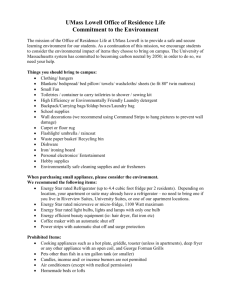

Innovative Enterprise William Lazonick National University of Ireland Galway March 5, 2009

advertisement

Innovative Enterprise William Lazonick Center for Industrial Competitiveness University of Massachusetts Lowell National University of Ireland Galway March 5, 2009 Innovative enterprise and economic performance • Employees: Higher pay, better work conditions • Creditors: More secure paper • Shareholders: Higher dividends or share prices • Government: Higher taxes • The Firm: Stronger balance sheet AND • Consumers: Higher quality, lower cost products Lazonick: UMass Lowell By creating new sources of value (embodied in higher quality, lower cost products), the innovative enterprise makes it possible (but by no means inevitable) that, simultaneously, all participants in the economy can gain: Theories of resource allocation Economics is about modes of resource allocation that generate superior economic performance (that is, “economic development”) Social characteristics of a mode of resource allocation: who makes allocation decisions?, what kind of investments do they make? how are the returns from those investments distributed? The theory of the market economy: the conventional perspective -- most critiques focus on state intervention to correct for market imperfections and market failures My argument: a viable economic theory needs to focus on the roles of business enterprise and innovation in the resource allocation process -- then bring in the role of the (developmental) state Lazonick: UMass Lowell Think organizations, not markets Market imperfections? (economic processes) Assumes that “perfect markets” are an ideal mode of economic organization – but market coordination does not generate innovation, which entails a social process that is uncertain, collective, and cumulative process STOP THINKING “PERFECT MARKETS”, START THINKING “INNOVATIVE ORGANIZATIONS” Market failures? (economic outcomes) Assumes an expectation that the market can generate desirable economic outcomes – but undesirable outcomes – e.g., an inequitable distribution of income – may reflect ORGANIZATIONAL FAILURES Lazonick: UMass Lowell Economic approaches to Innovation and Theories of the Firm Economic Institutions National Innovation Systems Competitive Advantage of Nations Sources of Industrial Leadership Social Conditions of Innovative Enterprise Theory of the Innovative Enterprise Industrial Sectors Business Enterprises Five Forces Competitive Advantage Transaction-Cost Theory Resource-Based Theory Agency Theory Disruptive Technology Game Theory Econ. of Industrial Innovation Knowledge Creation Theory of the Growth of the Firm Evolutionary Theory Dynamic Capabilities Lazonick: UMass Lowell The key questions What is the relation of various approaches to innovation and theories of the firm to the “social conditions of innovative enterprise”? I ask: What do each of these approaches have to say about innovative strategy, organizational learning, and investment finance? and b) what are the implications for understanding the performance of the enterprise of introducing the concepts of strategic control, organizational integration, and financial commitment – which I will develop in this talk -- into the analysis? Lazonick: UMass Lowell What is a “firm” and what does it do? “the firm”: transforms productive resources into goods and services that can be sold to generate revenues To transform productive resources into goods and services, a firm engages in three generic activities: • strategy: allocates resources to investments in human and physical resources (who?) • organization: develops the productive capabilities of these resources (what?) • finance: seeks to generate returns on the resources that it has developed through sale of goods and services (how?) Lazonick: UMass Lowell What is an innovating firm? Definition of “the innovating firm”: given prevailing factor prices, the innovating firm transforms the productive resources under its control into higher quality, lower cost goods and services than had previously been available at prevailing factor prices • thus defined, the innovating firm is an outcome of a process that is a) uncertain (cannot be done optimally) b) collective (cannot be done alone) c) cumulative (cannot be done all at once) Lazonick: UMass Lowell Theory and history Lazonick: UMass Lowell The theoretical challenge: What are the characteristics of the business enterprise that enable strategy to confront uncertainty, organization to mobilize the collective process, and finance to sustain the cumulative process that can result in innovation? The historical challenge: Constructing relevant theory from the comparativehistorical analysis of the role of innovative enterprise in the economic development of regions and nations Integration of theory and history: At any point, theory serves as both a distillation of what we know and a guide to discovering what we need to know “Catching up