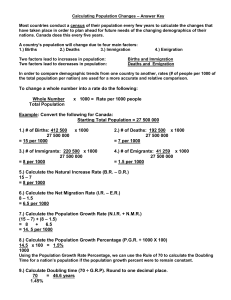

EVERY KID COUNTS in the District of Columbia 1 2

advertisement