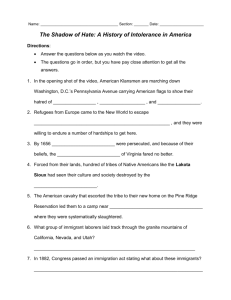

A.J. Ceberio Sustainable Corporations Final Paper

advertisement

A.J. Ceberio Sustainable Corporations Final Paper Ford v. Ford Abstract On February 7, 1919, the Michigan Supreme Court released one of the most wellknown business law decisions in American legal history. For the past century Dodge v. Ford Motor Co. has created an epic battle among legal scholars. On its face, the case stands for the principle of shareholder wealth maximization; I would argue that Henry Ford was never truly fighting with the Dodge brothers, but rather the case’s caption should have read Ford v. Ford. When I began drafting this paper, my provisional title was “Beating the Dead Horse that is Dodge v. Ford Motor Co.” I had intended to harp on than fact that many students—myself included—hate this case. We read it, think we understand it, then reread it and scratch our heads. To make matters worse, we then turn to generation y’s best friend, “Google,” only to find hundreds of articles debating whether or not the case is even good law. My intention was to discuss the specifics of the case under current laws, but after completing several drafts I recognized that my paper was simply a recreation of the thoughts of others. In my opinion, the most important question is why Henry Ford lost all those years ago. In this paper I will discuss the history of Henry Ford himself, the history of the Ford Motor Company, and finally how arrogance and/or ineffective counsel led to the outcome in court. Although I suggest that the odds were stacked against Ford, I believe that it was possible for him to come out on top. The History of Henry Ford In order to understand what ultimately happened in Dodge v. Ford, we must begin with a brief history of Henry Ford himself. Henry Ford was born on a farm in Michigan in 1863. As a young child Ford did not express an interest in farming but rather enjoyed building water wheels and steam engines. At age 16 Ford took a position as an apprentice with the Michigan Car Company working on railroad cars. After bouncing around for a few years—learning all that he could along the way— Ford returned to the farm. This time, instead of working on water wheels with his childhood friends, Ford began servicing portable steam engines for farmers. During that time Ford also held several odd jobs including cutting and selling timber and working in factories. Although Ford had 1 not developed a definitive career path, one thing was becoming clear; Ford did not like taking orders from anyone else. In 1891, Ford took a position with the Edison Electric Illuminating Company in Detroit. He knew nothing about electricity, but it only took him five years to become chief engineer. While at Edison, Ford convinced the company’s president to allow him to use a workshop to create a self-propelled vehicle. In return, Ford gave the company’s president a small equity stake in the prototype. In 1896 Ford and a group of friends completed their first prototype, the “Quadricycle.” The Quadricycle, shown in the image to the left, was a step in the right direction, but was in need of improvements. It was steered with a tiller, had only two speeds and no reverse. Ford then turned to investors to assist with the production of his second prototype. In 1899, Ford completed the second prototype. This time the finished product was significantly more polished and attracted the attention of several investors. A wealthy venture capitalist named William Murphy took an interest in the prototype and conducted an 80-mile test drive. After a successful day on the road, Murphy agreed to fund Ford and organize the Detroit Automobile Company. Murphy convinced his wealthy friends to invest in the company providing Ford with the resources he needed in exchange for significant shareholder equity. At the time, Ford had no money, but had the mechanical skills. As such, he did not contribute any capital to the company, but was given only a minority interest. At the time, this may have seemed like a good deal for Ford, but it would ultimately lead to the peril of the Detroit Automobile Company. He was always improving the design of the prototype and was reluctant to send it through to the production phase. This quickly made the majority shareholders agitated. It would likely follow that the majority shareholders would then begin to insert their own board members and supervisors to push Ford. As we have already discussed, Ford learned at a young age that he did not like listening to others, and this was no different. Ultimately Ford refused to comply with the majority shareholders’ wishes, and the company was dissolved in 1901. Although the Detroit Automobile Company was dissolved, the prototype and Ford’s vision remained. Ironically, Murphy, the man who provided the funding for the Detroit Automobile Company continued to support Ford. He was willing to give Ford more time with less pressure. Together they formed the Henry Ford Company in November of 1901. Ford had learned that he did not enjoy