MADISON PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT Third Grade Literacy Curriculum

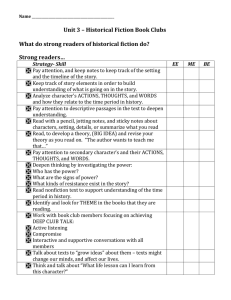

advertisement