DIE WELT DER SLAVEN Sonderdruck XXXI. 2

advertisement

Sonderdruck

DIE WELT DER SLAVEN

HALBJAHRESSCHRIFf FOR SLAVJSTIK

Jahrgang

XXXI. 2

N.F.X,2

1986

VERLAG OTTO SAGNER

MDNCHEN

DIE WELT DER SLAVEN

HALBJAHRESSCHRIFT FUR SLAVISTIK

BegrUndet von Erwin Koschmieder

UnteT der Schriftleitung von

Heinrich Kunstmann

herausgegeben von

Henrik Birnbaum' Dietrich Gerhardt· Wolfgang Gesemann

Reinhold Olesch . Peter Rehder . Helmut Schaller

Josef Schrenk' Joseph Schiltz, Erwin Wedel

Redaktion

Peter Rehder

Jahrgang XXXI, Heft 2

N.F.X,2

Inhalt

I. Artike1

u

R. R 1:i i:: k a: lYpologie del" Diathese slavischer Sprachen in parametrischen

225

Variationen

...............................

H. Birn baum: Roman Jakobsons Untersuchungen zum kulturellen Erbe des

slavischen Mittelallers . . . .

.................

H. Kunstmann: Woher die Huzulen ihren Namen haben

G. Toops: Vocative Forms and Vowel Reduction in Bulgarian...

275

317

324

E. Hansack: Das Kyrilliseh-mazedonisehe Blatt und der Prolog zum Bogoslo. ............. , . .

336

vie des Exarehen Johannes. .

A. A. Alekseev: Der Stellenwert der Textologie bei der Erforschung altkir. ......... , .

415

ehenslavischer Obersetzungstexte .

J. Danhelka: In memoriam Miloslav Svab.

439

I I. Rezension

Ch. Hanniek: P. Kawerau, Ostkirehengesehichte IV. Das Christentum in

Siidost- und Osteuropa. Leuven 1984 ..

443

Einsendung vo.n satifertigen Artikeln (bitte unbedingt unsere Typoskriptregeln anfordern) bzw. von Rezensionsexemplaren an den Schriftleiter Professor Dr. Heinrich

Kunstmann, lnstitut filr Siavische Phil%gie der Universittlt Milnchen, GeschwisterScholl-Platz 1, D-8000 Milnchen 22. - Eine Verpflichtung zur Besprechung oder

Rucksendung zugesandter BUcher kann nicht iibernommen werden. Rezensionen

nur naeh Riicksprache mit dem Sehriftleiter.

ISSN 0043-2520

© 1986 by Verlag Otto Sagner, MUnehen

Aile Rechte vorbehalten

Gesamtherstellung: GebT. Pareus KG

Printed in Gennany

Gedruckt mit Unters!Ulzung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft

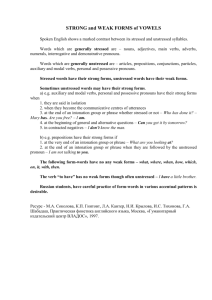

VOCATIVE FORMS AND VOWEL RED UCT I ON

IN BULGARIAN

Grammarians generall y agree that Bul garian vocative noun form s arc

regularly characterized by o nl y three desinences - -1.1, -e and -0 - and

that these form s a re ex hi bited o nl y by masculine and femi nine nouns

whose uninnected (si ngular) forms have the desinence -0 as well as

masculine nouns w ith -0 desinence (Aronson 1968, 60; Scatton 1984,

140). However conventiona l t his classificatio n of vocative forms may be,

it can be cons idered al least partly accurate only insofar as "form" is

understood to be orthographically distinct. If, on the other hand, forms

arc correctly identified on the basis of p honemic oppositions, then the

capacity for vocative fo rmation can in no way be limited to those

mascu line and feminine nou ns ment ioned above. I propose that, in addition to such nouns, a ll o ther stem-stressed singular nouns with desinential -a, -e and -0, in a ll but the "highest style" of spoken Contemporary

Standard Bulgarian (CSB), simila rly exh ibit a grammatical opposit ion

vocat ive: non-vocative, forma lly characterized by the phonemic oppositions l a/:/;J! ,1e/:/il a nd lolju/. While this proposition is hardl y

origi na l, it has been rejected (Pdov 1980,238-9). Its relevance to the

establishment of an inventory of unstressed vocalic phonemes, ultimately

vali d for all spoken styles of CSB, has likewise been overlooked.