with history” • As economists, we want to be able to analyze “history” as it unfolds around us • We need to understand the social processes that govern economic change • We can only understand economic change by analyzing the process as it has already occurred in different times and places, i.e., a comparativehistorical approach • But we do not want to be stuck in the historical past • We want to “catch up with history” Lazonick: UMass Lowell Back to basics Starting point for constructing a theory of innovative enterprise: textbook theory of the optimizing -- or “uninnovative” -- firm: Why un-innovative? a) “Strategy”: all firms in an industry incur same fixed costs of entry, given by exogenous industrial conditions (technology and markets) b) “Organization”: firm does not develop technology, markets instantly absorb all that the firm wants to produce -- but problem with addition of variable factors c) “Finance”: implicitly assumes fixed costs can be funded through capital markets – if product prices do not cover variable costs, some firms quit the industry Lazonick: UMass Lowell Textbook theory of the optimizing firm Lazonick: UMass Lowell price, cost average cost marginal cost p c marginal and average revenue q c output Why is the cost curve U-shaped?: with expansion of output, “control loss” of adding more variable inputs results in lower average productivity of variable inputs, which at some point offsets higher average productivity of fixed inputs through economies of scale Is there an alternative to this theory of the firm? Technological and market conditions given by cost and revenue functions. The “good manager” optimizes subject to technological and market constraints. Transforming the theory of the optimizing firm into a theory of the innovating firm… Strategy: innovating firm makes high-fixed-cost investments that differentiate it from other firms Lazonick: UMass Lowell From high fixed costs to low unit costs Organization: a) innovating firm must develop the capabilities of its investments, creating a problem of high fixed costs; b) rise in unit costs resulting from “control loss” NOT final outcome, but challenge to learn solutions Finance: source of finance matters because returns are uncertain : it takes time to develop productive resources and gain access to markets – need “patient capital” so that the firm does not have to drop out of the industry when unit cost exceeds product price Comparing optimizing and innovating firms p = price; q = output; c = perfect competitor pmin = minimum breakeven price; qmax = maximum breakeven output price, cost How does the innovating firm transform high fixed costs into low unit costs? average cost marginal cost p Lazonick: UMass Lowell c innovating firm marginal and average pmin revenue c q c output optimizing firm qmax c output Technological and market conditions are given by cost and revenue functions. The “good manager” optimizes subject to technological and market constraints. Through strategy, organization, & finance, innovating firm transforms technologies and markets to generate higher quality, lower cost products. There is no “optimal” output or “optimal” price. Shaping the innovative cost curve Lazonick: UMass Lowell price, cost actual increasing costs innovating firm innovating firm: phase 1 optimizing firm expected decreasing costs output Through innovative strategy , IE expects to outcompete OF. But, in period one, IE’s strategy only results in high unit costs, and IE remains at a competitive disadvantage. innovating firm:phase 2 output By internalizing variable factor creating increasing costs, IE incurs even higher fixed costs but the investment enables it to “unbend” the U-shaped cost curve. price, cost Invest more, t1, to overcome increasing costs actual increasing costs, AC1 innovating firm, t1: ACinnovator, p1 high fixed costs + increasing variable costs = competitive disadvantage MCoptimizer pc ACoptimizer MR Innovative investment strategy, t0: “expected” decreasing costs optimizing firm: in textbook fashion, equates MR and MC to maximize profits innovating firm, t2 even higher fixed costs become lower unit costs = competitive advantage How, over time, can innovation outcompete optimization? ACinnovator,AC2 qc Lazonick: UMass Lowell output Strategy, organization and finance in the theory of the innovating firm price, cost innovating firm: phase 1 Innovative strategy uncertain: continued strategy, organization, & finance needed to get the enterprise past phase one; remains at a competitive disadvantage Innovative strategy tends to be high-fixed cost; need to develop interrelated set of capabilities; extent of fixed costs depends on size of investments and duration of time between investments and returns Innovative strategy only results in low units costs if products can be sold; otherwise they will not be produced: need to bring product market demand into the analysis optimizing firm innovating firm:phase 2 output Lazonick: UMass Lowell Accessing