holding a minority interest, but that did not change the fact that he needed money. This time Ford again agreed to a minority interest—although significantly larger than before—in return for capital contributions. Unfortunately, the new company was even worse for Ford. He was already hesitant, to say the least, about being a minority shareholder, and this time he was the minority shareholder of a company that had his name on the door; it only took three months for Ford to quit. 2 Henry Ford was quite possibly the best historical example of a person that was either loved or hated. By all accounts he was anti-Semitic, arrogant and stubborn; yet he was generous, philanthropic and a visionary. It is interesting that Ford is not the only corporate executive to be described with these words. In fact, it is fascinating to compare Ford with Apple’s former chief executive officer, Steve Jobs. Like Ford, Jobs was often described as “harsh, arrogant, unkind and impatient.” On the other hand, many loved Jobs as his contributions to world were numerous. Some have gone so far as to call Jobs the Ford of our time. The greatest similarity between Ford and Jobs was their ability to understand consumers and market existing products. Just as Ford did not invent the automobile, Jobs did not invent the computer or the smartphone; he helped make them better and marketed them in a new way. It was no secret that Ford had a deep hatred of board members—whom at the time held their positions solely by virtue of their ownership interests—viewing them as “elitists and speculators who knew nothing about machines, cars, or manufacturing.” Ford was vocal about his distrust and hatred of elitists and Jews. In an interview he said, “The Jew is a mere huckster, a trader who doesn’t want to produce, but to make something out of what somebody else produces.” It was not just board members that Ford disliked; it was all investors. Ford viewed them as “parasites.” Again, it is important to understand his reasoning. Right or wrong, Ford was fed up with answering to others. He had big ideas and was tired of being held back. Most people believe that Ford simply preferred those who made things over those who made money off of those that actually put in the hard work. I think the motive is more innate than that; Ford was jealous. He was a gifted engineer with visions that most people could not dream of. Unfortunately, businesses need two things to succeed: a good idea and money. Ford only had one of the two. He was forced to take the money of others and subordinate his interests to theirs. As a result, he was taking orders from people whose only contribution was money. Ford had a difficult time coping with this dynamic, but a century later it seems capitalists still call the shots. Ford Motor Company By Christmas of 1901 Ford had learned that he truly could not work under the control of others. He was quoted as saying, “From here in, my shop is always going to be my shop… I’m not going to have a lot of rich people tell me what to do.” Unfortunately, Ford was still forgetting about a very crucial piece; he needed money! In early 1902, Ford partnered with Alexander Malcolmson. Malcolmson agreed to provide Ford with the resources he needed to create another prototype, but to allow Ford to run the show. This time Ford had a different plan. In the past Ford had built excellent prototypes, but when it came down to it, he could not stop tinkering long enough to send them through to production. As a result, Ford made the decision to outsource the 3 manufacturing process. The process would work beautifully, and in just one year Ford had his best prototype yet, ten new investors, and he and Malcolmson started the Ford Motor Company. Although I find it to be significant, scholars do not often discuss the Dodge’s path to ownership. The Dodge brothers were originally contracted by Ford to build the engines and transmissions for the prototype, but by virtue of Ford’s inability to make timely payments on the notes for the purchased engines, the Dodge brothers were given a 10% interest in the company. I purpose that Ford hated the Dodge brothers’ demands even more than he hated typical elitists. Elitists made money by investing money; the Dodge brothers procured ownership interest in the Ford Motor Company by default. Within a short amount of time, the Ford Motor Company became incredibly profitable. It was paying dividends that were almost incomprehensible. In 1904, just one year after the Ford Motor Company came into existence, the company made profits of $300,000 paying dividends of nearly $100,000. In 1910 the company made $4.5 Million in profits distributing $2 Million in dividends to its shareholders. The annual dividends continued to grow each year and in 1915 amounted to $16.2 Million on profits of $24.6 Million. To put these numbers in perspective, the Dodge brothers owned 10% of the Ford Motor Company. Their capital contribution was $10,000. That means that their dividend in 1904 repaid their initial investment in full. Their