Community Development Corporations and Smart Growth: Putting Policy Into Practice October 2000

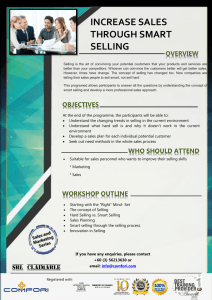

advertisement