market segments: product innovation Lazonick: UMass Lowell price, cost high income, price insensitive Pr od uc middle income, price matters Supply curve t1 Phase 1: IF accesses high- income segment ti nn ov at io low income, price sensitive Supply curve t2 n Phases 2 and 3: IF accesses lower income segments Demand segments output (units of quality) What is the source of high income demand? For example: integrated circuits - military; jet engines - military; calculators - engineers; orphan drugs – national healthcare system Accessing market segments: process innovation Lazonick: UMass Lowell price, cost high income, price insensitive s es oc Pr Phases 2 and 3: IF access higher income segments middle income, price matters in tio va no low income, price sensitive n Supply curve t2 Phase 1: IF accesses lowincome segment Demand segments Supply curve t1 output (units of quality) Key to the indigenous innovation strategies of developing countries: e.g., Japan from 1950s, Korea from 1980s, China from 1990s Interdependent dynamics of supply and demand The Innovating Firm promises to share the gains of innovative enterprise with employees to retain and motivate them. When innovation succeeds, “shared gains” are rewards for unbending the cost curve (c1 to c2) and increasing the extent of the market (d1 to d2). price, cost c1 p 1 d2 d1 2 Profits c2 “shared gains” ch = hypothetical cost structure with wages unchanged from c1 q1 q2 output For innovating firm, transformation of cost curve can reshape its demand curve • “shared gains” with employees are integral to this productive transformation • price-setting is integral to its competitive strategy Lazonick: UMass Lowell p What do entrepreneurs do? • Entrepreneurial strategy: innovation is inherently uncertain • Technological uncertainty • Market uncertainty • Competitive uncertainty • It matters who the entrepreneurs are – what types of people are able and willing to allocate resources to innovative investment strategies? • Overcoming uncertainty to generate innovation requires finance and organization • Why finance? You cannot do everything at once • Why organization? You cannot do everything alone Lazonick: UMass Lowell Entrepreneurship and innovation • That is, innovation is a cumulative and collective process that confronts uncertainty • Entrepreneurship is the allocation of resources to an innovative investment strategy within a distinct unit of strategic control, i.e., a firm • The need for finance means that entrepreneurs may have to share strategic control with financiers • The need for organization means that entrepreneurs may have to share strategic control with managers • The entrepreneur initiates the innovation process, but the more cumulative and collective that process, the more likely that the role of “entrepreneurship” will disappear Lazonick: UMass Lowell Industries matter Industries differ in terms of technological, market, and competitive conditions – implications for developing and utilizing productive resources • technological conditions affect the requirements for collective and cumulative learning – i.e., developing productive resources • market conditions affect the possibilities for transforming high fixed costs into low units costs – i.e., utilizing productive resources • competitive conditions determine the extent to which a firm must develop and utilize productive resources in order to be an innovative enterprise Lazonick: UMass Lowell Social conditions of innovative enterprise Under what conditions do strategy, organization, and finance result in innovation? Conceptualize the firm as a social organization characterized by a set of “social conditions” that influence the way that strategy, organization, and finance are done Why “social”? Strategy, organization, and finance reflect relations among people in the economy who occupy different hierarchical and functional positions and have different abilities and incentives Why focus on “the firm” as a social organization? 1) In the modern economy, the firm is the critical unit of control over the allocation of resources to innovative strategies. 2) The modern firm employs lots of people (50 is a small enterprise and 100,000 is not unusual), many of whom interact in collective and cumulative learning processes that are central to innovation. 