Securities Fraud Defendants Aiding and abetting “Primary violator”

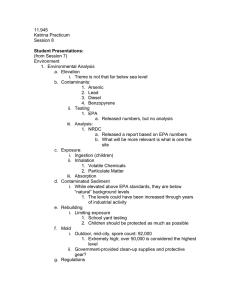

advertisement

Securities Fraud Defendants Aiding and abetting “Primary violator” Control perons (last updated 24 Apr 12) Central Bank v. First Interstate (US 1994) Bond investors sue Central Bank (indenture trustee) bonds Annual report Underwriter Board of directors Public Building Authority (Issuer) AmWest (developer) appraisal Assessment liens Holding: “… statutory language, ‘the starting point in every case involving construction of a statute.” Any person or entity, including • We presume Congressorwould a lawyer, accountant, bank, have used the awords “aid” and who employs manipulative “abet” device or makes a material • Statute prohibits only the misstatement (or omission) on making a material misstatement which a purchaser or seller of (or omission) securities relies may be liable • [Other liability provisions under ’33 do notviolator include … aiders as Act a primary and abettors] • Allowing the plaintiff to circumvent the reliance requirement would circumvent the careful limits on 10b-5 recovery Justice Anthony Kennedy Apply Central Bank … Central Bank v. First Interstate (US 1994) Bond investors sue Central Bank (indenture trustee) bonds Annual report Underwriter Board of directors Public Building Authority (Issuer) AmWest (developer) appraisal Assessment liens Press Release: The company is today announcing its year-end financial results, which continue to look favorable. *** • Auditor – Release omits to state that auditor has doubts about financials, which are not audited – In fact, no mention of auditor, which had advised that financials actually “NOT favorable” • Lawyer – Release omits to state that lawyer who helped draft the press release aware that results unfavorable – In fact, no mention that lawyer threatened a “noisy withdrawal” Scheme liability … Stoneridge Inv v. Scientific-Atlanta (US 2008) Purchasers (Stoneridge) Quarterly reports Executives Charter Communications (Issuer) Arthur Andersen (Auditor) Book ad revenue Capitalize boxes Sham transactions box purchases advertising Scientific-Atlanta Motorola (customer/suppliers) Holding: Reliance by plaintiff upon the defendant’s deceptive acts is an essential element of the S 10(b) private cause of action. [Reliance excused only when duty to disclose or fraud on market.] [If assume reliance by investors on transactions that financials reflect, 10b5 liability] would reach the whole marketplace in which the company does business, and there is no authority in the rule. The suppliers deceptive acts are too removed to satisfy the requirement of reliance. [See federalism concerns; Congress extends aiding and abetting only for SEC; practical consequences.] Justice Anthony Kennedy Makers of statements … Janus Capital v. First Derivative (US 2011) Investors Shareholders sue Prospectus writes Janus Capital Group Board of Trustees Janus Investment Fund (Issuer) Services (permits market timing) Janus Capital Mgmt (Investment Adviser) Rule 10b-5 -- Employment of Manipulative and Deceptive Devices It shall be unlawful for any person, directly or indirectly, by the use of any means or instrumentality of interstate commerce, or of the mails or of any facility of any national securities exchange, (1) To employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud, (2) To make any untrue statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading, or (3) To engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person in connection with the purchase or sale of any security. Holding: Is JCM liable for false statements in Fund prospectus? No One “makes” a statement by stating it. … One who prepares or publishes a statement on behalf of another is not its maker. [Speechwriter / speaker] … the maker of a statement is the entity [ legally independent Fund] with authority over the content of the statement and whether and how to communicate it. The [SEC’s] definition would permit private plaintiffs to sue a person who “provides the false or misleading information that another person then puts into the statement.” [drafting same as engaging in deceptive transactions] Justice Clarence Thomas Section 20 (a) Every person who, directly or indirectly, controls any person liable under any provision of this title or of any rule or regulation thereunder shall also be liable jointly and severally with and to the same extent as such controlled person to any person to whom such controlled person is liable, unless the controlling person acted in good faith and did not directly or indirectly induce the act or acts constituting the violation or cause of action. Control person liability … Lustgraaf v. Behrens (8th Cir 2010) Section 20 Investors (a) Every person who, directly or indirectly, controls any person liable under any provision of this title or of any rule or regulation thereunder shall also be liable jointly and severally with and to the same extent as such controlled person to any person to whom such controlled person is liable, unless the controlling person acted in good faith and did not directly or indirectly induce the act or acts constituting the violation or cause of action. 