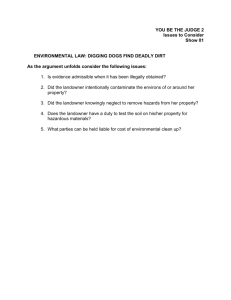

Improving the position of the Landowner under the Traditional Oil... Lease in the United States.

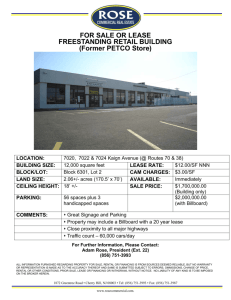

advertisement

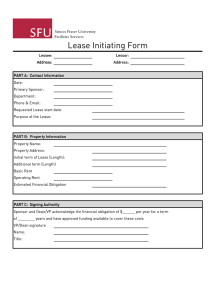

Improving the position of the Landowner under the Traditional Oil and Gas Lease in the United States. What is an Oil and Gas Lease? An oil and gas lease is a distinct legal document that grants an oil company (or “lessee,”) the right to extract oil, natural gas and occasionally “other minerals” from the property of a landowner. In return, the land that the owner would generally not have had the capital or expertise to develop, receives consideration in the form of bonuses, royalties and rental delay payments. See, Landowners’ Rights. In general, the oil and gas lease addresses three topics: the duration of the grant (habendum), the interests granted to the oil company and the landowner’s consideration. Other clauses within the lease either expand or limit the above topics. See, Modern Oil and Gas Lease. The lease’s distinct nature has been described by critics as “both a conveyance and a contract.” See, Oil and Gas Lease and ADR. It conveys the principal exploration and development rights to an oil company, whilst contractually burdening such a conveyance through express and implied covenants. See, Gulf Oil Corp. v. Southland Royalty Co. (Tex. 1973). Its distinct nature has evolved through many years of volatile court decisions, particularly in Texas, which attempted to give effect to the parties’ intentions. Consequently, such precedent transformed, and continues to transform, the form of the oil and gas lease in the United States. See, McFarland’s Checklist. As such, there is no “standard” form for oil and gas transactions, so all leases are, in theory, negotiable. See, Landowners’ Rights. However, large, independent oil companies were able to draft forms that highlighted some fixed, essential terms of an oil and gas lease, known as the “Producers 88.” The major drawback of such a broad transfer of rights is that the “Producers 88” is drafted in favor of the oil company, at the expense of the individual landowner. See, Exhibit A, attached. Landowners should therefore be wary when acting independently and should seek to add “riders” or “addendums” to their lease to override the contrary lease stipulations employed by oil companies. See, McFarland’s Checklist. In addition, landowners should always seek to enforce oil and gas’ implied covenants, such as reasonable development of land. Authorities disagree on whether these covenants are implied by the terms of an oil and gas lease itself and are used by courts to affect the will of the parties or whether these covenants are implied by law and used by courts to promote fairness and equity. Either way, implied covenants have been able to act in the landowner’s favor for over one hundred years. See, Implied Covenants. However, landowners should be aware that oil companies have recently been able to circumvent such implied protections by expressly excluding their application in the lease. This “Question and Answer” therefore seeks to make landowners aware of the many ways in which they can “offset the one-sidedness of industry lease forms” through additions to, or removal of, certain standard provisions. See, YouTube: Tips for Landowners at 14 minutes, for more information on the negotiating power of landowners. What is the typical duration of an Oil and Gas Lease? In the past, oil companies leased land over a short period of time, as they believed that immediate extraction had to occur before any oil and gas “escaped.” See, Oil and Gas Lease and ADR. However, once oil companies learnt more about the geological composition of oil and gas and the commercial pragmatism of future development, the duration of leases were curtailed into a short primary term, followed by an indefinite secondary term. See, Economics of Oil and Gas Law. The primary term is usually a specified number of years, between two and ten, where as long as production or exploration of oil and gas occurs before the end of its term, the lease is upheld. The “habendum” clause then extends the primary term into its secondary term “... for a term of _____ years and as long as oil and gas, or either of them, are produced.” See, 6 West's Tex. Forms, Minerals, Oil & Gas § 3:2 (4th ed.,) (available on Westlaw.) However, the development of the duration of the lease term has a number of limitations. The key hindrance of the primary term for the landowner is negotiating down the ideal, extended period of around five to ten years of the oil company. The oil company favors such a lengthy approach as they lease land elsewhere “at a pace that exceeds their ability to produce.” The problem for the landowner therefore is the delay in receiving their royalties. Additionally, if no production at all occurs at the end of the extended primary time period, the landowner will only have received the initial bonus payment (and potentially nominal delay rentals) and severed the interests of any other interested oil companies. See, Common Issues. Lastly, as the lease can be terminated during the primary term in the event that production is no longer profitable, landowners are at risk from oil companies failing to fulfill