that Spartan mindset to be able to sustain our mission, we will be able to operate, if we pick the right energy sources, in perpetuity. That is an important piece of this that I want us to understand as we reflect on what happened on Easter Island. We have to be able to do this in perpetuity, both as a military and as a nation and as a globe. Without that, at some point the gig is up, and at some point it comes to an end. We have to decide whether we want our society and our world to continue in perpetuity. I have to worry about making sure that our Navy is able to continue its operations in perpetuity. Figure 3. An Energy-Smart Navy To do that, we need to focus on energy efficiency when we acquire new systems and platforms. The things that we build for the future need to be as efficient as possible, so that our new ships and our new planes really are austere in the way they are designed and built. At the same time, we have to improve our Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 179 existing fleet efficiency. We have to make sure that the Navy that is out there today is as efficient as it can be as well, even though it was designed when the cost of a gallon of gas was probably less than a dollar. We have to find diverse energy resources, and then ultimately we have to change our behavior. Otherwise, as Jevons showed, we will continue to use more and more energy, even as we make our systems more efficient. So, changing our behavior is ultimately how we get to an energy-smart Navy. And if we have an energy-smart, sustainable Navy, you can use the same lessons and extrapolate those to an energy-smart nation. Let us turn now to the topic of energy efficient acquisition (Figure 4). Earlier this morning, the Vice Chief of Naval Operations talked about acquisition related to climate change writ large. The lessons that we have learned on the energy side of the house are very similar. While we have been embarked on the journey of trying to get to energy efficient acquisition for a couple of years, we have more work yet to do. It is pretty clear where the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff stands on this issue. Figure 4. Energy Efficient Acquisition As some of you may already know, acquisition is a difficult process, and unless you are in the acquisition world and trained as 180 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 an engineering duty officer, it is a hard thing to understand because it has a lot of moving parts. You have milestones A, B, and C. You have a process with different steps along the way. You have gate reviews that have to happen at certain points and times. And you have this Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System (JCIDS) process that is used to define the requirements for the thing that you are going to build, whether it is a plane or a ship, and the capability that it will need to have when it is finally delivered to the warfighter. Now we oftentimes think that we can solve this problem simply by defining the right Key Performance Parameter (KPP) or the right Key Success Attribute (KSA). But the reality is that if we are going to do this right, we have to tackle it in two ways—the process and the paradigm. You have to start as early in the process as you can. You cannot wait for a gate 6 review to say, ”You know, we should have made the system more energy efficient because you have already expended hundreds and hundreds of thousands of man hours to create the energy-inefficient platform now in front of you.” We have to identify and define the right attributes very early in the game. The Marine Corps and the Navy are in synch on this. I have spoken with their Expeditionary Energy Office, and we are approaching this in exactly the same way. We both want to start very early in this process and make sure that, in the gate reviews along the way, we can ensure that what we are doing, and what we actually are building, is in fact energy efficient. Now how do you do that? It is always a matter of trade-offs. Just like in the space program when you build a satellite, you have to worry about payload. You have to worry about the energy that it uses once it is up there and the capabilities that it needs to have. You need a lot of scientists and engineers sitting around a table to figure out what trade-offs must be made to ultimately produce the satellite that can do the mission. The problem is that we do not normally do that when it comes to building ships or planes. The paradigm we tend to use for our military systems starts with some desired capability or capabilities and then translates that into specific requirements. For example, you might want to be able to hit a pea that is going Mach 5 at Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 181 500 nautical miles, which will require X amount of energy. That requirement is then handed over to a team of engineers who are responsible for one particular aspect of the design, say the propulsion system. When they have done their job, they kick the task across the transom, across the fence to the next guys in line. The next engineer says, “Okay, well, then you need a 10-megawatt generator,” and that in turn goes on and on and on. Ultimately we end up with a ship or a plane that is significantly different than what it would be if we had forced everybody to sit at the table and balance the capability requirements with the operational energy requirements as part of an analysis of alternatives. All of the necessary trade-offs