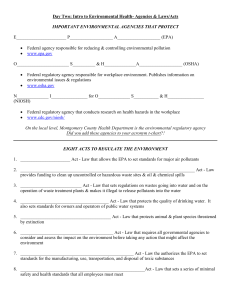

T Implications of EPA’s proposed Boiler MACT rules B G

advertisement

Implications of EPA’s proposed Boiler MACT rules By Gale Lea Rubrecht T he U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has proposed new national emission standards for hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) for industrial, commercial, and institutional boilers and process heaters, known as the Boiler MACT (Maximum Achievable Control Technology), with separate standards applicable to boilers located at either major or area sources. 75 Fed. Reg. 32,006 and 31,896 (June 4, 2010). EPA is obligated to finalize the rules by Dec. 16, 2010. If EPA meets this deadline, then existing sources must achieve the standards by late 2013 or early 2014, and new units must achieve the standards upon the later of startup or publication of the final rules in the Federal Register. Although the standards are not yet final, owners/ operators of boilers and process heaters should evaluate whether their affected units can meet the proposed standards and, if not, their compliance options. Facilities contemplating purchasing a new boiler or process heater should include the standards in their decision-making process. This article highlights some of the features of EPA’s proposals that owners/operators of boilers and process heaters should consider. Because boilers are found throughout industry, commercial establishments, and institutions, the proposals would impact numerous sectors of the economy, including chemical and manufacturing plants, oil and gas extractors, pulp and paper mills, petroleum refineries, steel works, shopping malls, hospitals, and universities. However, the proposed standards generally do not apply to power plants. EPA is developing a separate MACT standard for power plants that EPA is required to propose and finalize in 2011. The major source Boiler MACT would apply to any new or existing boiler or process heater located at a major source, with certain exceptions (e.g., a unit subject to another MACT standard or a unit that combusts “solid waste”). A “major source” facility emits or has the potential to emit, considering controls, 10 tons per year of any individual HAP or 25 tons per year of any combination of HAPs. The minor source Boiler MACT, which includes “Generally Available Control Technology” (GACT) as well as MACT standards, would apply to any new or existing boiler located at a HAPemitting area source (i.e., nonmajor source) with similar exceptions and also an exception for natural-gas-fired boilers. As mentioned above, the proposals would not apply to sources that combust “solid waste.” On the same day that EPA released the proposed Boiler MACT rules under Section 112 of the Clean Air Act (CAA), EPA issued a proposal to define nonhazardous secondary materials that are solid waste. 75 Fed. Reg. 31,844 (June 4, 2010). Whole tires and coal refuse from legacy coal piles are examples of materials EPA is proposing be considered solid waste when burned in a combustion unit. Units combusting solid waste are considered incinerators subject to regulation under Section 129 of the CAA and not boilers. Under a separate, fourth rulemaking, EPA proposed revisions to the rules regulating HAP emissions from commercial and industrial solid waste incineration (CISWI) units incorporating EPA’s proposed definition of solid waste. 75 Fed. Reg. 31,938 (June 4, 2010). Depending upon the final definition of solid waste adopted for combustion units, some units that might otherwise fall under the boiler source category may be classified as CISWI units and subject to those standards instead. Under the MACT, EPA is proposing to establish numerical emission limits, a work practice standard, and a one-time energy assessment to identify any cost-effective energy conservation measures. Based upon unit status (i.e., new or existing), unit design, and fuel type, EPA is proposing eleven subcategories under the major source Boiler MACT and three subcategories under the minor source Boiler MACT rule. For most existing major source boilers and process heaters having a design heat input capacity equal to or greater than 10 million British thermal units per hour (mmBtu/hr), EPA is proposing numerical emission limits for: mercury; dioxin/furan; particulate matter (PM), as a surrogate for nonmercury metals; hydrogen chloride (HCl), as a surrogate for acid gases; and carbon monoxide (CO), as a surrogate for nondioxin and organic HAPs. The area source proposal would establish limits for only mercury, PM, and CO. The limits for new units are more stringent than the limits for existing units, and the limits for both new and existing units are more stringent than the limits in the September 2004 Boiler MACT vacated by the D.C. Circuit in 2007. EPA is not establishing separate emission standards for periods of start-up, shutdown, and malfunction. The same emission limits would apply at all times. Risk-based standards, known as health-based compliance alternatives, that were included in the vacated rule are not an option under the 2010 proposal. Many coal- and biomass-fired units may be unable to meet the new stringent limits. Owners/operators may, therefore, need to consider options such as permit limits on HAPs to avoid being a major source, installing controls, switching fuel type, and even shutting down. Averaging emissions, however, is an alternative compliance approach that EPA supports. Emissions averaging would be limited to PM, HCl, and mercury and could only be used for emissions of the same types of pollutants among existing boilers and process heaters in the same subcategory at a single affected source. Because the emission reductions from averaging must be equivalent to or greater than the reductions from controlling emission points to the numerical limits in the absence of averaging, EPA is proposing to cap the emissions from each of the sources in the