3) The modern firm cannot exist without substantial and sustained funding; innovative strategy and organizational learning increase the need for investment finance. Lazonick: UMass Lowell Strategy in the innovative enterprise Strategic resource allocation confronts uncertainty: Technological: Can the firm develop superior processes and products? Market: Can the firm secure a large enough extent of the market? Competitive: Will rivals generate higher quality/lower cost products? Social Condition of Innovative Enterprise No. 1: Who makes innovative strategy? ¾ abilities and incentives of those who exercise strategic control in the firm Lazonick: UMass Lowell Organization in the innovative enterprise Innovation requires organizational learning: Collective learning: learning depends on the interaction of people organized in a hierarchical and functional division of labor Cumulative learning: what can be learned today depends on what was learned yesterday Social Condition of Innovative Enterprise No. 2: What innovative investments do they make? ¾ organizational integration of skill bases that can generate collective and cumulative learning Lazonick: UMass Lowell Finance in the innovative enterprise Transforming high fixed costs into low unit costs Fixed costs: determined by size & duration of technological transformation Unit costs: depend on extent & timing of market access Control over revenues: keep innovative organization intact while investing in the growth of the firm Social Condition of Innovative Enterprise No. 3: How are returns from investments distributed? ¾ sources of financial commitment that sustain technological transformation and market access Lazonick: UMass Lowell Social conditions of innovative enterprise • Strategic control: a set of relations that gives decisionmakers the power to allocate the firm’s resources to confront uncertainty by transforming technologies and markets to generate higher quality, lower cost products • Organizational integration: a set of relations that create incentives for people to apply their skills and efforts to engage in collective learning • Financial commitment: a set of relations that secure the allocation of money to sustain the cumulative innovation process until it generates financial returns Lazonick: UMass Lowell Strategic control KEY QUESTIONS: • Strategic control and asset ownership: How does strategic control change with the growth of the firm? Why might asset ownership be separated from managerial control? Who is included in the structure of strategic control? • Strategic control, abilities: Who is able to allocate resources to innovative investment strategies? What role does experience in the firm and industry play? • Strategic control, incentives: Do they want to allocate resources to innovation? Why not just reap the returns of past investments? How do their individual incentives affect “organizational” goals? Lazonick: UMass Lowell Organizational integration KEY QUESTIONS: • Innovative skill bases, abilities: What hierarchical responsibilities and functional specialties does the firm seek to integrate into organizational learning processes? What types of employees are “key”? • Innovative skill bases, incentives: How does the firm recruit/retain and motivate its “key” employees? How does the structure of incentives reconcile individual behavior with organizational goals? • Innovative skill bases, change: What happens when competitive challenges render innovative skill bases obsolete ? How are collective/cumulative learning trajectories transformed? Lazonick: UMass Lowell Financial commitment KEY QUESTIONS: • Internal funds: Are internal sources of funds important for financing innovation? How does the firm ensure that it can retain control over its revenues? • Debt and the finance of innovation: Do bank loans provide a source of financial commitment? In what relation to internal funds? Do bond issues provide financial commitment? Why loans or bonds? • Equity and the finance of innovation: Does private equity provide financial commitment, and to what types of companies? What is the role of the stock market in the finance of innovation? Lazonick: UMass Lowell Strategy and organization within the firm Lazonick: UMass Lowell Strategy and Learning Innovative Skill Bases Who allocates resources? Are they integrated with learning processes? Functional Technical Specialists Skilled “Semi” Skilled Unskilled Production Workers Hierarchical Integration? Middle Broad skill base: functional integration How broad and deep are the skill bases that the learning process requires? Top Executives Managers Deep skill base: hierarchical integration Integration? Technical Specialists Office Workers Skilled “Semi” Skilled Unskilled Research agenda: how do innovative skill bases vary in breadth and depth across nations, industries, and enterprises at a point in and over time? Strategy and organization within and across units of strategic control Unit of Strategic Control Inter-Company Relation Proprietary Firm Industrial District New Venture Vertical Going Concern Corporate Enterprise Divisions Conglomerate Interactions? Spinoffs Mergers and Acquisitions Buyouts Enterprise Group Horizontal Subcontractor Joint Venture Strategic Alliance Research Consortium • Evolution of strategic control within a company? Impact on learning? • Structure of strategic control across companies? Impact on strategy? • Organizational integration across companies? Impact on learning? • How do the sources of finance affect the structure of strategic control? Lazonick: UMass Lowell Evolution of Company Structure Cross-Company Structure of Control and Integration? National