dividend in 1905 provided them of a return of 100% within two years. Over the course of the first 13 years of the Ford Motor Company, the Dodge brother’s investment of $10,000 returned more than $35 Million. The Lawsuit The issue that led to this suit came about in 1916. During that year the Ford Motor Company made $60 Million in profits but decided to pay only $3.2 Million in dividends. Instead, Ford decided to put 95% of the profits back into the company in order to increases wages and build a new factory known as the River Rouge factory. The new factory would feature innovative technology, such as a new method for manufacturing iron and would employ thousands of additional workers. According to Ford, the factory was necessary to meet demand as he expected to nearly double the number of sales from 1916 to 1917. The Dodge brothers filed suit seeking an injunction on the construction of the River Rouge factory and a court order for the payment of special dividends. The Dodge brothers won at the trial court level, and Ford timely appealed. 4 The Michigan Supreme Court faced two issues on appeal. The first was the injunction on the construction of the River Rouge factory. With regard to the injunction the court was overturned and the injunction was lifted. Ultimately the factory was built and remains one of the largest automobile manufacturing plants in the world. (A photograph of the plant is found to the right) The second issue on appeal—and the one that we continue to argue about—was Ford’s decision to not pay special dividends and to reinvest the earnings in the company. The court stated “[t]he management of the corporation and its affairs rests in the board of directors, and no court will interfere or substitute its judgment so long as the proposed actions are not ultra vires or fraudulent. They may be ill advised, in the opinion of the court, but this is no ground for exercise of jurisdiction. The board has full power over the matter of investing the surplus and as to dividends so long as they act in good faith.” They court continued that “[t]he judges are not business experts,” and stated “[t]he experience of the Ford Motor Company is evidence of capable management of its affairs.” Although the phrase does not appear within the court’s opinion, today we know the standard the court applied to be a variation of the “business judgment rule.” Under this standard, a court will not second-guess the decisions of a director as long as they are made (1) in good faith, (2) with the reasonable belief that they are acting in the best interests of the corporation. The key elements of the rule are “good faith” and “reasonable belief.” The existence of those two terms creates a very low bar for directors to overcome. Typically, in corporate law, when you see the court say the phrase “business judgment rule” you can nearly stop reading because it is extremely likely that the directors will not be found at fault. However, here the Michigan Supreme Court focused on “good faith” and came out the other way. So, why did this court use all of the right language, but come out the other way? Contrast in Opinions Throughout this paper I have made and will continue to make reference to other scholars. As discussed, this case has been debated for nearly a century; thousands of legal minds have formed their own opinions of the case. Although I may not refer to each of them individually as we continue, I would like to address three significant articles before I propose my theory. Professor Lynn Stout published an excellent article titled Why We Should Stop Teaching Dodge v. Ford. In her article Stout suggests that the justices of the Michigan Supreme Court simply got it wrong. She argues that Dodge v. Ford Motor Co. is “bad 5 law.” Stout takes it a step further to say that the court discussed maximizing shareholder wealth in dicta and its ultimate holding was that Ford breached his fiduciary duty to the Dodge brothers. Finally, although she argues that the court’s holding related to fiduciary duties, she alleges that his breach extended far beyond the refusal to pay special dividends. Overall I do not disagree with much of what Stout proposes. I believe the crux of her argument is that the Michigan Supreme Court had it in for Ford and used legal creativity to hold in favor of the Dodge brothers. However, I believe Stout and I arrive at this notion in different ways. My abstract may suggest that I agree with the idea that this case should not be taught in law school, but that could not be further from my opinion. In fact, this case has provoked more thought and reflection than any other I have encountered thus far. The next article I would like to address is titled Narrative and Truth in Judicial Opinions: Corporate Charitable Giving Cases. Geoffrey Miller poses the theory that an inherent issue occurs concerning the accuracy of the mapping between the underlying facts and the description of those facts in a court’s opinion. I understand Miller’s argument to be analogous to the “telephone game.” Most