Griffin 1

advertisement

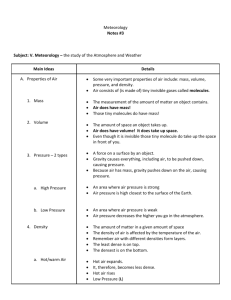

Griffin 1 The Tiny House Movement: An Overview of An Efficient Housing Solution Abstract With energy and resource prices rising, savings falling, and population growth and global climate change looming, the “tiny house movement” may be a solution to housing needs both in the United States and globally. The tiny house, a term for a wide array of smaller-than-average dwellings, provides economic, energy, and environmental efficiency for its owners in the face of societal change brought on by economic and environmental crises. The dwelling’s designs and materials range from traditional cottages to minimalist statements, from wood and nails to tempered steel and plastic. Tiny house ownership is just as varied and growing in a continually expanding online community. However, these houses still face challenges in land usage and zoning regulation, building codes, loan financing, and cultural backlash. As the movement continues to grow, these challenges are being confronted. If present economic and environmental courses continue, these same obstacles will likely be overcome to incorporate efficient housing solutions like the tiny house into the world at large. Introduction Small rooms or dwellings discipline the mind, large ones weaken it. -Leonardo Da Vinci Due in part to recent environmental and economic turmoil, a renewed discovery of small dwellings has been the focus of many minds in the United States. Over the past few decades, the “tiny house movement,” a mostly online community focused on creating, selling, and living in these dwellings, has grown. Although they face obstacles in law, finance, and cultural stigma, the movement continues to grow today and more people are finding it beneficial and even necessary to simplify their living arrangements in the name of efficiency. Undoubtedly, as the same economic and environmental uncertainties continue, this movement will likely provide at least one solution to the growing problems of debt and sustainability facing homeowners. This paper endeavors to provide an overview of the tiny house movement, the benefits generally derived by tiny house owners, and the drawbacks faced by the movement, in order to give a more complete picture of one possible solution to the problem of efficient, affordable housing for a growing population. What is the Tiny House Movement? Background to the Movement From 1950 to 2000, the average house size doubled from 989 to 2000 square feet. GreenBiz. From 2000 to 2012, the growth continued, to 2400 square feet. Behind The EverExpanding American Dream House: NPR. And despite economic recession, the number of building permits in 2013 was the highest it had been in 5 years. Bloomberg. What can account for these obvious changes? Families are certainly not growing - the average number of occupants of these houses dropped during the same period, 1950-2000, from approximately 3.6 to 2.6 people per household. Griffin 2 Average American Household Size 1948-2012, Courtesy of MarketingCharts.com On the economic side of the issue, as of October 2013, the median price for a new house was $245,800. NAHB. The average American, however, is $225,238 in debt, about three fifths of which is a mortgage. With a median income of $40,000, the average American cannot pay for a new house without going into decades of debt. Energy prices have also continued to rise, as has consumption of energy in the household. EIA. Despite the growth in house size and economic and energy expenditures per person, there does not seem to be a logical connection between this growing consumption and its increasing costs. What is the Tiny House Movement? The Tiny House Movement, to quote The Tiny Life, “is a social movement where people are downsizing the space that they live in.” The focus, though, is on simplification. Even families with 4000 square foot homes are considered part of the movement, if the “space is used well.” HowStuffWorks.com. The foci of the movement include the tiny houses themselves, life simplification, environmental consciousness, self-sufficiency, sound fiscal plans, and social consciousness. The Tiny Life. The movement encompasses global membership, but its focus in the United States is due to the aforementioned rises in house size and prices, despite the cultural backlash it has experienced. Members of the movement range from college students to retirees, but the largest group comes from those over 50 years of age. Huffington Post. Membership is growing each year. The heart of the movement lies online, with hundreds of owner-builder blogs, directory listings, and small-time companies producing and improving upon tiny house designs and ideas. However, a recent development has been the creation of workshops and conferences, usually Griffin 3 culminating in the construction of a tiny home by the attendees. These conferences are frequently hosted by well-known tiny house companies, such as Tumbleweed Tiny House Company and Four Lights Tiny Houses. In fact, new conferences are being hosted every year in more unreached states, like the 2014 Tiny House Conference in Charlotte, North Carolina. Though still nascent in its modern iteration, the tiny house movement is picking up steam, due at least in part to the structures’ inherent efficiencies. However, the structures themselves need a clear definition. What is a Tiny House? Central to the movement is the tiny house itself. However, its