institutions and business organizations in the innovation process Governance institutions and strategic control: What are the rights and responsibilities that govern the allocation of productive resources (labor and capital) in the economy? Where in the economy is control over allocation decisions located? What are the social processes that monitor, sanction, and reform such control? Employment institutions and organizational integration: To whom does society provide education, training, and access to research? Through what organizations? For what purposes? Who pays? How do people get jobs? With what expectations of rewards over what time frame? Are careers within or across firms? Investment institutions and financial commitment: How are financial resources mobilized in the economy for investments in productive resources? From what sources? On what terms? With what expected returns? Lazonick: UMass Lowell Social conditions of innovative enterprise Social Conditions of Innovative Enterprise Economic Institutions Governance Employment Investment reform enable and proscribe Strategic Control Organizational Integration Financial Commitment embed Industrial Sectors Markets Technologies constrain shape Business Enterprises Organization Strategy transform Finance Competition challenge Lazonick: UMass Lowell Social institutions and innovative enterprise Do governance, employment, and investment institutions enable or proscribe innovative enterprise?: • Need to understand the evolving relation between social institutions and organizations in specific contexts Do institutions that support innovative enterprise in one era constrain it in another? • Need to understand how, when, and whether, industrial and organizational change drives institutional change A research agenda: • Comparative-historical study of capitalist development with a view toward constructing a theory of innovative enterprise that explores (not ignores) historical experience Lazonick: UMass Lowell Varieties of capitalism in comparative-historical perspective Marshallian industrial districts: craft foundations made Britain “workshop of the world” in late 19th century US managerial corporation: integrated management structures made US dominant in first half of 20th century Japanese challenge: power of broad and deep skill bases US New Economy: power of highly educated skill bases The rise of China and India: globalization of the labor force Lazonick: UMass Lowell European alternatives in second half of 20th century France: functional integration for complex systems Germany: hierarchical integration for high-quality goods Italy: emergence of “neo-Marshallian” industrial districts UK: organizational segmentation, not a viable alternative Marshallian industrial districts Strategic control: • proprietary control (even with public shareholding (e.g., Oldham limiteds) by owner/managers with highly specialized capabilities (restriction on firm growth) Organizational integration: • piece-rate payments; worker-run, on-the-job training for highly specialized occupations; minimum of formal education (learning regions, making entry easy) Financial commitment: • limited retentions (pressure for dividends when available); living off invested capital; cyclical collective bargaining (all of which constrained firm growth) UK: 20th century legacy of Marshallian districts Strategic control: • persistence of proprietary control across British industry; relative underdevelopment of managerial organization; stock markets run for shareholders Financial commitment: • problem of shareholders who demand payouts rather than leave funds in the firm to finance growth Lazonick: UMass Lowell Organizational integration: • control over work organization left with workers, even in new industries (autos, electronics) in which, until 1960s, unions not a force; administrative & technical specialists segmented from top management decision-making Italian industrial districts Lazonick: UMass Lowell Strategic control: • flexible specialization because of proprietary control Organizational integration: • vertically specialized and horizontally fragmented structure of industrial organization: an alternative to mass production Financial commitment: • role of regional financial institutions Similar industries to British IDs: but they declined from interwar period, and roots of decline much earlier What makes Italian industrial districts different from British (the original Marshallian) industrial districts? Sustainability of Italian industrial districts? Strategic control: • far more entrepreneurship than British IDs; far more collective services (training, administration, finance, marketing), more diversified set of industries Organizational integration: • not necessarily sustainable in the face of innovative competitors -- example of the Italian upholstered furniture industries of Emilia-Romagna and MateraAltamura-Santeremo Financial commitment: • internal finance and the growth of the firm -- will sufficient commitment be maintained to the funding of collective services? Lazonick: UMass Lowell The “Marshallian” industrial district Horizontal competition O r V g e a r n t i i z c a a t l i o n ... ... ... ... ... sales Global markets design assembly components Local resources Skilled labor Finance Infrastructure machines Collective services? Lazonick: UMass Lowell Emergence of lead firms? Horizontal competition O V r e g r a t n i i c z a a l t i o n sales Global markets design assembly ... ... components Local resources Skilled labor Finance Infrastructure machines Global labor? Collective services? Lazonick: UMass Lowell Legacy of the Marshallian industrial districts Strategic control: • persistence of proprietary control across British industry; relative underdevelopment of managerial organization; stock markets run for shareholders! Organizational integration: • control over work organization left with workers, even in new industries (autos, electronics) in which, until 1960s, unions not a force; administrative & technical specialists segmented from top management decision-making Financial commitment: • problem of shareholders who demand payouts rather than leave funds in the firm Lazonick: UMass Lowell The US Old Economy business model Strategic control: • separation of ownership and control secured by the rise of liquid stock markets and widespread distribution of shareholding; precondition for managerial control Organizational integration: • career rewards: distinction between salaried managers and “hourly” workers; hierarchical specialization & hierarchical segmentation; national educational system important for managers, especially higher education Financial commitment: • retentions (after stable dividends), bonded debt, stock issues relatively unimportant Lazonick: UMass Lowell US managerial control confronts UK craft control Lazonick: UMass Lowell United States Executives =Hierarchical Integration Specialists XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX “Semi-skilled” workers =Functional Segmentation Britain Executives XXXXXXXXXX Specialists Craft Workers and Assistants XXX =Hierarchical Segmentation The Japanese challenge Strategic control: • secured by cross-shareholding; career managers exercise control; the post-war rise of the “third-rank” executive Organizational integration: • lifetime employment: career rewards for all salaried personnel, blue collar and white collar; hierarchical and functional integration, notwithstanding hierarchical and functional specialization (i.e., interactive learning); high level of general education with in-house training Financial commitment: • main-bank system: retentions (with low dividends) highly leveraged by state-supported bank finance Lazonick: UMass Lowell Organizational integration and international competition United States and Japan, circa 1980 United States =Hierarchical Integration = Hierarchical Interaction Executives ? ? Specialists ? ? XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX “Hourly” Operatives =Functional Segmentation Japan Lazonick: UMass Lowell Executives Specialists XXX =Hierarchical Segmentation Regular Male Operatives XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Females/Temporary Employees German and Japanese business models compared =Hierarchical Germany Integration = Hierarchical Interaction Executives Specialists Craft Workers Executives Specialists XXX = Hierarchical Segmentation Regular Male Operatives XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Most females and temporary employees Lazonick: UMass Lowell Japan = Functional Segmentation The French business model France PDG XXXXXXXXX Cadres XXX =Hierarchical Segmentation X X X X X X X X Techniciens XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Ouvriers Lazonick: UMass Lowell Product quality Product cost High quality Low cost High cost Japan Germany Italy France Low quality United States (OE) Britain Adaptation and globalization in 1990s and 2000s Lazonick: UMass Lowell Institutions and international competition: 1980s The rise of the New Economy business model Lazonick: UMass Lowell Strategic control: • control by managers secured by liquid capital markets; may be owners but all strategic managers highly specialized & experienced in particular industrial sector Organizational integration: • all salaried (not hourly), career rewards for motivation plus stock-based compensation as recruitment/retention tool; tap into global labor forces as highly educated labor flows to capital, and capital flows to less educated labor Financial commitment: • venture capital reallocates money and people, funds raised in IPO, retentions, little if any dividends and debt Business model, old and new OEBM NEBM Strategy, product growth by building on internal capabilities; expansion into new product markets based on related technologies; geographic expansion to access national product markets new firm entry into specialized markets; sell branded