of us recall playing the telephone game where the phrase is never the same at the end of the line as it was when it was first said. According to Miller, it is inevitable that the events and facts will be distorted by the time a decision is released. He attributes the distortion to a multitude of factors including recollection, partial disclosure, and framing. Miller contends that the Michigan Supreme Court in Dodge v. Ford Motor Co. failed to reference the fact that neither party wanted to acknowledge what the case was really about. It is interesting that Miller does not make any assertion as to whether the Michigan Supreme Court got it right or wrong but simply argues that they did not focus on what was important. I agree with Miller entirely. I fully believe that the real reasons for Ford’s decision to refrain from paying a dividend was not discussed in the opinion. However, the thesis of this paper focuses on the facts the court did articulate and how they may have led to a different result. Finally, I would like to address an article written by Todd Henderson titled Everything Old Is New Again: Lessons Learned from Dodge v. Ford Motor Company. A large proportion of Henderson’s article focuses on how many of the practices common today in venture capital transactions played a key role in Dodge v. Ford Motor Co. I must admit that I thoroughly enjoy Henderson’s article and find his thesis fascinating. Essentially Henderson believes that this case was several decades before its time. He recognizes that under modern corporate law Ford would have certainly come out on top. Furthermore, he points out that the Michigan Supreme Court decided to make a statement by chastising Ford’s comments. Henderson believes the court chose to rule as it did because it feared the road it would pave by allowing Ford to forego dividends in light of the comments he made at trial. Overall, I find my theory to be most similar to Henderson’s. I would agree that the court required ammunition to rule as they did, but I do not think they were worried about the message they would be sending. 6 Henry Ford’s Counsel, or Lack Thereof As previously discussed, Ford was arrogant and loud mouthed. He had a reputation as an anti-Semitic and a deep hatred of elitists. Although he was seen as a philanthropic employer—or as the Michigan Supreme Court would put it, semieleemosynary—he was disliked by many. There is little doubt that the justices did not want to see Ford win this case. Some scholars think it is because they feared how influential he had already become, while others think they just didn’t like him. Some would go as far as saying that Ford was going to lose this case no matter what. I am skeptical about that assertion. Whatever the underlying motivation, with the application of the business judgment rule, Ford needed to give them ammunition. Without something to fall back on, the court had no choice but to allow Ford to decide to reinvest the dividends. This is where Ford’s arrogance and the ineffectiveness of his counsel come in. One of the innovative things Ford planned to do at the River Rouge plant was to change the way they produced iron. He was asked about this change, along with many other aspects of the operation of the Ford Motor Company. The following is an excerpt from the cross-examination of Henry Ford at trial: Counsel: Ford: Counsel: Ford: Counsel: Ford: Counsel: Ford: Counsel: Ford: Counsel: Ford: Tell us, let us know about your new scheme? I did start to tell you a little while ago. If I stopped you, start again. Yes. We are going to make iron out of ore, directly out of ore, melted of out or ore, and we are going to use it to cast our cylinders, and our castings, and use our scrap, and use our material up, and to make the castings directly from the ore; and we are going to get uniform castings, which has never been got where we melt pig iron in eleven or twelve cupolas at the factory. We take the pig iron and mix it with something, mix it with our borings, and stuff, and we never get a uniform casting. We have a great waste, and a great loss, from our castings, because the cupolas are a very poor thing to melt iron in. The wrought iron comes down first, and we never get a uniform casting. In this new scheme, we are going to melt the iron directly out of the ore, and run it into a mixer, and we are going to get a uniform mixture with proper analysis, and turn it directly right into castings right there, and save a great deal of money by doing it, reduce the cost of the car, and get an absolutely strong iron metal. Who is doing that sort of thing now? Nobody. Nobody? No. You are going to experiment with the Ford Motor Company’s money, to do it, are you? We are not going to experiment at all; we are going to do it. Nobody has ever done it? That is all the more reason why it should be done. 7 Counsel: Ford: Counsel: Ford: Counsel Ford: Therefore, you are going to undertake to do something that nobody else has done, that nobody else have even tried to do? Oh, certainly. There wouldn’t be