Common European Guidelines on the Transition from Institutional to

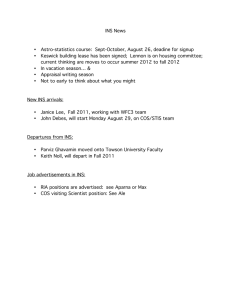

advertisement