Understanding Predatory Lending: Moving Towards a Common Definition and Workable Solutions September 1999

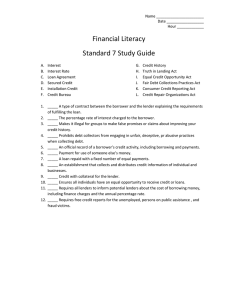

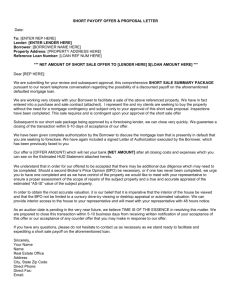

advertisement