Document 14780732

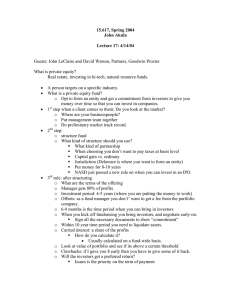

advertisement