Grammars and linguistic studies of CSB typicall y make relat ively brief

mention of vocative forms. For example, t he second volume of the

Bulgarian Academy Grammar (1983), consisting of 511 pages, devotes the

equivalent of only two pages to a discussion of them. Thi s is understandable inasmuch as a descriptio n of vocative form s, at least from an orthographic point of view, is essentially com plete once the distribution of

the three vocative dcsinences is defined. To summarize E. A. Scatton

(1975, 163), whose a na lysis parallels that o f H. I. Aronson (1968, 60 - 1),

the vocative dcs inences -u, -e and -0 occur in the following morphophonemic environments:

Vocative forms and vowel reduclion in Bulgarian

(I) Desinence Environment

-u

In masc. nouns with

stems

in high, non·back,

anterior consonantal or

in / jl

-e

In masc. nouns with

stems

in non·high, non·back,

anterior consonantal,

except for stems ending in

Icl or the suffix I-i n-I

In fern. nouns with stems

in l·c·1 and sometimes

I- k-I

-0

Elsewhere

325

Examples

drugar 'comrade':

drugdrju

ratdj 'farmhand': rattiju

slavej 'nightingale':

slaveju

utftel 'teacher': utftelju

brat 'brother': brdte

minfstar 'minister':

minfstre

narod 'nation': narode

tedtar 'theatre': tedtre

carica 'czarina': carfee

gospOtiea 'Miss': gospOtice

Ivdnka (given name):

Ivanke

ulitelka 'teacher': utftelke

bdlgarin 'Bulgarian':

bdlgarino

gospot.d 'Mrs!: gosp6to

kradic 'thief': kradeeo

majka 'mother': mdjko

mat 'man': mato

pa/dt 'executioner': palato

pala~ 'poodle': pald~o

seslrd 'sister': sestro

siromdch 'poor man':

siromacho

stopanin 'landlord':

stopdnino

utenfk 'pupil': utenfko

tend 'woman': Uno

Irregular vocative forms, including those that occur in addition to the

regular ones, must be listed:

326

Gary lOOps

(2) Irregular

Bog 'Ood': Bote

tovik .'man': lovete

dllJlerjo 'daughter': d41te

gospod 'Lord': gospodi

gospodln 'Mister'; gosp odfne

orei 'eagle' : 6rl'0

Olec 'father (priest)': 61&

petel 'rooster'; pitro

stdrec 'old man'; suirle

sllpnig 'husband': sdpru!.e

zel 'son/ brother·in·law'; zitko

.

Regular -- Irregular

brat 'brother': brdte -- bnitko

{orbodl/ja 'rich man': lorhad!fjo -- lorbadtf

drugdr 'comrade': drugdr)u

-- drugdr'o

jundk 'hero': junako -- juntUe

kon 'horse': kon)u -- kon 'o

sfn 'son': s(ne"" sInko

/voTic 'creator' (\loreca -- (}Jorte

vojn(k 'soldier'; vojn/ko

-- vojn({e

While the foregoing description of vocative forms is recommended by

its economy and thoroughness. there remain, in my view, three basic prob

lems, the first of which is more or less evident from the material presented

in the Bulgarian Academy Grammar (1983, 114- 5; see also Cernov 1979,

33 - 4). First, conventional descriptions like the one above fail to take into

account the special status of personal names. An application of the given

rules yields, therefore. the following infelicitous form s: (a) vocative forms

of surnames, which do not exist; (b) vocative form s of masculine given

names ending in -a or -j - the forms · Blagoju « Blago)), ·Dragoju

« Drago)), ·Nikoldju «Nikold)), ·Nikdlo « Nik6la), ·flijo « IUja)1

do not exist; and (c) vocative form s of feminine given names terminating

in -a which native speakers describe as peasant-like or extremely familiar

and which the Bulgarian Academy Grammar (1983, 143) describes as having a " nuance of stylistic inferiority [stilisJilna nep4lnocennos/] and crudity {grubovatost1" - Marijo « Marija), EMno « Elena), Margar(to

« MargarttaF. Common nouns with stem-final / -k-/ exhibit the opposite

I Cernov (1979, 33) cites vocati ve (arms for DObri; DObre, Dragoj: Drag~, Vikentij ; Vikentip. The Bulgarian Academy Grammar (1983, 11 5) states that the first two fo rms

do not exist.