definition is incredibly ambiguous. Even the founder of an iconic tiny house company, Jay Shafer, has not made “a definitive definition of what is small and what constitutes a tiny house.” To most it seems not so much a particular size or style of dwelling, but a deliberate choice of the occupant to reduce and simplify their lives – to become more efficient for economic, ethical, or other reasons. However, some patterns can be seen in the movement’s designs that give a clearer picture of the tiny house. Common characteristics of the tiny house include its relation in size to the 1950 average square footage, usually under 1000 square feet. They are frequently owner-built, handmade, or created by small companies. Some of these companies have gained national acclaim, like Jay Shafer’s Tumbleweed Tiny House Co., but few large corporations or home developers, apart from IKEA, a Swedish company, have begun to construct these homes in the United States. The tiny house structures can be split by size into four general categories, from largest to smallest: Cottages (up to and past 1000 sq. ft.), Classic (100 – 300 sq. ft.), Micro/Pico (under 100 sq. ft.), and Short-Term or “Wee” Shelters (even less than 100 sq. ft.). Of course, these categories can become confusing as the names are used interchangeably with differently sized structures. They are only meant as a basic framework to understand the panoply of homes and styles within the movement. Griffin 4 An Example and Floorplan of the “Micro” XS Cabin (65 Sq. Ft., not including loft), by the Tumbleweed Tiny House Company (now discontinued). A Brief History of the Tiny House Movement According to some members, the tiny house movement can be traced in its philosophical roots to Henry David Thoreau, the American writer and existentialist. His 10’ by 15’ cabin by Walden Pond and philosophy “to live deliberately” in his book Walden, is referenced by tiny homebuilders and owners as a point of inspiration for their own homes. However, others direct their inspiration back thousands of years to the creation of the Mongolian yurt or North American tipi. Tiny Houses of the Past. Still others point to the 1920s, and the advent of the American automobile, where “motor homes” were built on the newly developed car chassis. A 1929 Model-T Motor Home, Courtesy of The Old Motor Griffin 5 After the 1920s, it was not until the 1960s and 70s that the “Back-to-the-Land” movement took hold among young Americans and homes that were “anti-suburban” and “anticonsumerist” were brought back into focus. During this period, certain “tiny home” building processes and materials found their niches, such as geodesic domes, residential solar panel systems, and Earthship Biotecture – a form of home focused on recycling materials and selfsufficiency. However, each of these periods can be seen to provide only one part of a multifaceted movement. Only the modern movement, starting in the 1990’s, can be pinpointed with some accuracy. Despite confusion of its earlier roots, the beginning of the modern tiny house movement is widely accepted as the publishing of The Not So Big House by Sarah Susanka, an American architect, in 1998. The book detailed designs and the philosophies behind “living small,” and is considered to be the inspiration of the Tumbleweed and Four Lights Tiny House Companies. The Small House Society, founded in 2002, acted as an online network and database for the original small house owners and builders. From there, the movement spread online and across the country, and continues to grow today. The reasons behind this growth can be seen in the benefits of the homes: their energy, economic, environmental, and even psychological efficiencies. The Benefits of Tiny Houses Energy Efficiency Due mostly to their size, tiny houses are incredibly energy efficient. In 2012, the average monthly consumption of electricity for the residential customer in the South Atlantic region, EIA's designation for a region of states encompassing West Virginia to Florida, was 1,079 kWh. The average monthly bill for 2012 in that region was $122.71. This average cost can be compared to the Tumbleweed Tiny Home, chosen because of its relative ubiquity and uniformity. Using this model, most tiny home occupants would have utility bills that range from $10 to $35 a month. This cost includes electricity, water, sewage, and propane. In addition, many tiny houses have solar power systems built in which, if installation is not counted here, bring the electricity bill down to $0 or close in sunny regions. L.E.D. lights and energy saving appliances, common in the dwellings, draw on this energy efficiency. Even heating is frequently by wood or propane stove, which discounts further the electricity bills. Economic Efficiency Economic benefits spur most people to join the tiny house movement. According to the National Association of Realtors, the average mortgage for a new house in 2011 was "$222,261 with a $1,061 average monthly payment for a 30-year mortgage at 4 percent." This average, of course, assumes the purchase of a newly built home. However, even older homes can be double the price of a newly built tiny home. Construction costs depend heavily on labor, materials, and design, but an Elm tiny home, by Tumbleweed, purchased ready made and outfitted, is only $57,000 with 10% down with a 6% APR on a 15 year loan. This is a $433 a month payment for only 15 years compared to the $1,061 a month