The Isthmus of Panama: a major physical barrier to gene... highly mobile pantropical seabird T. E. STEEVES,

advertisement

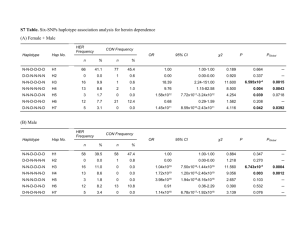

doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.00906.x The Isthmus of Panama: a major physical barrier to gene flow in a highly mobile pantropical seabird T. E. STEEVES,* D. J. ANDERSON & V. L. FRIESEN* *Department of Biology, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada Department of Biology, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, USA Keywords: Abstract gene divergence; masked booby; MDIV; mitochondrial control region; phylogeography; population divergence. To further test the hypothesis that the Isthmus of Panama is a major barrier to gene flow in pantropical seabirds, we applied phylogeographic methods to mitochondrial control sequence variation in masked booby (Sula dactylatra) populations on either side of the Isthmus of Panama and the southern tip of Africa. In accord with Steeves et al. (2003), we found that all Caribbean masked boobies with the ‘secondary contact’ cytochrome b haplotype (m-B) shared a control region haplotype (Sd_100), which grouped with Indian– Pacific haplotypes and not Caribbean–Atlantic haplotypes. In addition, Sd_100 was more closely related to control region haplotypes in the Indian Ocean than in the Pacific. We also found that the ‘secondary contact’ birds diverged more recently from extant populations in the Indian Ocean than in the Pacific. Thus, it appears that these masked boobies did not breach the Isthmus of Panama. Rather, birds likely dispersed around the southern tip of Africa during favourable oceanographic conditions in the Pleistocene. Introduction The emergence of the Isthmus of Panama approximately 3 million years ago (Coates & Obando, 1996) isolated Pacific and Atlantic populations of many tropical marine taxa (e.g. sea urchins – Lessios et al., 1999; McCartney et al., 2000; Lessios et al., 2001; fishes – Bowen et al., 2001; Muss et al., 2001; sea turtles – Bowen et al., 1992,1998). Despite the great dispersal potential of many seabirds (e.g. Anderson, 1993; Schreiber et al., 2002), recent phylogeographic studies indicate that the Isthmus of Panama is also an effective barrier to gene flow in several pantropical species (i.e. terns – Avise et al., 2000; boobies – Steeves et al., 2003). However, the divergence of extant Pacific and Atlantic populations does not correspond to the closure of the Panamanian Seaway. Rather, populations appear to have diverged within the last c. 640 000 years (Avise et al., 2000; Steeves et al., 2003). These results suggest that the Isthmus of Panama has restricted gene flow between Pacific and Atlantic Correspondence: T. E. Steeves, School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand. Tel.: +64-3-364-2987 ext. 7019; fax: +64-3-364-2590; e-mail: tammy.steeves@canterbury.ac.nz 1000 pantropical seabird populations in one of two ways: it has either never been breached (e.g. species arose following the emergence of the Isthmus of Panama and subsequently spread between the Pacific and Atlantic via the Indian Ocean), or it has rarely been breached (e.g. species spread between the Pacific and Atlantic via dispersal over the Isthmus of Panama; Steeves et al., 2003). There are several reasons to suspect that the Isthmus of Panama has never been breached. Despite their high mobility, pantropical seabirds avoid flight over land. Although the Isthmus of Panama is only 35 km at its narrowest, its interior is dominated by steep, rugged mountains and upland plains. In addition, the present width of the landbridge represents an interglacial minimum: during the glacial periods that dominated the Pleistocene, when global sea levels dropped an average of 120 m below present levels (Siddall et al., 2003), the narrowest section of the Isthmus of Panama would have been c. 200 km wide. Global sea level was higher than present during some interglacial periods but it rarely exceeded 10 m above current levels (Karner et al., 2002). Thus, although the minimum width of the Isthmus of Panama may have decreased slightly during some of these periods, the topography of its interior terrain would have remained relatively unchanged. For these reasons, J. EVOL. BIOL. 18 (2005) 1000–1008 ª 2005 EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY Physical barriers to gene flow in masked boobies any dispersal over the Isthmus of Panama would likely be passive and occur only during stochastic events such as severe storms. In contrast, fluctuating oceanographic conditions during the Pleistocene suggest that active dispersal around the southern tip of Africa is more plausible. For many tropical marine taxa, the cold Benguela Current off southwestern Africa has restricted