leases due to the rapidly changing market conditions of the oil and gas industry. See, Contracts as Fences. As such, Pierce has suggested that lease profitability should therefore be assessed as an average over the primary term, to take into consideration the effect of changing prices on landowners. See, Modern Oil and Gas Lease. Such a suggestion would work well alongside the proposal of many lawyers who argue that landowners should insist on a shorter primary term of one to three years, as it would decrease the likelihood of being affected by the shifting market. See, Contracts as Fences. Perhaps the most serious disadvantage of the duration of the lease term however falls under the “habendum.” As can be seen from the habendum above, the lease is only held in effect at the end of the primary term “as long as oil and gas, or either of them, are produced.” Many commentators have therefore argued that there is “no guidance” for the landowner as to what form of production will suffice to allow a progression into the indefinite secondary term of the lease. See, Economics of Oil and Gas Law. Texas requires production in “paying quantities” at the end of the primary term, otherwise the lease will terminate. Such “paying quantity” relates to the profit after the cost of production. See, 6 West's Tex. Forms, Minerals, Oil & Gas § 3:2 (4th ed.,) (available on Westlaw.) Oil companies in other states however have attempted to overcome potential lease termination by stating in the “Producers 88” that as long as production “operations” are in place under the primary term, the oil company can progress with the lease. The key problem with an inclusion of “operations” is that it is not specific enough. Does an existing well that has ceased to produce oil and gas suffice as “operations?” See, McFarland’s Checklist. As highlighted in Exhibit A’s “Primary Term” (subsection 2), specifying “operations” as “drilling operations” enables the landowner to police the land and determine that as long as there is “actual drilling of the well, with a rig capable of drilling to permitted depth,” progression into the secondary term should be granted. See, McFarland’s Checklist. In Kansas, anything less than actual drilling however is risky. See, Herl v. Legleiter, (Kan. Ct. App. 1983). However, Exhibit A does not clarify, amongst other situations, whether an existing well that has ceased to produce oil and gas would be included. Additional difficulties arise for larger landowners when oil companies maintain the “operations” of only one well, even if the lease is comprised of thousands of acres of land. It seems therefore that landowners need to pay attention to the fine print and argue in favor of clarifying habendum production provisions before signing a lease. Such a clarification would be clearer for both parties and could avoid litigation. What rights are granted to the lessee in an Oil and Gas Lease? Under the Granting Clause, the landowner grants the oil company the right to explore, develop and produce certain substances from the leased premises and to use the surface of the land to support such operations. See, Rethinking the Oil and Gas Lease and Hunt Oil. Difficulties arise for the landowner therefore when surface activities are not defined within the lease, leading to unwanted structures being built on the leased surface, sub-surface and other areas that fall within a “Mother Hubbard” clause. A “Mother Hubbard” clause encompasses land that is owned by the landowner, but not covered under the lease description. Additionally, many “Producers 88” fail to define what substance interests are being granted (if any) in addition to the oil and gas, or what type of gas is being granted. See, YouTube: Tips for Landowners at 25.20 minutes. Generally speaking, the “Producers 88” tends to include a “very broad statement of rights” to enable oil companies to use the leased surface, working alongside an implied easement to use the surface reasonably. See, 6 West's Tex. Forms, Minerals, Oil & Gas § 3:2 (4th ed.,) (available on Westlaw.) Such “reasonable” surface use developed from Texas, whose accommodation doctrine specifies that if the oil company substantially impairs the existing use of the surface by the landowner, the oil company must use other alternatives if reasonably available. See, Sup. Ct in Getty Oil Co. v. Jones (1971). Many commentators therefore agree that landowners should “clearly define” what oil companies can do on the surface of the land, in accordance with the substances granted. Additionally, landowners should “impose specific restrictions” on oil companies, such as the location of wells and equipment, the storage and removal of supplies, the use of water and advanced notice of any proposed activities. See, Modern Oil and Gas Lease. If the oil company breaches such restrictions laid down, damages equal to the fair market value of the used land or actual value of the damaged personal property should be paid to the landowner. See, Contracts as Fences. If the lease is not adapted in the landowners’ favor, landowners may be at risk of courts ruling in favor of oil companies’ “reasonable use” of the land surface. With regards to the substances being leased to oil companies, advice to landowners is more problematic. Leases may grant “oil and gas” interests