components to system integrators; ac-cumulate new capabilities by acquiring young technology firms Strategy, process development and patenting of proprietary technologies; vertical integration of the value chain, at home and abroad cross-license technology based on industry standards; vertical specialization of value chain; outsourcing/offshoring routine work Finance venture finance from personal savings, family, and business associates; NYSE listing; pay steady dividends; growth finance from retentions leveraged with bond issues organized venture capital; IPO on NASDAQ; low or no dividends; finance from retentions plus stock as an acquisition currency; stock repurchases to support stock price Organization secure employment: “organization man” (career with one company); industrial unions; DB pension; employer-funded medical insurance in employment and retirement insecure employment: interfirm mobility of labor; broad-based stock options; non-union; DC pension; employee bears greater burden of medical insurance Lazonick: UMass Lowell The US New Economy business model US-Based Operations Global Operations Executives O V r e g r a t n i i c z a a l t i o n Global markets sales OEM design Specialists Global labor Contract manufacturers Component producers Global labor Machinery makers Venture capital Lazonick: UMass Lowell Business enterprise and economic development • Economic development: not just “states” and “markets” • Role of states: invest in uncertain technologies, access global markets for national firms, limit competition in domestic markets, subsidize innovative enterprise • State interventions to support innovative enterprise cannot be construed as “market failures” • Power of firms to control the flow or capital and labor, and to have privileged access to product markets cannot be construed as “market imperfections” • Need a theory of innovative enterprise that can comprehend cross-national institutional conditions to explain international competition advantage Lazonick: UMass Lowell Why has neoclassical economics ignored the analysis of innovative enterprise? • Illusion that of a world of “perfect” markets as yielding “optimal” economic performance, and hence the analytical focus on market imperfections and market failures • Ideology that no actor exercises power over others in a “market economy” • Firms as passive actors in the economy that respond to the dictates of technology and markets (summation of the given utility functions of individuals) • Economists trained to find equilibrium conditions (constrained optimization), and avoid the analysis of change (historical transformation) Lazonick: UMass Lowell The illusion of analyzing reality Economists have appeared to recognize reality of large-scale enterprise in monopoly theory : • departure from the perfectly competitive ideal • restrict output, raise prices • theoretical foundation of 20th century anti-trust policy •but theory of monopoly is fundamentally flawed Lazonick: UMass Lowell Schumpeter on the “Monopoly Model” “What we have got to accept is that [the large-scale enterprise] has come to be the most powerful engine of [economic] progress and in particular of the long-run expansion of total output not only in spite of, but to a considerable extent through, the strategy that looks so restrictive when viewed in the individual case and from the individual point in time. In this respect, perfect competition is not only impossible but inferior, and has no title to being set up as a model of ideal efficiency.” Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, p. 106. Lazonick: UMass Lowell p = price; q = output m = monopolist; c = perfectly competitor pmin = minimum breakeven price qmax = maximum breakeven output average revenue marginal marginal revenue p p cost 2 average cost By transforming high fixed costs into low unit costs, IF can achieve lower costs and higher output than PCs that optimize subject to constraints. The low-cost, high-output IF becomes a “monopolist”! innovating firm (IF) m c perfect competitors (PCs) pmin c q m qc 1 Monopoly means lower output and higher prices = inferior performance. But how did the monopolist gain a dominant market position? qmax c 3 THE LOGICAL FLAW: It is invalid to assume that the cost structures of “competitive” firms would be the same as those of enterprises that are dominant in an industry. Lazonick: UMass Lowell The flaw in the monopoly model Marshall on the “Monopoly Model” The “Monopoly Model” emerged out of post-Marshallian economics. But Marshall himself recognized the flaw. Alfred Marshall, Principles of Economics, Ninth edition, Macmillan, 1961, 484-485. WHAT THE MODEL ARGUES: “The monopolist would lose all his monopoly revenue if he produced for sale an amount so great that its supply, as here defined, was equal to its demand price: the amount which gives the maximum monopoly revenue is always considerably less than that. It may therefore appear as though the amount produced under a monopoly