gene flow between Atlantic and Indian Ocean populations since its appearance in the Late Pliocene (e.g. Bowen et al., 1992; Lessios et al., 1999; McCartney et al., 2000; Bowen et al., 2001, but see also Lessios et al., 2001). However, recent paleoceanographic studies indicate that whereas the Benguela Current had a tendency to weaken and/or shift northwards during major transitions from glacial to interglacial conditions in the Middle – Late Pleistocene, the warm Agulhas Current off southeastern Africa had a tendency to strengthen and intrude into the Atlantic (Flores et al., 1999; Pierre et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2002). Such warm-water intrusions, albeit ephemeral, may have facilitated active dispersal of highly mobile tropical marine taxa between the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean. Indeed, a recent phylogeographic study of olive ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea), a pantropical marine species, revealed that dispersal around the southern tip of Africa did occur within the last c. 300 000 years (Bowen et al., 1998). Previous researchers were unable to test the hypothesis that the Isthmus of Panama has not been breached by pantropical seabirds due to restricted sampling (Steeves et al., 2003) or limited genetic resolution (Avise et al., 2000). Steeves et al. (2003) examined mitochondrial cytochrome b sequence variation in red-footed (Sula sula), brown (Sula leucogaster), and masked (Sula dactylatra) boobies from the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. With the exception of one haplotype in masked boobies (m-B), no haplotypes were shared across the Isthmus of Panama in any of the three species. However, due to the absence of samples from the Indian Ocean, Steeves et al. (2003) could not determine whether boobies initially dispersed between the Pacific and the Caribbean around the southern tip of Africa or over the Isthmus of Panama. For masked boobies, because the most common Pacific haplotype (m-B) was distantly related to the two unique Caribbean haplotypes (m-C and m-D), Steeves et al. (2003) attributed the presence of haplotype m-B in the Caribbean to secondary contact, but were unable to determine whether secondary dispersal occurred via the Indian Ocean or over the Isthmus of Panama. Subsequent analyses revealed that masked boobies from the western Indian Ocean also share cytochrome b haplotype m-B (n ¼ 6; TES, unpublished data). Thus, additional analyses that examine sequence variation in a more rapidly evolving gene (e.g. mitochondrial control region) are required to determine whether masked boobies breached the Isthmus of Panama within the last c. 640 000 years. 1001 In this study, we expand on Steeves et al. (2003) and examine mitochondrial control region sequence variation among masked booby populations on either side of the Isthmus of Panama and the southern tip of Africa to further test the hypothesis that the Isthmus of Panama is a major barrier to gene flow in pantropical seabirds by addressing the following predictions: (a) If the presence of cytochrome b haplotype m-B in the Caribbean is due to secondary contact then Caribbean masked boobies with cytochrome b haplotype m-B will have control region haplotypes that are more closely related to haplotypes found in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific than to haplotypes found in the Caribbean. In addition, time since secondary divergence will be more recent than time since initial divergence of Caribbean masked boobies and masked boobies in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific. (b) If secondary dispersal occurred around the southern tip of Africa (i.e. not over the Isthmus of Panama) then Caribbean masked boobies with the ‘secondary contact’ cytochrome b haplotype m-B will have control region haplotypes that are more closely related to haplotypes found in the Indian Ocean than to haplotypes found in the Pacific. In addition, the ‘secondary contact’ birds will have diverged more recently from extant populations in the Indian Ocean than populations in the Pacific. Methods Sampling and laboratory protocols Blood or feather samples were collected from 120 masked boobies in the Caribbean Sea (Isla Monito; Steeves et al., 2003), the Atlantic Ocean (Ascension Island; this study), the western Indian Ocean (Cosmoledo Atoll; this study), and the eastern Pacific Ocean (Isla San Benedicto; this study; Fig. 1). DNA was purified from samples using standard phenol/chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation (Sambrook et al., 1989). To avoid nuclear copies of the mitochondrial control region, we amplified and sequenced a fragment that included the 3¢ end of the ND6 gene, the complete tRNAglu gene as well as all of Domain