would be made as a part of this process. We need to figure out what to put into the process—how to change the paradigm so that the analysis of alternatives is not on the outside, but on the inside. If we can do that, then we can fundamentally change what we build for the future. That is part of our challenge. It is not an easy thing, and the joint world has to be involved. Retooling the existing fleet—or said differently, fixing a fleet that was designed very inefficiently from an energy perspective—so that it becomes a fleet that is much more efficient for the future is a task that we have been embarked on since we kicked off Task Force Energy several years ago. Many of the ships we have today will still be in the fleet in 20 or even 30 years. The life span of a destroyer is 40 years. The operational life span of an F/A-18 is 10,000 flight hours (and we typically fly 400 hours per year). Because we will own these things for a long time, we better make them as efficient as we can along the way. So what are we doing in that regard? Over the last 2 years, we have been focusing on making what is out there today as efficient as we humanly can (Figure 5). We are installing efficient lighting systems that will also last a lot longer without having to be replaced. We are improving hydrodynamics by adding stern flaps and using hull coatings and propeller coatings that improve laminar flow across the hull and save a percent here and a percent there. It may not seem like a lot, but those percentage points add up to 182 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 millions and millions of dollars in savings. Installing a hybrid electric drive system on a DDG-51-class destroyer will save 8500 barrels of fuel per ship per year. We are also changing the way we operate our fleet. Part of this is actually cultural in nature, but save that thought, we will get to that later. We are making use of the predictive capabilities that our oceanographers provide by making sure that we sail our ships along the most fuel-efficient routes and thereby reduce our fuel consumption by a few percent. Figure 5. Maritime and Aviation Technology On the aviation side, we are conducting research and development on engine modifications that we can make to the F/A-18’s gas turbine, which in turn can ultimately be rolled back into the engine on the F-35. We are looking at new science and technology for the variable cycle engine. This one is a little bit farther out there, but we have got to be thinking continually ahead of the problem. If we are ultimately going to make some of these things a requirement, then we have to make sure they are included when we write the Initial Capabilities Document (ICD) or the Capability Development Document (CDD). That in turn will enable the Office of Naval Research to develop the appropriate technologies so that our industry partners can deliver a product 10 years from today Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 183 that is significantly different in terms of its energy efficiency. That improved efficiency will also enhance our combat capability by expanding our tactical reach or extending our endurance. On the expeditionary and shore sides of the house (Figure 6), we are involved in a similar game. We are focusing on creating a Spartan warrior ethos that will drive us to make austere use of our energy in the future. India Company of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment was provided with several energy-efficient systems during their recent deployment to Afghanistan. In the process they have learned that they can use the new technology in ways that they probably would not have predicted before they took it out there. Figure 6. Expeditionary and Shore Technology We are also experimenting with a number of different kinds of power sources. In some cases you just roll them out—they are actually on a fabric. You can put them on the top of tents, making those tents more energy efficient as well. We are working with the Army on that one. Onboard vehicle power is another very important way to make the engines that we are using more efficient. The Marines are going to be experimenting with such concepts during this summer’s Expeditionary Forward Operating Base (ExFOB) event. 184 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 On the shore side, we are working hard to make our buildings and installations more energy efficient. At the same time, we are looking at ways to incorporate renewables so as to make ourselves more sustainable. This will enable our critical infrastructure ashore to continue to support the mission in perpetuity. We are also working to change Navy culture and behavior by providing more transparency in how our individual commands and functional levels use energy. Ultimately, we want to enable those organizations to adopt appropriate energy efficiency technologies. Let me shift to diversifying our energy resources. The Secretary has spoken very passionately about this and about why we need to it, not only as a Navy, but as a nation. Figure 7. Alternatives—Diversifying the Fuel Mix But let us take a look at this from the technical perspective of what we have to do. Figure 7 shows the fuel mix that we are using today. Unfortunately, we have created this chart based on percentages, so all the bars have the same height (i.e., they add up to 100%). But if you look at it in terms of the amount of energy provided, the afloat pillar would be three times higher than the ashore pillar. Do not let this fool you into believing that all we have to do is solve the afloat side. That is not true. We have to tackle both the afloat and the ashore portions, particularly given our shore side’s heavy reliance on the commercial power grid. Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 185 The right-hand side of Figure 7 shows where we are going and the diversity that we expect to have. That diversity will buy down our risk. It will buy us confidence that, if at some point we were to lose one of those pieces of the mix, we would not be held hostage to that loss and that we would be able to continue our mission. And, as you can see, we also intend to diversify the fuel mix used on the afloat side. Figure 8. Alternatives—Test and Certification Milestones Relative to where we were a year ago, we have accomplished a lot in the last 12 months (Figure 8). We have flown an F-18—the Green Hornet—on alternative fuel. We have also demonstrated use of alternative fuel on the Experimental Riverine Command Boat (RCB-X). We have flown a helicopter on alternative fuel. Keep in mind that these are drop-in replacement fuels, and this gets to one of the questions that was asked at the beginning of the morning. We are not out here trying to invent a whole new logistics system to handle a different fuel. We want these fuels to mix in seamlessly with the petroleum that is already there so that you do not have to have a whole separate logistics system to handle that. That way, no matter where you are, you will always have access to fuel of whatever kind, whether it happens to be a biofuel or it happens to be distilled petroleum. Obviously, the quicker and faster we can move toward those alternative sources, the better off 186 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 we will be from a sustainability standpoint and from a greenhouse gas standpoint. Earlier, someone asked whether we would be able to achieve the alternative fuel goals we have set for 2012 and 2016. I firmly believe we will be able to make it, and we now have some pretty good work that is being done by industry, independently from the Navy. Indicators are that industry will be able to support our goals for 2020, which call for use of 50% alternative fuels by that date. I call this Cullom’s Corollary: For the foreseeable future, we will not be able to get away from use of an energy-dense liquid fuel for airplanes or for ships at sea. You need an energy-dense liquid to move those large things. Now is there going to be something different in the distant future? Probably, and we have to look for those things; we have to look for those generational leaps. In the meantime, we better have something that can meet our needs for the next 20, 30, or 40 years. Fortunately, we are not the only ones thinking about that. The commercial airlines and commercial shippers are all looking at exactly the same series of things and realizing that we have to have a solution set for the long haul. Right now, we are testing the use of our biofuel blend on one of our older engines, the Allison 501, which is the precursor to the LM 2500. The LM 2500 is the big gas turbine that we use on our frigates, destroyers, and cruisers. So once we finish the test on the 501, we will have certified that all of our engines are able to run on 50/50 blend mixes of drop-in replacement fuels that look, smell, and act like any other petroleum fuel. Their origin, however, is decidedly bio. Last, but not least, and probably the hardest one of these things, is culture and behavior. The Chief of Naval Operations has said it very well. We realize that we have been wedded to gas, and you cannot get away from that. He had his air controllers think about that every minute, because you need to know how many pounds of fuel that F/A-18 on a combat air patrol station has. Frankly, it is no different for our ships at sea. The captain gets briefed every Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 187 8 hours on the fuel percentage remaining and where and when the next refueling will be. Those things are never far from your mind. Figure 9. Culture Change—Sample Fleet Initiatives In addition to culture and behavior, we are working hard to change the technologies that are available to us (Figure 9). We are working on a diverse set of technology initiatives that you will see play out over the next 5 years. Adding those changes to the culture piece really makes the return on investment much larger than what was originally expected. Use of hybrid electric drive on destroyers is expected to save 8500 barrels of fuel per ship per year. What if we coupled that with a box placed on the ship’s bridge—like the one you might have seen on the Prius—that shows your fuel efficiency continuously? That sort of thing can change your behavior. So, our plan is to have that device on the bridge of a destroyer in the not-too-distant future. It will help us run our ships more efficiently. However, if your combat requirement imposes a need for speed, you will still have that to use. But there are times you do not need speed—and there are many times that you have your ship out there and it only needs to do 6 knots—such as when you are waiting to shoot Tomahawk missiles, when you are patrolling a sector looking for pirates, or when you are offering help and assistance 188 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 in response to a disaster. It is during the times when logistics lines may not be there for 3 or 4 days that these efficiency