On bayesian design in finite source queues ∗

advertisement

On bayesian design in finite source queues∗

M. Eugenia Castellanos1 , Javier Morales2 , Asunción M. Mayoral2 , Roland Fried3 ,

and Carmen Armero4

1

2

3

4

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Madrid, Spain maria.castellanos@urjc.es

Universidad Miguel Hernández, Elche, Spain j.morales@umh.es,

asun.mayoral@umh.es

Universidad Carlos III, Madrid, Spain rfried@est-econ.uc3m.es

Universitat de València, Spain Carmen.Armero@uv.es

Summary. We develop a Bayesian analysis of queueing systems in applications of

the machine interference problem, like job-shop type systems, telecommunication

traffic, semiconductor manufacturing or transport. Bayesian guarantees of system

performance can be given using the predictive or the posterior distribution. While

these distributions can be obtained by standard Monte Carlo integration in case

of an M/M/c//r queueing system with exponential operational and service times,

more refined Monte Carlo sampling (MCMC) strategies are needed in general.

Key words: machine interference problem, queuing design, Bayesian performance

criteria, MCMC methods

1 Introduction

Queueing models allow to analyze problems which involve congestion. Once the

characteristics of the system have been identified, we can derive conclusions about

its temporal evolution and steady-state behavior, sometimes analytically, mostly by

simulation [K75], [K76]; [GH98]; [LK00]; [M03]. Statistics becomes important in the

presence of uncertainty about the stochastic model. Bayesian inference is well suited

for analyzing queues because we can evaluate posterior and predictive distributions

for system performance measures taking different sources of uncertainties into account. Moreover, the Bayesian approach provides an optimal decision framework for

design purposes since incorporation of losses and costs is straightforward [AB99].

In an M/M/c//r queueing system, we analyze a set of r machines, which are

subject to failures and maintained by c repair crews. The Bayesian framework allows

us to derive performance criteria concerning the availability of the machines, without

needing to specify values for unknown model parameters. The queuing system can

thus be designed choosing a suitable number of repair crews such that a certain

acceptable system performance is achieved, with guarantees optionally in terms of

∗

Research under grants MTM2004-03290; GV05/018; TSI2004-06801-C04-01;

MTM2004-02934.

1382

M. Eugenia Castellanos et al.

the predictive or the posterior distribution. We discuss such criteria and illustrate

them on simulated data.

Section 2 presents the basic model and criteria measuring system performance.

Section 3 develops Bayesian design strategies guaranteeing reliable performance and

exemplifies our proposals. Section 4 presents some extensions of the basic model

needing more refined computational techniques.

2 Problem formulation

2.1 M/M/c//r queueing system

We start with a very simplistic model for illustration. Assume that a company uses r

identical machines for production. The machines break down at random time points

and must be repaired (maintained). The number c of repair crews needs to be chosen

sufficiently large to guarantee a satisfactory availability of the machines. A high

availability can be achieved by a huge choice of c, but for the prize of large costs. We

assume a unique type of maintenance service, discarding different kinds of damages,

inventory limits and transportation times. Section 4 presents some extensions of this

basic setting.

In the language of queueing systems, the machines act as users and the crews

as servers. When an user arrives at the system and finds an idle server, (s)he is

attended immediately. Otherwise the user needs to wait in a queue until a server

becomes available. Simple queueing systems are defined by the arrival pattern, the

service mechanism including the number of servers, the distribution of the service

times, the capacity of the waiting room, the size of the customer population and

the discipline, that is the order in which the users in the queue are selected for

service. The problem as stated before can be modelled as a queueing system with

the following characteristics:

• Arrivals to the system: Machines (users) get periodically into the system

and are declared “non-operative” when stopping for being served.

• Service mechanism: If any of the c servers is idle, an incoming user is attended

immediately; otherwise, (s)he needs to wait in the queue until a server gets idle.

• Finite population: The number r of users is finite.

• Discipline: The order of the queue is FIFO, meaning the user “first in the

system” (stopped to be maintained) is “first out” (starts maintenance).

• Steady state: We assume the system to work under stationarity.

If we assume that the operational times To and the maintenance times Tm vary

independently according to exponential distributions with means 1/λ and 1/µ respectively, the problem becomes an M/M/c//r queueing system. When assuming

To or Tm to follow another distribution not being an exponential, e.g. a gamma, the

first (second) of the M’s is replaced by a G.

A steady-state solution of the queueing system always exists as the population

of users is finite and the size of the queue cannot increase to infinity. The steady

state solution of the number of non-operating users in the system, Nno , in case of

the M/M/c//r queuing system depends on the parameters λ and µ and the number

of crews c [GH98]:

On bayesian design in finite source queues

8

n

>

< (r −r!n)!n! µλ p0 ,

n = 0, 1, . . . , c − 1

n

P (Nno = n|λ, µ) =

λ

r!