I and most of Domain II of the control region in a subset of the feather samples using a general light-strand primer designed for birds (ND6L-end, O. Haddrath, unpublished) and a more species-specific heavy-strand primer designed for northern gannets (Morus bassanus, SbMCR-H800, 5¢-CCAATACGTCAACCGTCTCAT-3¢). To confirm the mitochondrial origin of these sequences, we compared them to published ND6, tRNAglu, and control region sequences and identified all of the avian conserved blocks in Domain II (Desjardin & Morais, 1990; Baker & Marshall, 1997; Randi & Lucchini, 1998). We then developed two species-specific primers (SdMCRL100B, 5¢-AATTCGTGGAAGCAGTCACA-3¢; SdMCRH750, 5¢-GGGAACCAAAAGAGGAAAACC-3¢) to amplify J. EVOL. BIOL. 18 (2005) 1000–1008 ª 2005 EUROPEAN SOCIETY FOR EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY 1002 T. E. STEEVES ET AL. Fig. 1 Sampling locations for masked boobies. 1: Caribbean Sea (Isla Monito); 2: Atlantic Ocean (Ascension Island); 3: western Indian Ocean (Cosmoledo Atoll): 4: eastern Pacific Ocean (Isla San Beneditco). a 500 bp fragment (Domain I ¼ 283 bp, Domain II ¼ 217 bp) in all available samples. PCR amplifications were performed in 25–50 lL reaction volumes containing 5 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.8, 5 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl, 0.01% gelatin, 125 lg BSA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.4 lM of each primer, 0.5–1 U Taq DNA Polymerase (Roche, Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and c. 100 ng of extracted DNA using the following temperature profile: 30 s at 95 C, 30 s at 55 C–60 C and 45 s–1 min at 72 C for 30 cycles preceded by a 2 min denaturing step at 95 C and followed by a 3 min extension step at 72 C. PCR products were sequenced using standard cycle sequencing protocols (Mobix, McMaster University) and visualized using an ABI 373A automated sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Applied Biosystems Division, Foster City, CA, USA). Data analyses Control region sequences were aligned manually using Se-Al (Rambaut, 1996) and all variable sites were confirmed by visual inspection of the chromatograms. Twelve ambiguous sites in 16 individuals were resolved as follows: if the haplotype sequence containing the ambiguous site (e.g. C/T, haplotype 1) was otherwise identical to a haplotype sequence without the ambiguous site (e.g. C, haplotype 2), then the nucleotide was assigned the nonambiguous base (e.g. haplotype 1 ¼ haplotype 2; Moum & Árnason, 2001); if the haplotype sequence containing the ambiguous site (e.g. C/T, haplotype 1) was otherwise identical to two haplotypes without the ambiguous site (e.g. C, haplotype 2; T, haplotype 3), then the nucleotide was assigned the nonambiguous base present in the most common and/or most basal haplotype (e.g. if haplotype 3 was more common and basal to haplotype 2 then haplotype 1 ¼ haplotype 3). Excluding these 16 individuals from all subsequent analysis does not alter our conclusions (data not shown). Relationships among control region haplotypes were inferred by constructing statistical parsimony networks in TCS (Version 1.13, Clement et al., 2000). For population-level analyses, we defined six putative populations: Caribbean (excluding secondary contact birds), Caribbean (secondary contact birds only), Atlantic (excluding secondary contact birds), Atlantic (secondary contact birds only), western Indian, and eastern Pacific. Net genetic distance among population pairs was estimated as d ¼ pxy – 0.5 (px + py), where pxy is mean percentage sequence divergence between populations x and y, and px and py are mean percentage sequence divergence within populations x and y, respectively (Nei, 1987) using ARLEQUIN (Version 2.001; Schneider et al., 2001). Statistical significance of genetic distances was assessed by randomization using 1000 permutations. Nielsen & Wakeley (2001) recently developed a program (MDIV) based on coalescent theory (Kingman, 1982a,b) that employs Bayesian inference to simultaneously estimate theta (Q, measured as 2Nel where Ne is the effective mitochondrial population size and l is the mutation rate per gene per year), divergence time (T, measured as t/Ne where t is the time since population divergence), and time to most recent common ancestor (TMRCA, measured as tMRCA/Ne where tMRCA is the time since gene divergence) for population pairs under a finite sites model. Whereas T estimates when two populations diverged from one another (i.e. population divergence), TMRCA estimates when genes last shared a common ancestor (i.e. gene divergence; Edwards & Beerli, 2000) and can be used as a proxy for ancestral population age (Griswold & Baker, 2002). We used MDIV to estimate Q, T, and TMRCA among population pairs on either