Substance Use in New Communities: A Way Forward

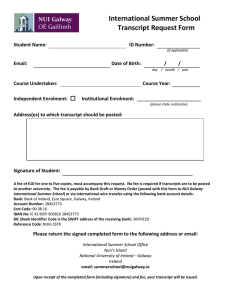

advertisement