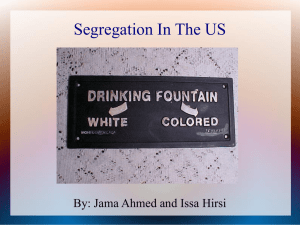

School Segregation under Color-Blind Jurisprudence The Case of

advertisement