Document 14819383

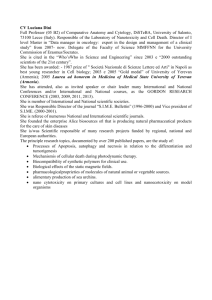

advertisement