any fun in it if we didn’t. You are going to find some fun in it? Yes, certainly. But at the expense of the Ford Motor Company? That is all I am working for at the present time, is to have a little fun, and to do the most good for the most people, and the stockholders. … Counsel: Ford: Counsel: Ford: Counsel: Ford: Counsel: Ford: Do you still think those profits were awful profits? Well, I guess I do, yes. And for that reason you were not satisfied to continue to make such awful profits? We don’t seem to be able to keep the profits down. Are you trying to keep them down? What is the Ford Motor Company organized for except profits, will you tell me, Mr. Ford? Organized to do as much good as we can, everywhere, for everybody concerned. And incidentally to make money. Incidentally to make money? Yes, sir. The testimony above can lead us to believe one of two things: (1) Ford’s counsel did not prepare him in any way whatsoever for trial; or (2) Ford was so arrogant that he refused to take the advice of his counsel. Either way, it is hard to imagine a director giving more damaging testimony at trial. In its opinion, the Michigan Supreme Court stated that Ford “has to some extent the attitude towards shareholders of one who has dispensed and distributed to them large gains and that they should be content to take what he chooses to give.” It is debatable whether the court would have made this assertion absent Ford’s testimony. Many scholars suggest that without this testimony, the court would have considered Ford’s out of court statements and come to the same conclusion. Again, I am skeptical. As we now understand the rules of evidence and civil procedure, the court would have had no right to include this finding in its opinion. It is an entirely different argument, one that is not within the scope of my thesis, whether the court may have chosen to act outside the boundaries of the law. Ford needed to take the stand and explain how the decision to withhold special dividends benefitted the Ford Motor Company in the long run. In reality he did the opposite. In his testimony he explained that he was trying to keep profits down and do good for everybody, incidental to making money. Further, instead of saying he was going to explore with a new method of iron production for the fun of it, he could have said that their analysis concludes that developing this new method would yield lucrative results for the company pushing them even further in front of their competitors. I fully understand the stacked deck against Ford, but fail to accept that the Michigan Supreme Court would 8 have been able to rule against Ford if he had demonstrated a good faith belief that his strategy was in the best interest of the corporation. In order to demonstrate the low standard of the business judgment rule, I offer the well-known Illinois Court of Appeals case, Shlensky v. Wrigley. In Shlensky the president of the Chicago Cubs refused to install lights at Wrigley Field. The lack of lights meant that the club could not host night games, which in turn led to reduced profits for shareholders. It would logically follow that the shareholders would file suit against the president in order to compel him to install lights. According to the president, baseball was a “daytime sport.” In addition, he believed that the installation of lights, and thus the existence of night games, would have a negative impact on the surrounding neighborhoods. This argument is flimsy to say the least. However, the president had one thing on his side; no one accused him of acting in bad faith. He displayed a good faith belief that the refusal to install lights was in the best interest of the organization. As such, the Illinois Court of Appeals—properly applying the business judgment rule—held in favor of the president. Conclusion Scholars have been arguing over the holding in Dodge v. Ford for nearly a century. Some think that the court simply did not want Ford to win. Although I would agree with that notion, I do not think that the justices could have ruled that way without help from Ford. It is possible that the Michigan Supreme Court would have found another reason to rule against Ford, a notion that has been recognized in may articles, but as those reasons were not articulated in the court’s opinion I have chosen to refrain from discussing them herein. Under the business judgment rule, although it was not so eloquently named in 1919, all a director must exhibit is a good faith belief that that the decision is in the best interest of the company. In this case it would have been easy for Ford to say that he was reinvesting the profits in order to build a new factory, which would increase production and yield exponentially greater returns for the company in the long term. Unfortunately, Ford’s arrogance—or lack of awareness of the law—led him to give what may be the worst testimony ever given by a business director. It would have been interesting to see how this case would have come out if he had simply hired the attorney from Shlensky. 9