initiatives will really pay off. We recognize, though, that speed is still important, so we are proposing to put speed and efficiency together, to provide a force multiplier. The Navy’s Pacific Fleet is working on a number of energy efficiency improvements. In fact, they have set up what they call the Expeditionary Naval Operating Base. In analogy with the Marine Corps’ ExFOB, we might call it the “ExNOB.” It includes the ships as well as the base and infrastructure at Pearl Harbor. Some of that is a matter of the tyranny of distance. The Pacific Fleet has to worry about that because the distances are much longer out there than is typically the case in the Atlantic or the Mediterranean. So, the Pacific Fleet is looking at fleet initiatives that they can test and prototype and that will ultimately find their way into the rest of the fleet. The rest of culture change really is across the board. We need to provide energy-related training so that everyone understands the issues, from the seaman recruit to the Chief of Naval operations and all the people in between. We need to provide incentives to our personnel and establish subspecialty codes that will identify personnel who have expertise in climate or energy issues. We need to make energy efficiency one of the factors we consider when awarding unit incentives. Many Navy personnel here wear a battle efficiency award. Most of us do so proudly, because it takes an awful lot to get a Battle “E.” Right now energy is not a part of that, but why shouldn’t it be? If that truly is part of our warrior ethos, truly part of being a Spartan warrior, why shouldn’t we take it into account when we make awards for being the best ship, the best aircraft squadron, the best shore command, or providing the best infrastructure support? We have also talked about redefining the process, bringing all the right people to the table. While that will be very difficult, it is part of the cultural change that we have to continue to work toward. But austere energy frugality really is just a return to our roots. If you have a chance to tour the USS Constitution and walk Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 189 the decks, you will certainly see that frugality was very much the mindset of that day. Our challenges are many (Figure 10). Earlier this morning, we heard about the volatility in the cost of energy, particularly oil. Right now it seems that the price of crude is going up and up and up, and we are getting whip-sawed more and more. Figure 10. Our Challenges There are a lot of energy alternatives out there, but a lot of the technology is immature. So, we need to make the right bets. What things do we choose? What do we send through operational test? What do we experiment with so that we are sure that we chose the right things? We are, in fact, experimenting with a number of things that have been part of our plan over the last couple of years. We will have to see how things like ocean thermal energy conversion, wind, and geothermal play out. The choices we make on the infrastructure side can also help make us a much more resilient Navy in the future. I cannot finish my presentation without talking about total ownership costs. If we do not keep an awareness of this, we are 190 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 certain to have problems. The cost of energy is currently rising five times faster than the overall consumer price index. Manpower costs are rising at twice the rate of growth of the consumer price index. While we often think of manpower as being expensive, the cost of energy is going up much faster. Sooner or later it will eat us out of house and home. If you are spending more for energy, it means that you are just going to spend less for something else, whether those things are beans, or bullets, or ships, or planes. And at the end of the day, how do you do pay that energy bill and still be able to keep the capability and readiness of our force where it needs to be? Those are the challenges. As I have said, we are in the process of changing paradigms. We are moving toward diverse energy resources, toward making the existing fleet more efficient. We are trying to get energy efficient acquisition established, and we are trying to change culture and behavior. Our goal is to reduce our energy consumption to sustainable levels, and by doing so, gain tactical advantage. Changing the efficiency of the existing fleet is not very sexy. It is only a percent here, a little percent there, but this is where combat capability comes from, and this is why we are working on it so hard. If we do not solve these things, we will never get to a sustainable force. I want to leave you with two thoughts: the first is that this journey that we are on is not an easy one. It is hard; it is one that will take far longer than any one individual’s tenure. It will take longer than the careers of the lieutenants who are working on this, or the youngest engineers and scientists. We will still be working these issues when you are my age or Senator Warner’s age because that is what it is going to take. It is going to take the dedication of all of us to reach this. My second thought is that energy, and sustainable energy in particular, is linked to climate. Both Rear Admiral Titley and I talk about these two issues being two sides of the same coin. The word is “anthropocene”—a term that was coined by Dr. Paul Crutzen, a Dutch chemist who won the Nobel Prize. About a decade ago, he said that we are in a new time epoch that is defined by our own massive impact on the planet. Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 191 Scientists believe that the Anthropocene epoch (Figure 11) is characterized by changing seas, urban super sprawl, and planet resource limits (in terms of both energy and water) and by what I would call the perfect trifecta. The first element of that trifecta is a population which, at about 7 billion people, is well beyond the burden-bearing limit of the planet. When we were relying on coal, the population was about 2 billion people. What is that burden loading of the planet going to be if oil goes away and we have not found some kind of a substitute for it? Figure 11. Do We Live in the Anthropocene Epoch? The second and third elements of that trifecta are affluence and technology. Everyone wants to be more affluent, and everyone wants to use more technology. The impact of those two factors in the face of continued global population growth is what makes this the Anthropocene epoch. Bill Gates talks about this, and he says it much more simply. He says, “Look, we have a planet ‘A.’ We do not know where planet ‘B’ is or even if it exists, so we better make planet ‘A’ work. And making planet ‘A’ work had better take climate change and energy into consideration.” You pretty much cannot talk about where our future is going without realizing that it is going to be ever more constrained in many, many dimensions. And it will be constrained for the Navy, it will be constrained for the nation, and it will be constrained for the globe. 192 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 I am going to end my remarks with the photograph below and by doing so bring my talk back to the sea. As I am sure Rear Admiral David Titley will point out tomorrow, ocean acidification is the silent partner to greenhouse gases. And guess where that acidification comes from? CO2. The same CO2 that is causing the rise in global temperatures. So if we do not want the planet to look like this by 2100, then we better start doing something different, and we better understand what the Anthropocene Age really brings us to and what changes it will wreak on the globe. That is why we need to come up with a coordinated plan, a holistic plan that looks at these issues together. Why is that so important? Because the carbonate that is available for the growth of coral is not just available for the coral, it also supports algae and all the living things in the sea. The bottom line is that if you kill the coral and you kill the algae, you kill the entire ocean ecosystem. If you kill the ocean ecosystem, not too many people are going to be able to live on this planet given that the oceans cover nearly 70% of the Earth’s surface. Hopefully that brings us full circle. Doing what is right for the Navy, making a sustainable Navy, can help lead the way to a sustainable planet at the same time. REFERENCE 1. Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Viking, 2005. Q& A Session with Rear Admiral Philip Cullom the late 1800s, the United States did not have any of the Q: Inarmor plate needed to rebuild its iron-clad fleet. Therefore, the Navy put out a specification for armor plate. Andrew Carnegie picked that up and produced the armor plate needed to build the Great White Fleet. Do you see industry responding in a similar way to the Navy’s need for biofuel? Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 193 Rear Admiral Philip Cullom: Yes, they are. Actually, that is part of what the 2012 and the 2016 timeframes are all about. Those events will create specific demand signals that are not related to some uncertain future increase in the price of oil. If that were the case, we would have to wait for some venture capitalist, some angel investor to say, “Yes, there is a market out there.” Right now, however, everyone is looking to the DoD to provide that first entry point. We need 8000 barrels of biofuel by 2012. So, the demand signal is going to be out there very soon for people to bid on. By 2016, we will need 80,000 barrels, and by 2020, if not earlier—and my bet is that it will be earlier because I think the cost parity point will occur before then—we will need 8 million barrels. We believe that is the only way you can get the diverse mix that you need to buy down our risk as operators, as warriors, in going out there and doing our mission and not being held hostage to whether or not the price of a barrel of oil is $150 or $300. So we are sending some very strong signals. We are also making some rules change, and Congress has taken leadership in this arena by stretching out the contracting ability for the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) so they can have 10-year contracts for certain things, rather than just the standard 5-year contracts. Such incentives provide strong signals to the angel investors, the venture capitalists, and others, so that they will have the confidence to say that it is time to pour money into XX company because they have a good process. As we all know, there are going to be winners and there are going to be losers in that process. I would like to see a lot of winners, and I would like to see a lot of winners in the United States of America. explained how the Navy’s need for 80,000 barrels of bioQ: You fuel will serve as a demand signal that might draw investors. What sort of metrics have you been using to see how that is progressing? As a follow-up, I would like to know if the Navy is partnering with