The Transfer of Child Care Worker Education The T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood

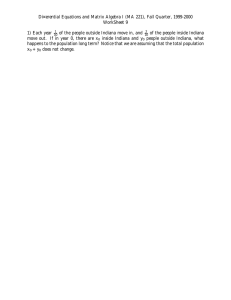

advertisement