I Hubenova et al. (1983a, 125) use the vocative Lilidno in the address of a contemporary leiter, where o ne would expect Lilidna. The few other feminine vocative forms in - 0,

Ka({no« Ka((na) and Cveto « Cveta) , a ppear in archaic contexts (Hubcnova 1983b, 200;

236).

Vocative forms and vowel reduction in Bulgarian

327

tendency. While the personal names (vocative forms) Zfvke « Zfvka),

lvdnke « Ivdnka) are stylistically neutral, the corresponding vocative

forms of common nouns, e. g. drugdrke 'comrade (fern.), « drugdrka),

prepodavdtelke 'teacher' « prepodavdtelka), are considered crude and

are replaced by drugdrko and prepodavdtelko, resp.

The se<::ond problem is that the description of vocative forms given

above applies for the most part only to nouns occurring in isolation, i. e.

address clausesJ consisting of a single noun. Thus, conventional descriptions of vocative forms do not account for the fact that the vocative gospodfne 'Mister' is not used in the address clauses gospodfn Pop6v 'Mister

Popov' or gospodfn d6ktore '(Mister) Doctor,' while the vocative

gosp6fice 'Miss' is consistently used in address clauses (gosp61.ice

Pop6va 'Miss Popova'); or that both the non-vocative gospol.d and the

vocative gosp6t.o occur not only in multiple-noun address clauses (gospol.d "'" gosp6t.a Popova 'Mrs. Popova') but also in isolation (cf. Hubenova 1983a, 107: D6biJr den, gospot.d 'Good day, ma'am'). Similarly, in the

address clause Drugdrju akademfk Aleksdndiir Pop6v (as opposed to the

theoretically imaginable ·Drugdrju akademfko Aleksdndre Pop6v)

'Comrade Academician AleksandlIr Popov', the appellative function of

only the first noun is formally marked (this usage is attested also in Old

Church Slavic, Greek and Latin, cf. Vaillant 1977,24)". While it is clear

from the data that vocative forms are (for the most part, see Note 4) semantically marked "appellative" and the non-vocative are not so marked,

the question of which contexts favor or require the unmarked form in

address clauses is best reserved as the topic of a separate study.

To the extent that morphophonemic analyses of CSB are not applied

solely to the "orthoepic norm [provogovorna norma]" (which proscribes

the reduction of unstressed vowels), the third problem, which I have

primarily undertaken to discuss here. arises from the fact that the vocative

desinences are inherently unstressed (this entails stress retraction for

I I follow Brooks (1973) in the use of the term "address clause!'

• I use the term "vocative" in reference to form, "appellative" in reference to function. Non-vocative forms are not strictly non-appellative, nor, according to Mladenov

(1929. 225), are vocative forms strictly appellative, cr. v{ka( go Stojdne 'they call him Stojan,' Jovdne me kdzva( 'my name is Jovan~

328

Oary lOOps

nouns with desinential stress - .tend 'woman': Uno). According to Scat·

ton (1975, viii), "in all but the most formal styles of CSB unstressed non·

high vowels are raised towards their higher counterparts: Ie) ..... [il. (a) .....

'<II , [0] ..... [u} ." This statement suggests that vowel raising, or vowel reduction, which ScattoD describes as a "low-level phonetic phenomenon"

(1975. viii), operates in all unstressed syllables, including the unstressed

vocative desinences. From the published literature dealing at least in part

with the question of vocative forms. it is clear, however, that this is not

the case: on the contrary. the unstressed desinential vowels of vocative

forms are never raise<P.

In this regard, S. Mladenov (1929, 86) states: "The modern Bulgarian

literary language faithfully maintains etymological 0 even in unstressed

syllables, whereas in the diaJects, both eastern and western, the pronunciation is rather that of a reduced Q, which aJmost or completely sounds

like ordinary u ... Even in dialects with the most extensive reduction, 0

in the vocative remains pure 0. albeit unstressed."

Thus, a Bulgarian speaker who pronounces goni 'forest' as [gura] will

not pronounce the vocative goro as *(g6ru], but as [g6ro]'.

P. Pa~ov (1980, 238) makes the same observation with respect not only

to 0. but also to e: "In Contemporary Standard Bulgarian it is mandatory

that an unstressed vowel not be reduced only [when it functions] as a vocative form ending . .. In these instances there is no reduction even in the

dialects, including the central Balkan dialect. in which a clear distinction

is made between "Stojfu, 'l.ndj" [sic, 'Stojl!o knows'] and "Kil!': Stojfo"

['Say, Stojoo'], "Dil ignijm nil konfi" ['Let's play (hobby) horse'] and

"Dfj, df. konfe" ['Go, go, horse'].