others, perhaps commercial or other services, to create these demand signals? Rear Admiral Philip Cullom: I will respond to your questions in reverse order and cite some of the other folks who we are working with. Key among these are the shipping industry—UPS, FedEx, 194 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 and the Postal Service, as well as a host of others—along with the commercial airlines. These firms are large enough that they can send their own demand signals. I think we will probably see that very soon. There is actually a consortium of companies and organizations, some of whom actually work with DLA, that is looking hard at where the market is going. We also have partnerships with academia. At our request, MIT’s Sloan School of Management sent a team out to look at the biofuels industry and where it is going. They went and talked with angel investors, with venture capitalists, and with manufacturing companies, both large and small, that are either developing or already delivering real product for customers, to include the Navy. What we learned from that task forms the basis for my feeling infinitely more certain today than I did a year ago as to whether or not we are going to get to that parity point. We have also worked with DARPA, with the Office of Naval Research, and with others who are also looking at this. The Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency– Energy is also looking at some of these issues, and we are plugged into every one of those efforts and understand exactly where they are going. The Honorable John Warner: Could you address the concern that biofuels take valuable farmland out of food production and use it to grow crops that provide fuel? Rear Admiral Philip Cullom: That question comes up an awful lot, and it is a logical question to ask because there are a lot of people out there who say that if you want to supply all of the nation’s gasoline demands with biofuel, you are going to have to cover 15 states with camelina, switch grass, or something else. And you know what? That is correct. But we would never do that. That is why I was pretty careful about my corollary that on the aviation side and on the ship side, you cannot get away from an energy-dense liquid fuel. In the case of cars and trucks, however, we ought to have our heads examined if 10, 20, or 50 years from now, we are still fueling them with gasoline. They should be Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 195 running on electricity, fuel cells, or something else because they can and they can do that as cheaply, probably, as anything else. I do not want to get into the national policy on that; that is not my gig. But I think that we are seeing that play out in front of our eyes today. I do not think you need to worry about the massive amounts of energy that goes into the transportation industry except that used by planes and ships because I think they will stay on liquid fuels for some time to come. Our problem now is significantly different and significantly reduced. There are ways to be able to pursue our fuel goals so that you are not actually going after farmland in Kansas. Or if you do, you go at that farmland in a way that actually increases or improves the yields. I come from a pretty small town in Illinois. The field next to our house was filled with soybeans and corn. I will neither confirm nor deny that we ever took an ear of corn out of there. The bottom line is, farmers had to rotate the crops and they had to fertilize them to make the crops grow. One of the good features of some of the energy crops like camelina is that you can actually plant it in between crops of corn. Maybe you do not get quite as many ears when you do that, but you are replenishing the soil with nutrients without having to fertilize it. There is huge benefit in that, because most fertilizer comes from petroleum or from other fossil fuels. There are ways to make the whole process much more holistically energy efficient and not disrupt the food chain. I might add that one of the other partnerships that we have embarked on is a NASA project called Omega. The project deals with being able to take treated sewage that normally just spills out into a bay, putting that sewage into polyurethane bags, and towing it into an area where it can sit offshore and flop around for a while. Prior to doing that, you inoculate it with algae, and 7 days later, plus or minus, you get oil out of it. It is a pretty good way to turn waste into energy using something nobody else wants. Moreover, this approach does not use any land whatsoever, although it will use some littoral areas. We have looked at the environmental issues associated with it. It uses freshwater algae, 196 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 so it dies if the bags break open while it is in saltwater. It does not disrupt the ecosystems in other ways either. So, we now have a Navy–NASA joint partnership—just one of many that we have set up. I think there are ways that we can smartly do this so that it does not impact the food chain or food prices or result in any of the negative things that we saw happen with corn. could you highlight some of the opportunities for collabQ: Sir, orating with international partners or foreign governments? Rear Admiral Philip Cullom: The Navy frequently works with many partner nations and partner navies around the world; we are seeing that play out right now off the coast of Libya. It is important that we be able to truly help