>

p0 , n = c, c + 1, . . . , r.

:

n−c

µ

(r − n)!c

P (Nno = 0|λ, µ) =

n=0

(1)

c!

where p0 denotes P (Nno = 0|λ, µ), evaluated from:

" c−1

X

1383

r!

(r − n)!n!

n

λ

µ

+

r

X

n=c

r!

(r − n)!cn−c c!

n #−1

λ

µ

The distribution of the time Tq a machine needs to wait for maintenance is also

known in this model, namely [GH98]:

8 c−1

X (r − n) P (Nno = n | λ, µ)

>

>

>

, if t = 0

>

>

>

r − E(Nno | λ, µ)

< n=0

r−1

P (Tq ≤ t | λ, µ) = X

(r − n) P (Nno = n | λ, µ)

>

Fga (t | n − c + 1, cµ)

>

>

>

r − E(Nno | λ, µ)

>

n=c

>

:

+ P (T = 0 | λ, µ)

if t > 0

(2)

q

Rt

and 0 if t < 0, where Fga (t | a, b) = 0 Ga(s | a, b)ds, t > 0 stands for the

distribution function of a Gamma with expectation a/b and variance a/b2 .

2.2 Reliable maintenance

The number Nno of non-operating users in the system and the time Tq that a machine

has to wait for maintenance are classical congestion measures in queueing systems.

A popular summary measure of system performance in machine repair models is the

operational availability:

Ao =

E(To )

,

E(To ) + E(Tno )

where Tno = Tm + Tq is the non-operational time and To is again the operational

time between consecutive maintenances [KGE98], [RKK00]. It can be seen as a first

order approximation of the expected availability E(A), where

A=

To

.

To + Tno

A queuing system can be designed by determining the minimal c meeting some

demand on the expected availability, or by finding the value of c from which on

the increase of the availability levels out. However, these criteria cannot be applied

directly since the distributions of To and Tno depend on the unknown failure and

service rates λ and µ. Additional statistical reasoning is needed therefore, analyzing

some data to get information on λ and µ and include it into the design. We propose

Bayesian modelling for finding feasible values of c, guaranteeing satisfactory availability with high security, and avoiding a compromise in form of assuming values

for λ and µ. A related design problem in terms of the operational capacity, i.e. the

number of machines working at any time point, has been addressed in [MCMFA05].

For this measure it is also reasonable to consider the probability of fulfillment in

addition to the average fulfillment considered here.

1384

M. Eugenia Castellanos et al.

3 Bayesian maintenance design

In a Bayesian formulation of a queueing model with parameter uncertainty, the

background knowledge is subsumed into a prior distribution for the unknown λ

and µ. Updating this prior by combination with the likelihood obtained from the

measured data results in the posterior distribution. A predictive analysis integrates

all information available on λ and µ contained in the posterior.

3.1 Bayesian model specification

A Bayesian model for a queueing system is given by two levels:

1. Data level. The data consists of no life (or failure) times {to1 , . . . , tono } and nm

maintenance (or service) times {tm1 , . . . , tmnm }, regarded as independent realizations of random variables To and Tm with distributions Fo and Fm , respectively. In an M/M/c//r queuing system, Fo and Fm are exponential distributions

characterized by their means 1/λ and 1/µ.

2. Prior level. In the absence of prior information, a non-informative Jeffrey’s prior

is assumed with independency between λ and µ, p(λ, µ) = p(λ) · p(µ) ∝

(1/λ) · (1/µ). Otherwise, the natural choice for the prior is a product of

Gamma distributions Ga(·|ko , so ) and Ga(·|km , sm ), with parameters (ko , so )

and (km , sm ) expressing the information available on λ and µ. Jeffrey’s prior

corresponds to degenerate Gamma distributions.

The posterior distribution of λ and µ, obtained from combining the prior with the

likelihood, in case of an M/M/c//r queuing system is given by:

p(λ, µ|data) = Ga(λ|no , tno ) · Ga(µ|nm , tnm ),

Pno

Pnm

(3)

with tno = i=1 toi and tnm = j=1 tmj . In the general case of a G/G/c//r queuing

system, there is not necessarily an analytic expression of the posterior distribution,

so that MCMC techniques are needed for approximation.

All system performance measures like the availability A inherit a posterior

distribution from (4). This means that we do not just have an estimate of, say,

P (A ≥ a|λ, µ) for each a ∈ [0, 1], but a full posterior probability distribution for

it, p(P (A ≥ a | λ, µ) | data), specifying the full information and uncertainty in

the model. Estimations, as well as the confidence in them, can be expressed via

percentiles, standard deviations, or probabilities of ranges.

