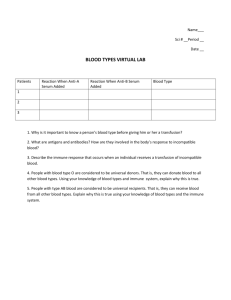

I ICH

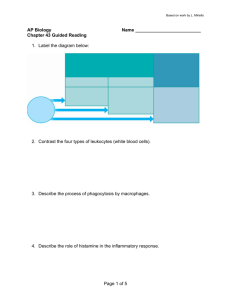

advertisement