side of the Isthmus of Panama and the southern tip of Africa. For each pairwise comparison, a minimum of three chains (length of Markov chain ¼ 5 000 000 cycles; burn-in time ¼ 500 000 cycles) with different random seeds were run using the following parameters: J. EVOL. BIOL. 18 (2005) 1000–1008 ª 2005 EUROPEAN SOCIETY FOR EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY Physical barriers to gene flow in masked boobies I 1003 III Sd_100 Fig. 2 Statistical parsimony networks (I–III) among masked booby haplotypes estimated by TCS. Circle sizes are proportional to frequencies of haplotypes given in Table S1. Filled circles represent missing haplotypes. Gray line indicates the only alternative connection. Arrow denotes haplotype Sd_100 (see text for details). II Caribbean finite sites model (HKY, Hasegawa et al., 1985), Mmax ¼ 5 or 10 (where M ¼ migration rate), and Tmax ¼ 5, 10 or 20. For each pairwise comparison, values for Mmax and Tmax were selected as those that generated a posterior distribution of the correct shape (e.g. a bell-shaped curve), but minimized the relative number of data points on the right-hand tail. T and Q were estimated as the mode of their respective posterior distributions (MDIV provides a point estimate only for TMRCA; Nielsen & Wakeley, 2001). We calculated a Bayesian confidence interval, or credibility interval (CI), for Q (Nielsen & Wakeley, 2001), but we did not calculate a credibility interval for T: credibility intervals for T are highly sensitive to set values of Tmax because the right-hand tail of the probability distribution decreases to zero very slowly. Rather, we compared pairwise estimates of T by plotting their respective posterior distributions and visually inspecting the degree of overlap. Pairwise estimates of T and TMRCA were converted to time since divergence in years before present (y bp) using t ¼ TQ/ 2l and tMRCA ¼ TMRCAQ/2l assuming a typical avian divergence rate of 15% per million years (my) for Domain I and Domain II combined (for 500 bp, l ¼ 0.0000375; Wenink et al., 1996). To test the assumption that our estimates of time since initial divergence reflect historical isolation and not past selective pressures (i.e. mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in masked boobies is neutral), Tajima’s D (Tajima, 1989) and Fu & Li’s D* and F* (Fu & Li, 1993) were calculated for all populations (excluding secondary contact birds) and statistical significance of test statistics were assessed using DnaSP (Version 4.0; Rozas et al., 2003). Whereas significant positive values may indicate Atlantic W. Indian E. Pacific balancing selection or population subdivision, significant negative values may indicate recent selective sweeps or population bottlenecks (Tajima, 1989; Fu & Li, 1993). Excluding one test statistic for one population (Atlantic masked boobies, D* ¼ 1.58, P < 0.05; positive significant value likely due to one relatively frequent divergent haplotype, see Fig. 2), all test statistics for all populations were nonsignificant. Thus, we found little evidence to contradict the assumption of neutrality. Results Among the 120 masked booby samples, we found 52 control region haplotypes defined by 83 variable sites including 75 transitions, 7 transversions, and 3 indels (Table S1). All haplotypes were unique to a single sampling location (Table S1). Three statistical parsimony networks were estimated by TCS (95% parsimony probability connection limit equals nine steps; Fig. 2). Network I contained the majority of haplotypes from the Caribbean and Atlantic, network II contained one haplotype from the Caribbean (Sd_104), and network III contained all haplotypes from the western Indian and eastern Pacific as well as one haplotype from the Caribbean (Sd_100). The minimum number of steps between networks I and II, I and III, and II and III was 11, 35 and 36, respectively. Within network I, we found two relatively distinct phylogeographic clades: one clade contained the majority of haplotypes from the Caribbean and the other contained the majority of haplotypes from the Atlantic. Within network III, we also found two relatively distinct clades: one clade contained all of the haplotypes from the eastern Pacific and one haplotype J. EVOL. BIOL. 18 (2005) 1000–1008 ª 2005 EUROPEAN SOCIETY FOR EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY 1004 T. E. STEEVES ET AL. from the western Indian (Sd_64), and the other clade contained the remainder of the haplotypes from the western Indian and one haplotype from the Caribbean (Sd_100). Sd_100 was found in all Caribbean samples with secondary contact cytochrome b haplotype m-B and was more closely related to haplotypes from the western Indian Ocean than to haplotypes from the eastern Pacific (i.e. Sd_100 was connected by