Document 14751550

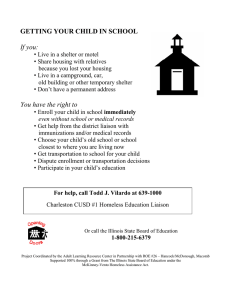

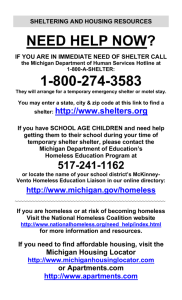

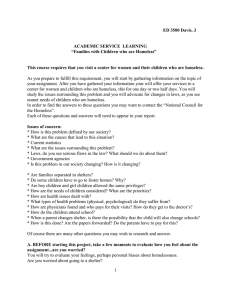

advertisement