averaging group at the emission level being achieved on the effective date of the final rule. Additionally, EPA is also proposing to apply a 10 percent discount factor to emission averaging, which limits averaged emissions to 90 percent of the numerical emission limits. For all units that burn gas and for small, existing boilers and process heaters that burn a fuel other than gas, EPA is proposing a work practice standard that would require implementation of a tune-up program. Tune-ups would be required annually for natural-gas- and refinery gas-fired units equal to or greater than 10 mmBtu/hr and biennially for all other affected units. The tune-up would involve inspecting the burner, flame pattern, and system controlling Published in Trends Volume 41 Number 6, July/August 2010. © 2010 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association. the air-to-fuel ratio; minimizing emissions of CO per the manufacturer’s specifications; and measuring the concentration in the effluent stream of CO before and after making any adjustments. Minimizing and measuring CO emissions are important because the presence of CO indicates incomplete combustion and elevated organic HAPs. Beyond emission limits and work practice standards, EPA is proposing to require that all existing sources having affected units perform a one-time energy assessment to identify any cost-effective energy conservation measures, which would be defined as any measure that has a payback of energy saving investments within two years or less without regard to the impact on HAP reductions. According to EPA, facilities can reduce fuel/energy use by 10 to 15 percent by using best practices to increase their energy efficiency. Depending upon the size of the facility, EPA estimates the cost of an energy assessment to range from $2,500 to $55,000. The energy assessment must be performed by someone who has successfully completed the Department of Energy’s Qualified Specialist Program for all systems or a professional engineer certified as a Certified Energy Manager by the Association of Energy Engineers, using EPA’s ENERGY STAR Facility Energy Management Assessment Matrix. This tool identifies gaps in current energy management practices and provides steps to close the gaps. It may also raise issues concerning confidential business information for owners/operators of process heaters. The energy assessment includes a visual inspection of the boiler system; the determination of operating characteristics of the facility, energy system specifications, operating and maintenance procedures, and unusual operating constraints; identification of major energy-consuming systems; a review of available architectural and engineering plans, facility operation and maintenance procedures and logs, and fuel usage; a list of major energy conservation measures; the energy savings potential of the energy conservation measures identified; and a facility energy management program. The program must be developed according to ENERGY STAR guidelines. Following the energy assessment, a report identifying the cost-effective energy conservation measures must be submitted to the appropriate authority and detail the ways to improve energy efficiency, the costs and benefits of specific improvements, and the time frame for recouping those investments. Large facilities may select in-house engineers to undertake training to become a certified energy management specialist. Small facilities may choose instead to rely upon outside consultants. Because the current number of certified energy management specialists is limited, outside consultants as well as in-house engineers may want to become qualified in order to meet the expected demand. For units subject to emission limits, compliance would be demonstrated by an initial performance test followed by annual performance tests consisting of stack tests, fuel analyses, or a combination of both. Stack tests must be conducted at maximum normal operating load, with a minimum of three separate test runs for each performance test. Continuous monitoring of parameters based upon the size of the boiler or process heater, fuel type, and pollution control device would be required. EPA is proposing, for example, that continuous emission monitoring systems (CEMS) for CO and oxygen be installed and operated on units with heat input capacities of 100 mmBtu/hr or greater as well as PM CEMS for units with capacities of 250 mmBtu/hr or greater. The proposed rules also include notification, recordkeeping, and reporting requirements. Initial notifications would likely be due in April 2013 for existing sources and fifteen days after startup for new sources. Records of each required boiler tune-up and records demonstrating compliance with limits and monitoring requirements would be required. If nonhazardous secondary materials are burned, records would be required to demonstrate that the materials were not solid waste. Data from each performance test would be reported electronically by entering emissions date into EPA’s WebFIRE database. The database may prove to be an easily accessible, current resource of emissions data on which to base emissions factors traditionally used in developing emissions inventories and control strategies. It should also reduce the burden of future data collection efforts. EPA’s proposals, if finalized, will undoubtedly impose significant burdens and costs upon owners/operators of affected units. While sources typically conduct tune-ups, EPA’s proposed energy assessment represents a new approach to reducing HAPs. The proposals would require only identification of energy efficiency measures. Whether EPA’s next step will be to require implementation of those measures is the question. Gale Lea Rubrecht is a member of Jackson Kelly PLLC and can be reached at galelea@jacksonkelly.com. Published in Trends Volume 41 Number 6, July/August 2010. © 2010 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.