Elsewhere, V. A. Cernov (1979, 33) cites Dobre as the vocative of Ddbrio a masculine given name which, according to the Bulgarian Academy

j Scanon (1984, 19; 55; 72) elaborates that there are three hierarchicaily ordered

systems of vowel reduction, yielding varying inventories of 5, 4 and 3 unstressed vocalic

phonemes. resp. Given the oppositions laJ :/~ / , 101 :/ul and lei :/;/, Bulgarian speakers

may. in unstressed syllables. neutra1iu the first opposition, the first two or all three o ppositions (in that order). Scanon's observations, however, still ignore the fact that even in a

system of maximal vowel reduction (entailing the neutralization of all three oppositions),

the unstressed vocalic desinences of vocative forms are not subject to reduction.

, Although I am concerned here with CSB, it is obvious that the extent to which the

pronunciation of a speaker of CSB deviates from the orthoepic norm is dialectaJly influenced.

Vocative rorms and vowel reduction in Bulgarian

329

Grammar (1983, 115), has no vocative form: apparently some Bulgarian

speakers misinterpret the final·; ([i]) as a "reduced" allophone of fe/,

which they pronounce as [E] when addressing someone with that name.

The appellative function of the unstressed but unreduced vocalism is

also reflected occasionally in written works; cf. the following stanzas

from Christo Botev's poem ChadU DimftOr (Cernov 1979, 83). Words

ending in unstressed ·e regularly rhyme with those in unstressed ·i, except

the appellative sl6nce 'sun: which rhymes with end-stressed sOrce 'heart'7:

(3) tdtva e segd . .. Pejle, robin;,

lez tdIni pesni! Grej i ii, sl6nce,

v laz r6bska zemjd! Ste da zagine

i 16ja jundk ... No ml6km; sOrce.

...

Denem mu sjdnka pdzi ortica

; v41k mu krotko rdnata blite;

nad nego sok61, juna~ka ptlca.

; tja se za brat, za jundk grili.

One should also note that while the Bulgarian Academy Grammar

(1983 , 115) states that masculine nouns (both proper and common) whose

uninflected form s end in · 0 do not have corresponding vocative form s,

it paradoxically notes elsewhere (1982, 54) that "the vowel [0] undergoes

a relatively weaker degree of reduction or undergoes almost no reduction

[at all] when it fulfills the function of a sufflx for the vocative form of

nouns." Without providing phonetic transcriptions, the Academy Grammar (1982, 54) cites as examples the sentences Milko, ela 'Mitko, come'

and Pfsach na Mflko 'I wrote to Mitko' (apparently the contexts alone are

sufficient for a native Bulgarian speaker to distinguish between the two

phonetic realizations to which the Grammar alludes). Using the Gram-

1 PaJov (1980, 242) aTlues that poems do not reliably indicate whether two words

with different endings actually rhyme or not. In citing the following stanza rrom N. Furnadfiev, however, Palov actually suppons the proposition that unstressed ~ in the vocati ve

pdpe «pop 'priest') cannot conceivably be reduced to rhyme with sn6pi 'sheaves';

Omrdznacha m; tv6jte PUsti dumi, I omrhznaf si mi mn6go. djddo pdpe! I V glm ifte pdri

kar6 smllrt kurfJima / j gnijar po charmdna m6jte sn6pi.

330

Gary Toops

mac's transcriptions of post-tonic 0, however, one may establish a fairly

clear distinction between the phonetic realizations of Milko in its appellative function and the graphically identical noun in its nonappellative function:

(4) Appellative:

Non-appellative:

[mitkoJ -- [mitk9]

[mitk9J ,.., [mitkQ] ..... [mitku]

In seeking to determine whether such varying degrees of vowel height

constitute a phonemic opposition (i. e., vocative I mitkol vs. non-vocative

I mftku/ ), a user of the Bulgarian Academy Grammar is hard put to find

an unequivocal answer. For example, the Grammar (1982, 59) clearly regards vocative: non vocative as a grammatical opposition, going so far

as to speak of a vocative case (pade~. It establishes (1982, 60) two unstressed allophones of 101 - (9] and (Q] -, which differ from each other

in degree of closure (height). Yet the Grammar (1982, 54-5) maintains

that the phonetic realization of the grammatical opposition voca·

tive: non·vocative is purely allophonic. In other words, the Grammar

would have the user believe that, given two or more positional variants,

one is realized when the noun functions appellatively, another when the

noun functions non·appellatively. This is clearly a contradiction in terms

(phonetic distinctions that signal grammatical oppositions being phone·

mic, not allophonic).