or “oil, gas and other mineral” interests. One of the interpretive issues of late stems from whether methane gas, found in the coal seams, is classified as “gas” within the leased term “oil and gas.” Such an issue is highlighted within the “Producers 88” in Exhibit A, Subsection 1. Courts have frequently looked to the intent of both the landowner and the oil company in assessing such an issue. However, one major drawback to this approach is that the parties usually have no intent concerning “methane gas” until it is extracted. Courts then choose to consider “extrinsic information,” which causes uncertainty in landowners’ ownership rights generally and “supplants” the lease with a subjective judgment. See, Modern Oil and Gas Lease. However, Texas has managed to limit the types of minerals that oil companies can extract when the landowner fails to define “oil, gas and other minerals” in the lease. See, Moser v. U.S. Steel Corp, Sup. Ct. of Texas, (1984.) Generally, a mineral: “includes every inorganic substance that can be extracted from the earth...whether it is solid, as rock, fire clay, the various metals and coal, or fluid as mineral waters.” See, Contracts and Issues for Landowners. However, in the Marcellus shale region, which spans Pennsylvania, New York and Ohio, landowners who have not been afforded such “Texan protection” need to be careful when including “other minerals” in their lease. This is because landowners’ future rights to the Utica Shale, which lies at greater depths to the Marcellus, are at risk of being subsumed into their Marcellus lease with oil companies. See, Common Issues. As such, landowners need to be careful to exclude such substances, or a conveyance of that right might be implied by the landowners’ failure to define it. See, Anderson v. Mayberry, App. Ct, Oklahoma (1983). A more straightforward method for landowners would be to therefore expressly define the granted mineral rights in the lease and avoid confusion by excluding any mention of “other minerals.” How is the landowner paid in the Oil and Gas Lease? As mentioned previously, the landowner is paid through initial bonus, delay rentals and royalty payments. Clearly, the landowner wants to gain the highest return possible. McFarland however emphasizes that a “good deal” for the landowner is dependant on: Whether there is already production in the area (bonus and royalties are likely to be higher if so, as the oil company has already paid for initial start up costs and established production lines.) Whether numerous companies are competing in the area (competition will raise the price.) The price of the prevailing market rate in the area (which is mainly assumed through geological location.) The amount of mineral acres the oil company is leasing from the landowner. Utilizing such information in initial negotiations with oil companies is vital if landowners want to be awarded higher payments. See, McFarland’s Checklist. Bonus: The option to explore and develop potential oil, gas and/or other mineral reserves for a primary term is acquired through an up-front payment (a “signing bonus.”) See, Rethinking the Oil and Gas Lease. The signing bonus is based on the number of “net mineral acres,” which is the number of leased acres times by the interest in the minerals. As such, the more acres the landowner leases, the higher the signing bonus will be. Rental Delays: The purpose of Rental Delay payments is “to make the lessee take a look at his “whole card” to determine if he is serious in developing the lease.” See, Bernard E. Nordling, Landowners' Viewpoints in Pipeline Right-of-Way and Oil and Gas Lease Negotiations, J. Kan. B. Ass'n, Spring 1983, (available on Westlaw.) Under an “unless” delay rental clause, lease termination occurs automatically at the end of an annual period in the primary term if drilling operations and production have not begun, “unless” a delay rental is paid. See, 6 West's Tex. Forms, Minerals, Oil & Gas § 3:2 (4th ed.,) (available on Westlaw.) In determining whether delay rental payments are due, reference back to the “Granting Clause” is necessary to emphasize the problems encountered under the definition of “production.” Today however, it is more common to see “paid-up” leases. See, YouTube: Tips for Landowners at 21 minutes. This means that the oil company will have paid in advance all of the rentals that might have become due under the “Signing Bonus,” if production is later delayed. As such, the lease will not terminate during the primary term and no further payments are due until actual production commences and royalties emerge under the secondary term. See, 6 West's Tex. Forms, Minerals, Oil & Gas § 3:2 (4th ed.,) (available on Westlaw.) Royalties: The Royalty Clause is the most important aspect to the oil and gas lease for the landowner, but it is also the most heavily litigated. The “deceptively simple” clause seeks to compensate the landowner for their share of the extracted oil, gas and/or other minerals from their land, once production (and sometimes refinery) has commenced. See, Modern Oil and Gas Lease. As highlighted in the “Granting Clause,” landowners need to specify what substances are being granted in the Royalty Clause. If the clause is silent, the courts could rule in favor of the oil company and withhold any royalties