for 30 years. Griffin 6 Furthermore, the prices of tiny houses are expected to drop as more and more companies begin constructing their own and demand increases. For instance, a newer company, Tortoiseshell Tiny Homes, now offers finished and unfinished steel frame tiny houses with optional wind and solar power systems, for base prices of only $30,000. Competition may decrease prices even further, but the clearest economic benefits still come from ownerconstructed homes. It is not unusual to have owners build fully functioning homes for under $10,000. These homes utilize recycled and free materials, including wooden pallets, ISO shipping containers, and clay cob- a form of low-carbon construction with wet clay bricks. As an example of these low-cost measures, the home shown below was built by a single mother in California for less than $4000. A $4000 Shipping Container Home via faircompanies.com Environmental Efficiency As mentioned before, a large part of the tiny house movement is reducing the owner's carbon footprint. Due to their artisanal nature and small size, tiny homes frequently utilize much more sustainable, eco-friendly, or local materials and products in their designs than the average development home. This of course includes things like low-VOC paint (and even some milkbased paint), sustainable lumber, solar panel systems, and grey water systems. One brand new example is "Ecovative" myco-insulation that is fire-resistant, incredibly efficient, and biodegradable. The company, Ecovative, has won the first Cradle-to-Cradle design award for its product, which is composed of mushrooms and cornhusks. Its first plans for the product include placing it in a tiny home. Griffin 7 The Process for Myco-insulation from Ecovative. “Psychological” Efficiency Tiny House owners tend to list among their benefits not a "quantifiable" efficiency but a sense of organization, well being, and peace from the ability to have "just what you need" and no more. This minimalism stems very practically from the sheer lack of space for excess in tiny homes and translates, as the owners explain, to more time with family and friends as well as personal hobbies. In addition, many tiny homes are mobile, allowing for spur of the moment travel, and freedom that lies with it. Yet, in spite of these benefits, there are several challenges faced by the tiny house movement that must be overcome in order for these dwellings to flourish. The Challenges Faced by Tiny Houses Land The average home, particularly in housing developments and urban areas, is subject to a series of size minimums and other buildings codes, stemming from historic building codes and land value concerns. Unfortunately, the same codes created originally for safety and well-being of home occupants are antagonistic to tiny house design because they require a certain amount of square footage in order to achieve legal “habitable dwelling” status within the code. Mitchell, Ryan. Cracking The Code: A Guide to Building Codes & Zoning for Tiny Houses. 1st ed. 2012. 5-8. eBook. In particular, some codes require these “habitable dwellings” to have a total square footage of at least 300 to 500 square feet. Mitchell, 10. Other codes require separate sewer systems, where some off-grid tiny homes have composting toilets, and separate closet spaces. Id. Most tiny houses cannot meet these minimum size standards and are therefore considered illegal to build on developed land. In response, owners have increased their footprint to the minimum requirements, still below 1000 square feet, have built their homes on wheels, or have found loopholes in the local zoning regulations that would otherwise require larger houses or would not allow such a structure to be placed on the area. By building on a trailer, tiny homeowners take advantage of RV regulation that is more relaxed than building codes. This is partially due to the difficulty of enforcement, and the ability to park the home itself in a designated area like a campground or trailer park. However, even these RV codes require proof of mobility, fire safety, and certain size regulations. Another option is to park the finished home on a friend or relative’s land as an “enclosed trailer,” which is regulated by the Dept. of Motor Vehicles, or as “an accessory dwelling unit,” Griffin 8 which is defined by city zoning codes, but less stringently than a home. By doing so, the owners of the tiny house can gain utility hookups from the main dwelling as well as a formal mailing address, which prevents some investigation into the structure’s legality. Most tiny house owners that use this method pay their share of the utility bills each month to the landowner as well as a nominal rent fee. If the land itself is also in a rural area, there is a very unlikely chance of disruption by zoning officials, which explains the large number of rural tiny homes. For those who want to appeal to the building code system, variances can be sought and received, but these are frequently expensive, require a lengthy application and approval process, and are not guaranteed. However, working within the system can benefit other tiny house owners over time, allowing for growth of the movement in places with otherwise outdated codes. Still, the issue has yet to be settled in regards to tiny homes. Loans Banks are currently wary of loaning mortgages for tiny houses due to resale value. There is some logic to this, considering the fact that most tiny