It is apparent that the Grammar seeks to avoid any "deviation from

the orthoepic norm influenced by the eastern Bulgarian unstressed vocal·

ism" (1982, 58). With regard to the allophone (Ql, which. according to

the Grammar, occurs primarily in post·tonic position, but may occur in

any unstressed syllable other than the immediate pretonic, the Grammar

(1982, 55) states: "In terms of auditory impression (po sluchovo vpe·

i!atlenie] it is identified as a sound close to the vowel (u], with which,

however, it does not coalesce." Of unstressed l ui ([u)) the Grammar

(1982,57) states: "In certain positions ... it tends toward a broader arti·

culation. which approaches that of unstressed [Q] in second pretonic or

post·tonic position." Under no circumstances. then. do unstressed 0 and

u lose their distinctive "o·like" and "u·likc" quality, resp. In view of the

sonagraph frequencies which the Academy Grammar (1982, 53 - 6) cites,

however. this seems unlikely. By listing the allophones of 101 and l ui in

increasing order of frequency, we see that while stressed l ui and 101 are

maximally opposed with respect to the feature highl low (F .), unstressed

331

Vocative forms and vowel reduction in Bulgarian

lui falls clearly within the frequency range of unstressed 10/. In terms of

the feature back·round (Pz). the frequency ranges of unstressed l ui and

101 likewise overlap:

F,

(5)

stressed lui:

post·tonic 10/:

unstressed lui:

pretonic 10/:

stressed 10/:

[ul

[01

[iI]

[9]

[6]

(h;gh)

300 hz

305- 325

380

4115

478

(low)

F,

(back·rounded)

posHonic 10/:

stressed lui:

pretonic 10/:

stressed 10/:

unstressed l ui :

[01 755 - 775 hz

[ul 850

[91 855

[6] 894

[ill 900

(front)

In order to determine, then. whether the functional opposition appella·

tive: non·appellative of two graphically identical nouns with word·final

·0, -e or -0 can be formally marked by the phonemic oppositions

la/: 1:)1. lei : Iii or 101: l ui, it is perhaps better to consider the two "stylistic extremes" of spoken CSB together with their respective inventories

of unstressed vocalic phonemes. To the extent that a speaker adheres to

the strictest prescriptions of the orthoepic norm (the "highest" spoken

style), it is essentially moot to ask whether there exist vocative forms that

are orthographically indistinguishable from non-vocative forms. Accord·

ing to Aronson (1968, 31), the orthoepic norm prescribes an artificial

spelling pronunciation. In its strictest application. unstressed vowels dif·

fer from stressed vowels only quantitatively. length being a concomitant

of stress 8• In this style of spoken Bulgarian, six vocalic phonemes occur

both in stressed and in unstressed syllables:

I According to the Bulgarian Academy Grammar (1982, 47), the difference in length

between unstressed and stressed a in the word glavd 'head' is 0.05 second (stressed: 0.12

second; unstressed: 0.07 second). - It has been suggested (Piclov 1980,239) that unstressed word-final -a, -f! and -0 do not undergo reduction because they are pronounced long

when the noun functions appellatively. If so, we would have to conclude that Bulgarian has

phonemic length. The inventory of stressed vocalic phonemes for the orthoepic norm

would accordingly have to be marked for length, and the inventory of unstressed vocalic

phonemes would then be increased to nine (lal , l a, l ei, I U, 10/, 1r,I , 141 , I ii , l uI). PaWv

(1980, 239), however, rejects the notion that lengthening of the vocative desinences is

responsible for the lack of vowel reduction, pointing out that in certain contexts the reo

duced vocalism may also be lengthened (for example, when a name is uttered emphatically

or in an outburst of joy, or repeated by a speaker in response to his interlocutor's failure

10 hear or understand the name the first time it was uttered).