1. Behrens is primary violator 2. SF “actual control” of Behrens 3. SF “power over specific acts” of Behren Ponzi scheme Behrens Sunset Financial Kansas City Life Insurance The end Wright v. Ernst & Young (2d Cir 1998) Shareholders Press release (financials) reviewed Ernst & Young (Auditor) Executives BT Office Products (Issuer) assured Arthur Children’s Trust v. Keim (9th Cir 1993) Section 20 Investors (a) Every person who, directly or indirectly, controls any person liable under any provision of this title or of any rule or regulation thereunder shall also be liable jointly and severally with and to the same extent as such controlled person to any person to whom such controlled person is liable, unless the controlling person acted in good faith and did not directly or indirectly induce the act or acts constituting the violation or cause of action. notes Joint venture Keim • D of Santa Fe • member Mgmt Comm • 10% equity owner • not recruiter Santa Fe Company Parkland Development • • • • "Scheme Liability: A Reply to Grundfest" McCombs School of Business Research Paper ROBERT A. PRENTICE, University of Texas at Austin - McCombs School of Business Email: rprentice@mail.utexas.edu This paper responds to Professor Joseph Grundfest's recent paper opposing recognition of scheme liability under §10(b)/Rule 10b-5 Scheme Liability: A Question for Congress, Not for the Courts. In responding to Professor Grundfest's cogent arguments, this article tries to simplify the issue. Section 10(b) is indisputably valid, and it broadly authorizes the SEC to issue rules to protect the investing public from fraud. The Commission issued Rule 10b-5, using Congress's own words from the antifraud provisions of the 1933 Act, including the scheme to defraud language. No one suggests that Rule 10b-5 is invalid, so that should largely end the debate. A valid agency rule that Congress authorized expressly outlaws schemes to defraud in the sale of securities. Q.E.D. It may be telling that Professor Grundfest's paper neither quotes §10(b) (or Rule 10b-5) nor sets forth the facts of the case. As other opponents of scheme liability, Professor Grundfest tries to divert attention from the wording of the statute and rule to the holding in Central Bank. However, Central Bank did not address scheme liability or the proper scope of primary liability under §10(b). It held only that there is no express cause of action for aiding and abetting liability, with the Court stressing the absence of aiding and abetting language in §10(b)/Rule 10b-5. However, the necessary language for scheme liability is present in §10(b)/Rule 10b-5. The Supreme Court has properly noted that divining what Congress would have intended in 1934 often requires historical reconstruction. Such a reconstruction clearly demonstrates that Congress in 1934 would have expected joint tort liability to be visited upon those who knowingly participated in a fraudulent scheme to sell securities. The scheme liability language of Rule 10b-5 was borrowed from Congress's own words in §17(a) of the '33 Act which, in turn, were derived from the federal mail fraud statute. Case law under both that statute and the common law of fraud (to which the Supreme Court has also looked for guidance in interpreting §10(b)) indicate that in 1934: (a) all who knowingly participated in fraudulent schemes were held liable (with no distinction being made between primary and secondary liability), and (b) liability was consistently imposed in cases that are nearly identical factually (A knowingly participates in B's fraudulent scheme by entering into a fake transaction that enables B to defraud C) to recent scheme liability cases, including the Stoneridge case currently before the Supreme Court. Much of Professor Grundfest's article is, in stark contradiction to his title, composed of policy arguments that should be largely irrelevant to the Supreme Court's determination of Stoneridge. These policy arguments apply equally to the misrepresentation and manipulation provisions of §10(b)/Rule 10b-5, which are indisputably valid.