2013 A TOBACCO-FREE FUTURE AN ALL-ISLAND REPORT ON TOBACCO,

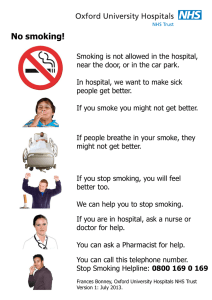

advertisement