due to the landowner. See, 6 West's Tex. Forms, Minerals, Oil & Gas § 3:2 (4th ed.,) (available on Westlaw.) The Royalty Clause therefore should underscore what substances the landowner will be paid for and how the landowner will be paid. Typically, landowners are paid as a fraction or percentage of the production of oil and gas from their land. In the past, “Producers 88” would set aside a royalty of 1/8 to the landowner. Today, depending on the bargaining position set out above, landowners can negotiate up to 1/4. See, McFarland’s Checklist. Also, see YouTube: Tips for Landowners at 11 minutes. Due to the “physical and economic differences” of oil and gas, alternative methods of payment are used in Royalty Clauses, depending on which substance(s) are being granted. Landowners granting rights to oil are paid a royalty in kind upon production. See, Wilson v. United Texas Transmission (Tex. App. Corpus Christi 1990). Where royalty is due in kind or where there is an arm's length sale at the well, there are few arguments. Gas is more complicated. The general rule is that the more gas an oil company is able to sell, the better “market price” or “market value” it can obtain for both the company and the landowner (especially in more recent times of “gas surplus.”) Gas’ royalty is therefore paid as a percentage of the “proceeds” made through an oil company’s business activities after production. This stems from the fact that post-production costs are limited if processing gas in bulk. Gas also has to be sold in alignment with the amount being produced, as it is generally not practicable to store natural gas at the well. See, 6 West's Tex. Forms, Minerals, Oil & Gas § 3:2 (4th ed.,) (available on Westlaw.) However, approaches of this kind carry with them various well-known limitations. Firstly, if the landowner gains a percentage of the gas proceeds made through the oil companies “business activities,” what part of the “business activity” proceeds is the landowner entitled to? If the landowner wants to be involved in all of the business activity of the gas (from wellhead to final sale,) the landowner will have to suffer the costs associated with various post-production “business activities,” like gas separation, processing and marketing, before the royalty is allocated. The landowner’s choice of involvement is made even more difficult in ascertaining where “downstream” the oil company will sell the gas. Will it happen at a distant pipeline delivery point after separation, or at a market hub after processing? Ultimately, the costly post-production procedures will increase the end value of the gas to the landowner’s advantage. See, Modern Oil and Gas Lease. Such a rule is known as the “Capture and Hold.” Many courts have “unanimously accepted” that because landowners’ royalty is free from the cost of initial production, any subsequent post-production costs that the landowner wants to be involved in will not be deducted from their final royalty payment. As such, if the landowner wants to be involved in the post-production activities for a larger end profit, the gathering, processing and marketing costs will have to be accepted. See, 6 West's Tex. Forms, Minerals, Oil & Gas § 3:2 (4th ed.,) (available on Westlaw.) It is advised therefore that the landowner should negotiate to be involved in all of the post-production “business activities” of gas and leave it up to the commercial pragmatism of the oil company to ascertain where to sell the gas at its best price. However, there may be some support for landowners under the “marketable product” rule that has recently been enforced by courts. The rule assumes that there is an implied covenant on behalf of the oil company to market the product, indicating that landowners should only be involved with the gathering and processing costs. However, this method of analysis is bad policy and may cause wells to be abandoned. See, 6 West's Tex. Forms, Minerals, Oil & Gas § 3:2 (4th ed.,) (available on Westlaw.) As such, all post-production activities that the landowner wants to be involved in and which costs money (with the guidance of the oil company,) should be specifically referred to in the Royalty Clause (see Exhibit A, Subsection 3.) It would then be “improper” for the court to imply the marketable rule covenant if all avenues are expressly stated. See, Oil and Gas Law in a Nutshell (Paperback.) Can an oil company assign the Oil and Gas Lease to a third party? Aside from the harmful effects of the three major clauses analyzed above, landowners most commonly find themselves suffering from the unexpected results of an Assignment Clause within an oil and gas lease. An Assignment Clause is customarily included within the majority of “Producers 88” leases, regardless of whether the lessee has an intention to assign or not. See, Rethinking the Oil and Gas Lease. It ultimately enables the lessee to assign the rights granted to them to another entity of their choice. A key problem with this is that particularly when the demand for oil and gas is high, entrepreneurial bodies rush to assign previously held lease rights to the highest bidder and/ or investors, regardless of standing. Landowners are therefore left surprised to find unanticipated third parties on their land, attempting to produce oil and gas, without