The predictive steady state distribution of A is obtained from the expectations

of the parameter-dependent steady state solutions P (A ≥ a|λ, µ) with respect to

(w.r.t.) the posterior (4),

Z

P (A ≥ a|data) =

P (A ≥ a|λ, µ) p(λ, µ|data) d(λ, µ) , for a ∈ [0, 1].

(4)

Although there will not always exist an analytic formula of the posterior distribution,

Bayesian inference can be performed using stochastic simulation. We generate M

values {λi , µi }M

i=1 from the posterior (4), and then generate values from To |λi and

Tno |λi , µi . In view of the definition of Tno , we need to simulate from Tm and from

Tq using (2). With the simulated values {(to,i , tno,i )}M

i=1 we get draws from the

predicted availability, ai = to,i /(to,i + tno,i ), and can approximate the predicted

average availability.

On bayesian design in finite source queues

1385

3.2 Bayesian performance criteria for reliable maintenance

In a similar line as [MCMFA05], we can reformulate the demand on the availability A

from Section 2.2 in terms of the mean of the predictive distribution P (A ≥ a|data),

for a given level of availability a ∈ [0, 1], or the posterior distribution of the mean

E(A|λ, µ), p(E(A|λ, µ)|data), as follows:

1. Achieving a predicted mean availability larger than a:

E(A|data) ≥ a.

(5)

The predicted mean availability can easily be approximated averaging values

from the distribution of A given the data, using the above algorithm.

2. Achieving a sufficiently large posterior probability β ∈ [0, 1] that the mean availability

P post [E(A|λ, µ) ≥ a] ≥ β.

(6)

This posterior probability can be approximated by Monte Carlo as follows:

P [E(A|λ, µ) ≥ a|data] ≈

#{i, E(A|λi , µi ) ≥ a}

,

M

where in this expression we additionally need an estimate of the expectation in

the numerator, which can be obtained P

from a sample {aki }K

k=1 for each λi , µi ,

k

approximating the expectation by ai = K

k=1 ai /K.

To determine suitable choices of c we select one of these goals and evaluate the corresponding measure for different values of c. In the predictive goal (5), we average

over all possible λ and µ weighted by their posterior distribution, while in the posterior goal (6) we require that the values of λ and µ for which we achieve reliable

performance have high probability. Predictive criteria are easily comprehensive as

they are based on expected system performance; they are perfectly suitable e.g. if

we design many queuing systems and average performance guarantees are sufficient.

Posterior criteria imply that the selected goal is achieved in most of the systems

designed.

3.3 An example

[DVV04] consider a radar consisting of r = 64 identical pieces, which are subject

to break-down and need to be maintained for the radar to work. Following their

assumptions we use λ = 0.00008 (failures/h) and µ = 0.006 (repairs/h), but these

values are usually not known exactly. We generate 50 exponential draws for both To

and Tm using these values of λ and µ. The goal is a mean availability of 90%.

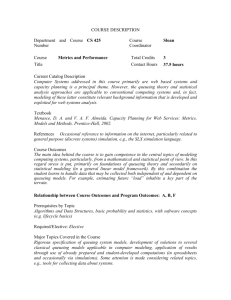

Figure 1 depicts the predicted mean availability, E(A|data), and the posterior

probability of the mean availability being larger than 0.8 or 0.9, P (E(A) ≥ 0.8|data)

and P (E(A) ≥ 0.9|data), for different c = 1, 2, . . . , 10. Monte Carlo integration was performed generating M = 10.000 values {λi , µi }M

i=1 from the posterior

p(λ, µ|data) = Ga(λ|50, 598252.6)· Ga(µ|50, 16062.42).

We see that the predictive goal is satisfied for c ≥ 3, and for c ≥ 4 there is

almost no further increase of the predicted mean availability. The posterior goal is

more demanding than the predictive goal if we insist on a high posterior probability.

1386

M. Eugenia Castellanos et al.

Predicted mean availability

Posterior mean availability

1

1

0.9

0.9

0.8

0.8

0.7

0.7

0.6

0.6

0.5

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.3

0.3

0.2

0.2

Larger than 0.8

Larger than 0.9

0.1

0.1

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

repair crews

8

9

10

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

repair crews

Fig. 1. Predicted mean availability (left) and posterior probability of the mean

availability being greater than 0.8 or 0.9 (right), for several values of c.

We need c ≥ 4 to achieve the posterior goal of an expectation greater than 0.9 with

probability also at least 0.9. When requiring only an expectation greater than 0.8,

c ≥ 3 crews satisfy this goal with probability more than 0.9. A reasonable choice

would thus be c = 4 or c = 3.

We note that the situation in [DVV04] is more complicated. The radar still works

if a few pieces are out of order, and we omit spares. The next section reports further

extensions of the basic model illustrated here.