each other when we are out at sea because the sea is a pretty unforgiving environment. It is also pretty important from an energy perspective. That is one of the reasons that we have been in touch repeatedly with not only the folks here in town, but also with each of the combatant commanders. We have asked them to bring people together to talk about both climate and energy. I was lucky enough to get invited to Lima, Peru, to talk with our South American partners about energy issues as part of one of these climate and energy forums. I think that it is critically important to have such dialogues so that we can understand that we need to work on these things together. This is particularly true on the fuel side with these 50/50 drop-in replacement blends. The results from these tests should be shared with our partners so they can take advantage of them as well. As many of you may know, the Allison 501 generator is actually a Rolls Royce engine, which is used by a number of our allied partners. A number of nations use the same fighter aircraft that we do. Several will eventually end up having the F-35. The things that we are doing in preparation for the F-35 will have huge applicability for the navies and air forces of our partners. Chapter 6 Task Force Energy Update 197 have heard a fair amount about the benefits that the Q: We Navy can expect from improving energy efficiency. Can you address the consequences that might be attendant to energy efficiency that the Navy might want to consider? Rear Admiral Philip Cullom: In my view, it is a combination of both consequences and risks. When we shift over to alternative fuel sources, we want to know, to the extent possible, whether there are things that we did not predict that may now rear their heads. Fortunately, we can learn from history because the Navy has transitioned from wind to coal to oil. And, although history does not repeat itself, it does rhyme. We certainly saw that as we transitioned from coal to oil. We had coaling stations in various places around the world. When we shifted to oil, it suddenly meant that we needed some different things. For one thing, oil is more energy dense, which gave us longer legs. It also meant that we had to store our petroleum fuels in different areas than we had previously thought about. That, in turn, caused us to rethink a number of things that had strategic, operational, and tactical consequences. Fortunately, transitioning to biofuels will be a bit simpler, because we are not transforming to a radically different kind of fuel. It is still a liquid fuel; in fact, that is precisely why we went to drop-in replacement. We could have chosen other possible biofuels or other alternative fuels that would have forced more radical changes. Had we done that, we would now be forcing ourselves to totally reinvent our logistics train. We would have had to build new oilers, new transfer rigs, and separate fuel storage tanks. We thought about all of these things as we went through this. If we are going to diversify our mix, how do we do that at the least overall cost? We also want to have flexibility so that if at some point there is a blight of whatever and the crop of a certain type of algae does not produce, or the price of camelina goes up, we would be able to weather through such events by reverting to regular petroleum. Our mix could go from 50/50 to 80/20 for a year or so. Our overall 198 Climate and Energy Proceedings 2011 intent, though, is to push toward a more sustainable alternative mix that, over the long term, does not need to be mixed at 50/50. We do not want to have too much risk in the near term, so we have tried to constrain the rate at which we are changing technology. We are managing the risk by going 50/50. We think this imposes minimum risk and will enable us to transition to alternative fuels. We will continue to work on the science so that we can get to the perfect blend of a true alternative fuel that is a 100% biofuel. If we had gone to that first, 2020 would have been a pretty far stretch. We are trying to mitigate some of those risks. Are there going to be other risks that are associated with some of this? Yes, and that is one of the reasons why we need to partner with industry, because they are looking at all these risks as well. Understanding what their risks are helps us understand what our risks will be in moving toward some of these same goals, whether it be at the Office of Naval Research, DARPA, or elsewhere. And let me also make note of—and this goes back to Senator Warner’s question—some of the places where these alternatives can be grown. I will speak to algae. I had the good fortune to go out and kick the dirt at one of the places where they are building a production site. The farmer who sold the land to the company said: “You know, you cannot grow anything in this stuff. I feel kind of embarrassed selling it to you, but if you want to buy it, I will. I grew corn up until 3 years ago and now there is too much salt. You cannot grow anything in it now.” In other words, this particular project was not taking land away from anyone. But guess what? They needed saltwater because that is what they were going to grow their algae in. And they needed a renewable source so they would not end up taking too much of the water out. Companies are thinking about these issues. That is a way of mitigating risk as well. But that is also a way of not having to impact good crop land that needs to be used to grow food, for us and for the world.