is always less and its price to the consumer always higher than if there were no monopoly. But this is not the case.” Lazonick: UMass Lowell Marshall on monopoly, continued WHY THE MODEL IS FLAWED: “For when the production is all in the hands of one person or company, the total expenses involved are generally less than would have to be incurred if the same aggregate production were distributed among a multitude of comparatively small rival producers. They would have to struggle with one another for the attention of the consumers, and would necessarily spend in the aggregate a great deal more on advertising in all its various forms than a single firm would; and they would be less able to avail themselves of the many various economies which result from production on a large scale. In particular they could not afford to spend as much on improving methods of production and the machinery used in it, as a single large firm which knew that it was certain itself to reap the whole benefit of any advance it made.” Lazonick: UMass Lowell Marshall on monopoly, continued MONOPOLY AUGMENTS OUTPUT, REDUCES PRICE: “This argument does indeed assume the single firm to be managed with ability and enterprise, and to have an unlimited command of capital – an assumption which cannot always be fairly made. But where it can be made, we may generally conclude that the supply schedule for the commodity, if not monopolized, would show higher supply prices than those of our monopoly supply schedule; and therefore the equilibrium amount of the commodity produced under free competition would be less than that for which the demand price is equal to the monopoly supply price.” Marshall adds in a footnote (485n): “Something has already been said (IV, XI, XII; and V, XI), as to the advantages which a single powerful firm has over its smaller rivals in those industries in which the law of increasing return acts strongly; and as to the chance which it might have of obtaining a practical monopoly of its own branch of production, if it were managed for many generations together by people whose genius, enterprise and energy equalled those of the original founders of the business.” Lazonick: UMass Lowell Lessons for the poorer economies Important lessons? For one, the theory of innovative enterprise provides a rationale for infant industry protection; but the infant industry argument lacks substance if it is a) just based on state policy, and b) does not explain how indigenous innovation results in competitive advantage even as it raises the incomes of participants in the process Lazonick: UMass Lowell My ultimate goal: not to understand changing business models but rather the process of economic development; have to understand the role of business organization in the development of the advanced economies to understand the problems and possibilities of that the less advanced economies face price, cost Like the theory of innovative enterprise, the infant industry argument depends on the transformation of competitive disadvantage into competitive advantage average cost marginal cost p c innovative enterprise in a once-poor economy (a grown-up infant) marginal and average pmin revenue c q c output Lazonick: UMass Lowell Theory of innovative enterprise and the infant industry argument established firm, advanced economy qmax c Technological and market conditions given by cost and revenue functions. Theory says that poor nation should compete in industries in which it has comparative advantage. Innovative enterprise can transform technologies and markets to generate higher quality, lower cost products. Protection that supports innovation can enable poor nation to gain competitive advantage. Indigenous innovation and economic development “Indigenous innovation” can occur when national institutions support business enterprises in confronting technological, market, and competitive uncertainty and engaging in collective and cumulative learning Well-developed product, labor, and capital markets are outcomes of the innovation process Indeed to generate innovation, the business enterprise uses strategy, organization, and finance to exercise control over product, labor, and capital markets Lazonick: UMass Lowell Indigenous innovation and economic development Social characteristics of a mode of resource allocation: who makes allocation decisions? what kind of investments do they make? how are the returns from those investments distributed? Specifics of “who, what and how” of innovative enterprise will differ across industries over time, and in different institutional environments -- but social conditions of innovative enterprise are general principles that are central to the study of economic development Lazonick: UMass Lowell

![Jeffrey C. Hall [], G. Wesley Lockwood, Brian A. Skiff,... Brigh, Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, Arizona](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/013086444_1-78035be76105f3f49ae17530f0f084d5-300x300.png)