Moving Forward: The Future of Consumer Credit and Mortgage Finance

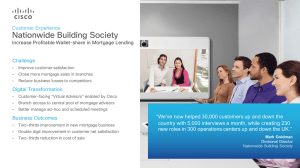

advertisement