their knowledge or consent. See, McFarland’s Checklist. Perhaps the most serious disadvantage for the landowner is the fact that once the lessee has assigned their rights elsewhere, the lessee is no longer liable for any obligations that arise under the lease after the date of assignment, including unpaid royalties. See, McFarland’s Checklist. As such, the recommendation for landowners is to clarify that the Assignment Clause will not permit any assignment without the landowner’s prior written consent. If written consent is not obtained from the landowner, any future assignment should be held void ab initio by courts. Written consent would enable landowners to research the potential assignee’s business model and past record before allowing them to develop their land. See, Contracts as Fences. However, it may be difficult to encourage the lessee to agree to such a provision, as standard assignability clauses are “an important attribute” to any oil and gas lease for the lessee. An alternative for the lessee therefore (that works in the landowner’s favor) would be to agree to a standard Assignment Clause, but stipulate that the lessee would remain liable for all obligations and liabilities under the lease if rights were assigned. This would encourage the lessee to assign the rights to a “financially responsible” company. See, Contracts as Fences. Alternatively, another option would be to again, enforce the Assignment Clause, but gain written confirmation that the lessee will retain a majority holding in the rights being assigned. This would maintain previous practices and again limit the effect of any outstanding liabilities. Both options achieve equity on behalf of the parties and inspire confidence in the landowner when signing an oil and gas lease. Ultimately, whichever method is implemented, the landowner must remember to gain copies of the assignments in order to keep track of the interests in his land. See, McFarland’s Checklist. Is it time for the traditional Oil and Gas Lease to be reformed in the landowners’ favor? Many commentators argue that despite countless years of adverse judicial rulings, the “Producers 88” has remained largely unchanged with regards to landowners’ rights. If the traditional oil and gas lease is not the optimal relationship for both parties, why has it endured? After reading scores of literature, it seems as if the blame for its endurance lies squarely on the courts. Pierce talks of the willingness of the courts to creatively interpret oil and gas leases with “new phrases, clauses, sentences or sections” instead of choosing to confront the Leases’ conscionability as a whole. As such, the traditional “Producers 88” has been preserved when otherwise it would have “fallen into disuse.” Despite the argument that the “new phrases” added by the courts were an attempt to protect the landowner, it was ultimately counterproductive. Adding to the “Producers 88” recognized the basis of the form as legitimate, making any type of reform unlikely when set against the thousands of court decisions in its favor. See, Rethinking the Oil and Gas Lease. However, such explanations tend to overlook the fact that oil companies are also to blame. Lease additions made by the courts enabled oil companies to choose to “revise only the portions of the lease necessary to respond to the court” whilst later expressly excluding their application, as seen through implied covenants. Oil companies have therefore worked alongside the judiciary in choosing not to “reinvent the wheel” with regards to the “Producers 88.” Instead, oil companies continue to use the traditional form without much care as to why such clauses are used or how it affects the landowner. See, Rethinking the Oil and Gas Lease. However, there are limitations as to how far the blame on the judiciary and the oil companies can be taken. The landowners are ironically also to blame for their own position under the traditional oil and gas lease today. Minor landowners in particular have had a natural tendency to “embrace” any lease form in exchange for instant monetary gain. See, Rethinking the Oil and Gas Lease. Also, see YouTube: Tips for Landowners at 10.30 minutes. This is done without awareness of the effect on their future rights or adding to the general deterioration of landowner negotiating power against the growing might of the “Producers 88.” Practitioners should therefore focus on increasing landowner awareness and furthering the efforts of this “Q & A” by improving the landowner’s weaker bargaining position. In conclusion, it is unlikely therefore that the traditional oil and gas lease will be reformed any time soon. If anything, it “is probably here to stay” until courts leave the industry to experiment alone. See, Modern Oil and Gas Lease. In the meantime however, there are a number of important points highlighted above in the “Producers 88” that the landowner should be made aware of, to improve their position. In particular, restrictions or additions to the nature of landowners’ rights need to be specifically referred to and incorporated within the lease in future. Any oil company acting in good faith should, in theory, accept such amendments if sufficient amounts of minerals are at stake. For the smaller landowner however, negotiations might prove more challenging.