332

Gary lOOps

(6)

Unstressed

Stressed

l ui

I iI

l ui

I ii

10 1

101

lei

lei

101

101

lal

l al

Even if we admit that the unstressed vocalisms differ qualitatively to

some extent from those in stressed position, the unstressed vocalisms are

merely positiona1 variants of the stressed. The inventory of vocalic phonemes in unstressed position remains the same. cr. Aronson 1968, 33:

(7)

Unstressed - "Full Style" Unstressed - "Colloquia/-Literary"

[i)

[u)

[u)

[i)

[;)

[e)

[0)

[e)

[0)

[a" )

[0" )

[A)

Hence, this style admits no phonemic (or even phonetic) distinction between appellative a nd non-appellative Milko, both being realized either

as (mitb") or as [mitko"J.

The opposite "stylistic extreme" admits only three vocalic phonemes in

unstressed position. D. Tilkov (1983. 77) states that in unstressed syllables

in the dialects of eastern Bulgaria, "the open vowels [aJ. [0). [e) are

lacking at the expense of the vowels [~J. [i) and [uJ. In the western dialects

there exists. rather, a more or less noticeable convergence [pribli1.avaneJ

of the open vowels with the corresponding closed ones. For the Bulgarian

speaker it is essentially insignificant whether the speaker pronounces in

an unstressed syllable. regardless of its position in the word. [~J in place

of [a], [u] in place of [0] or vice versa. In other words, as concerns the

absence of stress [neudarenostlal. the oppositions between degrees of

openness are neutralized." Tilkov (1983, 78) establishes the following

phonemic inventories for stressed and unstressed syllables:

Stressed

(8)

Unstressed

l ui

Ii!

I~ I

lei

hi

101

lal

l ui

I iI

Vocative forms and vowel reduction in Bulgarian

333

Tilkov, however, is apparently not concerned, at least in this particular

instance, with the unstressed word-final vowels of appellative nouns' . Pa~ov (1980, 238 - 9), on the other hand, is concerned with them, stating

that in addition to unstressed word-final -e and - 0, unstressed -a is likewise not subject to reduction in those instances when the noun functions

appellatively. Pa~ov cites as examples the personal names GaUna (from

which the vocative GaUno may be formed) and Nik61a (from which a vocative ·Nik610 is not formed): "In address [clauses] not only will the vocative ending -0 not reduce ("Gal(no, zdravej!" ('Galina. hello!'D, but

neither will the ending -a ("Gaf(na. zdravejr' ('Galina. hello!']), and in

this way we distinguish phonetically [izgovornoj "GaUna dojde" ['Galina

came'] from "GaUna. dojde" ['Galina, hel shel it came'] (. . . the comma

after the address in this case does not indicate a pause). The same is true

of the masculine name Nik6la: 'Tova e Nik6la. Nik6la. zapoznaj se s. ..

['This is Nikola. Nikola, meet ... 'j ."

It is clear from these observations that the phonemes l al, lei and 101

must be included in the inventory of unstressed vowels illustrated in (8)

above. By doing so, we achieve the following result:

(9)

Unstressed

l ui

I ii

h i

lei

101

lal

This inventory of unstressed phonemes is the same as that cited in (6).

In my opinion, this is the only one which adequately accounts for the

fact s of both the orthoepic norm and those styles of spoken CSB in

which one or more phonemic oppositions are neutralized in all but the

desinences of nouns marked "appelative"lo. In spoken styles characterized by maximal vowel reduction, then, the phonemic oppositions

l a/ : I;, I, lei : I ii and 101 : l ui formally mark the grammatical opposition vocative : non-vocative, cr.:

, Tilkov uilimately takes vocative form s into consideration in his capacity as author

of pp. 17 - IS8 of volume I of the Bulgarian Academy Grammar (1982).

10 In other wo rds. the re cannot exist an inventory of fewer than six unstressed vocalic

phonemes, since any invento ry that does not include the phonemes /a/, / el and /or 101

automatically fails to account for the occurrence of one or mo re of these phonemes as

unstressed vocative desinences.

334

Gary Toops

(10)

Nikdlo

Safo

ku~e

'dog'

Vocative

I nik61a/

/saf,o/

Non-vocative

I ku~e/

/ ku~i /

i nik61:J/

/ saf,u/

Literalure Cited

Aronson, H. I., 1968: Bulgarian Innectional Morphophonology. The Hague/

Paris. (Slavistic Printings and Reprinlings. 70.)

Brooks, M . Z .• 1977: The Polish Vocative Case - Will It Survive? In: Folia

Siavica 1:2. 165 -7 1.

Bulgarian Academy Grammar 1982 :z BAlgarska Akademija na Naukite. Institut

za bAlgarski ezik 1982: Gramalika na sAvremennija bAlgarski knifoven el.ik I.

