Cost V Understanding State Variation in Child

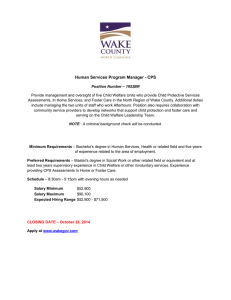

advertisement