houses are illegal and built by owners with otherwise little construction experience. Therefore, most tiny houses are financed by personal credit, savings, short-term loans with friends and relatives, or by the companies selling the homes themselves. Even insurance for tiny homes is hard to find, though the idea of cooperatives among owners is growing. If the tiny house is on a wheeled trailer, RV financing is available, but the structure must be built according to RV specs, which can be exacting and localized. However, unlike land, methods of financing, if non-traditional, are actually legal are for these homes. Laws Current laws, as seen in building and zoning regulations, are not amenable to tiny house construction or ownership. A major concern is not from the laws on the books, but the enforcement of those laws by the local authorities, leading to fines and even condemnation. However, the cities with these antagonistic codes have been found to have mainly “complaintdriven enforcement,” and will not actively seek out otherwise law-abiding citizens without a formal complaint made against the homes. Further, many of these zoning boards have had to cut back staff in the wake of economic recession and are unlikely to investigate unless there is possible criminal conduct or common law nuisance in effect. These loopholes, however, are still not solutions to the “laws” problem of tiny homes. The laws still need to be changed to provide security and peace of mind for the companies and owners interested in pursuing tiny house construction and occupation. Local, state, and federal levels of government are being lobbied to change zoning laws and building codes in order to allow legal occupation and construction of the homes. On the local front, although some cities like Portland, Oregon, have provided zoning waivers for accessory dwellings and spot variances, the local powers are still closed to any ideas of “fronting” a tiny home on a residential street. Other local petitions for single homes, however, have been Griffin 9 successful on a state level. At the federal level in 2012, a petition to President Obama for federal reform of state zoning laws was passed around the tiny house community in order to gain a voice where state legislatures had been reluctant to listen. Although it gained online recognition, the petition has since expired for lack of signatures and few attempts are being made at its resurrection. Currently, then, the state of the law regarding tiny homes is tenuous, but as the movement continues to expand, there may be further, and perhaps more successful attempts at changing it. Social Stigma An ephemeral yet powerful obstacle facing the tiny house movement is that of a social stigma towards the homes themselves both from mainstream American culture and from friction within the movement itself. As already shown, American houses continue to grow, as does American debt. This expansion continues, perhaps due to ideals of “suburban manifest destiny,” or even due to increased stress in society. Regardless, the results are clear and the resulting culture can be dissuading and even hostile towards the tiny house movement. Take, for example, the recent continued construction in Orlando, Florida of a 90,000 square foot home for only ten occupants. According to Businessweek, “[the builders’ story] is a very American story…of idle consumption [and] wanton ambition.” This “very American story” can be seen to be at odds with the values presented by tiny house movement like simplicity and paring down of possessions. However, the movement has also been considered “an alternative American dream” by some sources. Although there is current unspoken friction between these two ideals, shifts in culture and economy will likely decide which values control. Versailles: A 90,000 Sq. Ft. Home in Orlando, FL via Chillopedia.com In addition to mainstream culture, there is some friction created within the movement as to what should or should not be considered part of “tiny house communities” and their culture. Questions have arisen within the movement as to elitism of some forms of tiny house living, such as a mobile home or customized RV instead of a hand-built cottage. Some members focus on sustainability while others do so on frugality. Although these divisions are disconcerting, the Griffin 10 movement continues to grow and gain national media attention, with independent new owners beginning construction without concern for these arguments. Conclusion And Thoughts on the Future In summary, the tiny house movement offers a counter-cultural way of living that provides some very clear benefits of efficiency and peace of mind. The homes are more flexible than the traditional suburban home, but have distinct drawbacks in land, loans, and laws that must be considered and remedied for their widespread use. Nonetheless, construction and occupation of these dwellings is spreading, thanks to national media, online sources, and live conferences. Depending on the outcome of economic, political, and environmental circumstances, these homes can possibly become at least one solution to a growing housing problem experienced in the United States. If not for full-time residences, other suggestions have been made for their use including college dormitories, homeless shelters, small-scale business space, and even disaster relief. One thing is for certain, however, these future small dwellings will likely make a big impact.