Fonelika. Sofia.

Bulgarian Academy Grammar 1983 "" BAlgarska Akademija na Naukite. Institut

za bAlgarski ezik 1983: Gramatika na sAvremennija bAlgarski knitoven ezi k 2.

Morfoiogija. Sofia.

Cernoy, V. A. t 1979: Sravnitel'naja charakteristika dvuch lipologi ~esk i razlit!nych

rodstvennych jazykov (bolgarskogo i russkogo). Sverdlovsk.

Hubenova, M. - A. Dfumadanova - M. Marinova , 1983 a: A Course in

Modern Bulgarian. Part I. Columbus (Ohio). (Corrected reprint of Hubenova,

M. et al., 1964: B~lgarski ezik. P~rva t!ast. Sofia.)

Hubenova, M. - A. Dfumadanova, 1983 b: A Course in Modern Bu lgarian.

Part 2. Columbus (Ohio). (Corrected reprint of Hubenova, M. e/ al., 1968:

Balgars ki ezi k. Vtora (!ast. Sofia.)

Mladenov, 5., 1929: Geschichte der bulgarischen Sprache. Berlin/ Leipzig.

(GrundriB der slavischen Philologie und Kuiturgesch ichle.)

~aovr, P., 1980: Redukcija na giasnite v sa.vremennija knifoven Mlgarski erik.

In: P4rvev, C h. - V. Radeva (comps.): Pomogalo po b~ l garska fonetika. Sofia, 230 - 48.

Scallon, E. A., 1975: Bulgarian Phonology. Cambridge (Mass.).

Scatton, E. A., 1984: A Reference Grammar of Modern Bulgarian. Columbus

(Ohio).

Tilkov, D., 1983: Neopredelenata fonema. In: Bojadfiev, T. - M. S. Mladenov

(comps.): Izsledvanija vArchu bAlgarskija ezik. Sofia, 74 - 8. (lhmslated reprint of Tilkov, D., 1970: Le phoneme indetermine. In: Phonetica 26, 210 -5.)

Vaillant, A., 1977: Grammaire comparee des langues slaves 5. La Syntaxe. Paris.

Vocative forms and vowel reduction in Bulgarian

335

Additional Liter a tu re

Bojadtiev, T., 1980; Udarenieto i zvukovata struktura na bAlgarskata duma. In:

PArvev, Ch. - V. Radeva (comps.): Pomogalo pO bAlgarska fonet ika. Sofia,

230 - 48.

Ivanlev, S., 1955: Edna neopisana upotreba na llenuvata forma (klim vliprosa za

formata na obrMtenieto v blUgarski ezik). In: Blilgarska Akademija na Nauk ite. Otdelenie za ezikoznanie, etnografija i literatura: Sbornik v lest na akademik AleksandAr Teodorov- Balan po slulaj devetdeset i petata mu godi~nina .

Sofia, 271-8.

Ivanlev, S., 1977: Formite za obrMtenie pri sMtestvitelnoto ime "brat". In: BAl·

garski ezik 27:2,142 -3.

Iva nlev, S., 1980: Rimite na Ivan Vazov i Penlo Siavejkov i redu kcijata na glasnite v bAlgarski ezik. In: PArvev, Ch. - V. Radeva (comps.): Po mogalo po bAlgarska fonetika . So fi a, 249 - 61.

Jana kiev, M., 1980: Udarnost (akcentuvanosl) i bezudarnost (neakcentuvanost).

In: PArvev, Ch. - V. Radeva (comps.): Pomogalo po bAlgarska fonetika.

Sofia , 187-94.

Pa$ov, P., 1980: Pravopisni i pravogovorni obsobenosti svArzani s redukcijata na

neudarenite glasni. In: PArvev, Ch. - V. Radeva (co mps.); Pomogalo po bAlgarska fo netika. Sofia, 262 - 8.

Til kov, D. , 1983: Morfoiogiln i pdl ini za ogranilavane na foneti lnOlo dejstvie v

balgarski erik. In: Bojadtiev, T. - M. S. Mladenov (comps.): Izsledvanija vArchu bAlgarskija ezik. So fia , 244 - 52. (Reprint of Tilkov, D., 1981: Idem. In :

Blilgarski ezik 31 : 5, 413 - 9.)

