The Application Process For TANF, Food Stamps, Medicaid and SCHIP

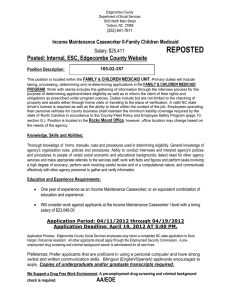

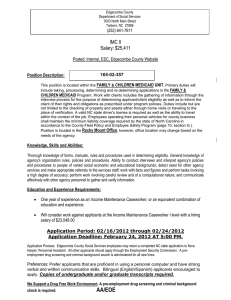

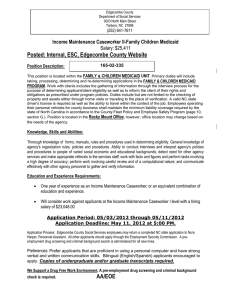

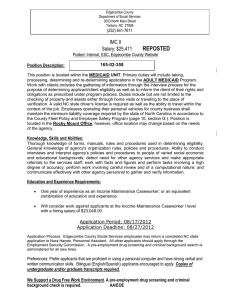

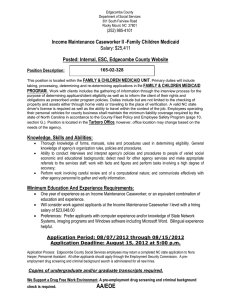

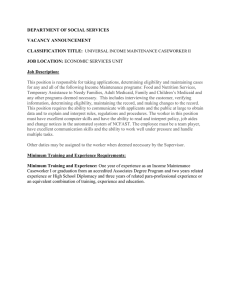

advertisement