4 Extensions

All but the simplest modifications of the M/M/c//r queueing system lead to a

severe increase of statistical and computational demands. We briefly outline three

extensions along with possible solutions: the first one maintains the model structure

and the extension only consists in the distribution of the life and the service time. The

second one maintains the same basic queueing model, but the complexity increases

by considering many queuing systems working independently. The third extension

deals with a queueing network with many connected queues. There are many more

8

9

10

On bayesian design in finite source queues

1387

interesting extensions of queuing systems: the distribution of the life times can vary

due to aging, there can be patrolling services, spare machines, ancillary operators,

etc.

4.1 G/G/c//r queuing systems

A natural question is to examine the sensitivity of the results w.r.t. the assumption

of exponential life and service times by studying other, more flexible distributions.

Introducing an additional source of uncertainty, we can consider the Erlang distribution, Er(a, b), a popular and flexible distribution in queues which is a particular

Gamma distribution (the first parameter a is an integer). If this model is assumed

for the operational and maintenance times, To ∼ Er(ao , bo ) and Tm ∼ Er(am , bm ),

not only Formulas (1) and (2) describing the steady-state solution and the distribution of the time in queue are no longer valid, but also we need a prior distribution

for the parameters (ao , bo , am , bm ). The resulting posterior distributions can usually

only be handled by MCMC techniques. Consequently, computing the predictive and

posterior criteria, E(A | data) and P [E(A | λ, µ) ≥ a | data] with more general

models needs more sophisticated techniques and computational efforts.

4.2 Independent but quasi-identical queueing systems

This situation is made up by q independent and quasi-identical M/M/ci //ri queueing systems, i = 1, . . . , q. As a typical example of this situation, we consider a

multinational company with several factories at different sites. The factories work

independently and the machines as well as the repair crews have the same characteristics at all sites. The company wants to set up a new factory and uses information

about the reliability of the machines and the quality of the repair teams in the

existing factories to design the new one. Consequently, we assume that the failure rates λ1 , . . . , λq and the maintenance rates µ1 , . . . , µq at the different sites are

random samples from common populations with distributions indexed by some hyperparameters. Bayesian hierarchical models are particularly well suited for dealing

with this multilevel scenario and MCMC methods are required to deduce the system

performance.

4.3 Queueing networks

We consider a system of machines that may break down because of different failures,

requiring different types of repairs. These different repairs share common steps and

follow a fixed protocol that, depending on the type of failure, sends a broken down

machine to a sequence of specialized services. Consequently, the machine waits in

queue for a first service, and after having been attended it waits in another queue

for the next service, and so on. The complexity of such models is due to the fact

that there is an arrival and a service parameter for each queue (node), and the

probabilistic results for the total system are expressed as multivariate distributions.

Sophisticated MCMC techniques and statistical tools are needed for complex queueing networks.

1388

M. Eugenia Castellanos et al.

References

[AB99]

Armero, C., Bayarri, M.J.: Dealing with uncertainties in queues and networks of queues: A Bayesian approach. In: Ghosh, S. (ed.) Multivariate,

Design and Sampling. Marcel Dekker, New York, pp. 57-608 (1999)

[DVV04] De Smidt-Destombes, K.S., van der Heijden, M.C., van Harten, A.: On the

availability of a k-out-of-N system given limited spares and repair capacity

under a condition based maintenance strategy. Reliability Engineering and

System Safety, 83, pp. 287-300 (2004)

[GH98] Gross, D., Harris, C.M.: Fundamentals of Queueing Theory. Third Edition. Wiley, New York (1998)

[KGE98] Kang, K., Gue, K.R., Eaton, D.R.: Cycle time reduction for naval aviation

depots. In: Medeiros, D.J., Watson, E.F., Carson, J.S., Manivannan, M.S.

(eds) Proceedings of the 1998 Winter Simulation Conference, pp. 907-912

(1998).

[K75]

Kleinrock, L.: Queueing Systems. Volume I: Theory. Wiley, New York

(1975)

[K76]

Kleinrock, L.: Queueing Systems. Volume II: Computer Applications. Wiley, New York (1976)

[LK00]

Law, A.M., Kelton, W.D.: Simulation Modelling and Analysis. Third Edition. McGraw-Hill Education (2000)

[M03]

Medhi, J.: Stochastic Models in Queueing Theory. Second Edition. Academic Press (2003)

[MCMFA05] Morales, J., Castellanos, M.E., Mayoral, M.A., Fried, R., Armero, C.:

Bayesian design in queues: An application to aeronautic maintenance.

Working paper, Universidad Miguel Hernández, Elche, Spain (2005)

[RKK00] Rodrigues, M.B., Karpowicz, M., Kang, K.: A readiness analysis for the

argentine air force and the brazilian navy A-4 fleet via consolidated logistics support. In: Joines, J.A., Barton, R.R., Kang, K., Fishwick, P.A.

(eds) Proceedings of the 1998 Winter Simulation Conference, pp. 10681074 (2000).