Bou lder, Colorado

Gary To ops

NEUE R SC H E I NUNGEN

AUS DEM VERLAG arm SAGNER, MUNCHEN

SAGNE R S SLAV I STISCHE SAMMLUNG

HERAUSGEGEBEN VON PETER REHDER

Band 8 Litlerae Siavicae Medii Aevi Francisco Venceslao Mare~ Oblatae.. Herausgegeben

von Johannes Reinhart. 1985. Ln. 427 S.

Band 9 Orbini. Mauro: II Regno degJi Slav!. Nachdruck besorgt von Sima Cirkovic und

Peter Rehder. Mit anem Vorwort von Sima Cirkovic. 1985. Ln. 544 S. Faksimile-Edition.

Band 10, I + II Eng e I, Ulrich, Pavica M r a zo vie (Hgb.): Kontrastive Grammatik

Deutsch - Serbokroatisch. Autoren: Jovan Dukanovic, Ulrich Engel, Pavica Mrazovic, Hanna

Popadic, Zoran Ziletic. Mit einem Vorwort von Rudolf Filipovic. 1986. Ln. 1510 S.

Band 11 VeIimlr Chi e b n i k 0 v 1885 - 1985. Herausgegeben von J. Holthusen t, J. R.

Doring-Smirnov, W. Koschmal, P. Stobbe. 1986. Ln. 278 S.

SLAVISTISCHE B E IT RAGE

BEGRUNDET VON AWlS SCHMAUS, HERAUSGEGEBEN

VON JOHANNES HOLTHUSEN t, HEINRICH KUNSTMANN,

PETER REHDER, JOSEF SCHRENK

Band 190 Kaltwasser, 10rg: Die deadjektivische Wonbildung des Russischen. Versuch

einer ,analytisch-synthetisch-funktionellen' Beschreibung. 1986. VIII, 235 S.

Band 191 Grbavac, Josip: Ethische und didaktlsch-aufkUlrerische "Tendenzen bei Filip

Grabovac. "Cvit razgovora". 1986. 196 S.

Band 192 Jan d a, Laura A.: A Semantic Analysis of the Russian Prefixes m-, pere-, do-, and

ot-. 1986. VlIl, 261 S.

Band 193 Bojie, Vera, Wolf Oschlies: Lehrbuch der makedonischcn Sprache. Zweite,

erweitertc und verbesserte Auflage. 1986. 252 S.

Band 194 Wett, Barbara: ,Neuer Mensch' und ,Goldene Mittelmafligkeit'. F. M. Dostoevskijs Kritik am rationalistisch-utopischen Menschenbild. 1986. VlIl, 238 S.

Band 195 Sc h mid t, Evelies: Agypten und agyptische Mythologie - Bilder der Transition

im Werk Andrej Be!yjs. 1986. 439 S.

Band 196 Ketchian, Sonia: The Poetry of Anna Akhmatova: A Conquest of Time and

Space. 1986. VIII, 225 S.

Band 197 Zeichen und Funktion. Beitrage wr asthetischen Konzeption Jan MukafovskYs.

Herausgegeben von Hans G i1 nth e r. 1986. X, 207 S.

Band 198 Kramer, Christina: Analytic Modality in Macedonian. 1986. X, 177 S.

Band 199 Egg el i n g, Wolfram: Die Prosa sowjetlscher Kinderzeitschriften (1919-1925).

Eine Themen- und MOIivanaiyse in bezug auf das BiId des jungen Protagonisten. 1986. X, 506 S.

Band 200 Siavis!ische Linguistik 1985. Referate des XI. Konstanzer Siavistischen Arbeitstreffens Innsbruck 10. mit 12. 9. 1985. Herausgegeben von Renate Rat h may r. 1986. 326 S.

Band 201 Berger, Tilman: Wortbi1dung und Akzent im Russischen. 1986. VIII, 373 S.

Band 202 Hock, Wolfgang: Das Nominalsystem im Uspensklj Sbornik. 1986. VI, 179 S.

Band 203 Wei d n e r, Anneliese: Die russischen Obersetzungsaquivalente der deutschen

Modalverben. Versuch einer logisch-semantischen Charakterisierung. 1986. 340 S.

Band 204 Lempp, Albrecht: Miee. 'To Have' in Modern Polish. 1986. XIV, 148 S.

Band 205 Ti m ro t h, Wilhelm von: Russian and Soviet Sociolinguistics and Taboo Varieties

of the Russian Language. (Argot, Jargon, Slang, and "Mat".) Revised and Enlarged Edition.

1986. X, 164 S.