a minimum of three steps to interior haplotypes that were closely connected to haplotypes from the western Indian, whereas it was connected by a minimum of nine steps to interior haplotypes that were closely connected to haplotypes from the eastern Pacific). Because network III did not contain Atlantic control region haplotypes, we inferred that secondary contact cytochrome b haplotype m-B was not present in the Atlantic (results confirmed in subsequent analysis of cytochrome b sequence variation for a subset of Atlantic samples; data not shown). Similarly, we inferred that neither cytochrome b haplotype m-C or m-D was present in either the Pacific or the Indian Ocean, based on subsequent analysis of control region sequence variation among nine additional Indo-Pacific populations (n ¼ 228; T.E. Steeves, D.J. Anderson & V.L. Friesen, unpublished). Thus, we estimated sequence divergence within and between five populations only: Caribbean (excluding secondary contact birds), Caribbean (secondary contact birds only), Atlantic, western Indian, and eastern Pacific. Estimates of px were relatively high (px ¼ 0.91–1.38; Table 1), excluding the secondary contact birds (px ¼ 0.00; Table 1). All pairwise estimates of d were significantly greater than zero: estimates between the Caribbean–Atlantic region and the Indian–Pacific region were relatively high and comparable to estimates between secondary contact birds and birds in the Caribbean and the Atlantic (d ¼ 6.80–7.37; Table 1); in contrast, estimates between the Caribbean and the Atlantic, and between the Indian and the Pacific were relatively low, and comparable to estimates between secondary contact Table 1 Estimates of mean percentage sequence divergence within populations (px, along diagonal in bold), mean percentage sequence divergence among populations (pxy, above diagonal), and corrected mean percentage divergence among populations (d, below diagonal) for masked booby populations on either side of the Isthmus of Panama and the southern tip of Africa. Caribbean* Caribbean Atlantic Western Indian Eastern Pacific Caribbean* Caribbean Atlantic Western Indian Eastern Pacific 1.26 7.10 0.80 6.80 7.27 7.73 0.00 7.10 1.00 2.03 1.89 7.55 0.91 6.86 7.37 8.12 1.69 8.00 1.38 1.00 8.38 2.50 8.30 2.17 0.95 All pairwise estimates of d were significantly greater than zero (all P < 0.01). *Excluding secondary contact birds. Secondary contact birds only. birds and birds in the western Indian and the eastern Pacific (d ¼ 0.80–2.03; Table 1). Because we aimed to compare estimates of time since initial divergence and time since secondary divergence, we restricted our population pairwise comparisons to Caribbean (excluding secondary contact birds) vs. western Indian and eastern Pacific, and Caribbean (secondary contact birds only) vs. western Indian and eastern Pacific, respectively. For all pairwise comparisons, although very large values of T cannot be excluded, probability distributions for T and Q showed a small degree of overlap (Figs 3 and 4). For the Caribbean (excluding secondary contact birds) comparisons, whereas the point estimate of T for the Caribbean vs. the eastern Pacific was c. twice as high as for the Caribbean vs. the western Indian (5.64 and 2.88, respectively; Fig. 3a), the point estimate of Q was c. 50% lower (6.37 (CI ¼ 4.36–10.72) and 11.58 (CI ¼ 7.99–18.37), respectively; Fig. 4a). Thus, estimates of time since initial divergence of masked boobies on either side of the Isthmus of Panama and the southern tip of Africa were similar; estimates of tMRCA showed a concordant pattern (Table 2). For the Caribbean (secondary contact birds only) comparisons, the point estimate of Q for the Caribbean vs. the eastern Pacific was also c. half that for the Caribbean vs. the western Indian (4.80 (CI ¼ 2.87–8.85) and 9.13 (CI ¼ 6.04–16.34), respectively; Fig. 4b), but the point estimate of T was c. six times higher (2.08 and 0.35, respectively; Fig. 3b). Thus, the estimate of time since secondary contact for the Caribbean vs. western Indian comparison was c. three times more recent than for the Caribbean vs. the eastern Pacific comparison; in contrast, estimates of tMRCA were similar (Table 2). Discussion Secondary contact in masked boobies We found that all Caribbean masked boobies with the secondary contact cytochrome b haplotype m-B had the same control region haplotype (Sd_100) and, in accord with Steeves et al. (2003), Sd_100 grouped with haplotypes from the western Indian–eastern Pacific region (rather than with haplotypes from the Caribbean–Atlantic region; Fig. 2). We also found that time since secondary divergence was more recent than time since initial divergence of extant masked booby populations on either side of the Isthmus of Panama and the southern tip of Africa (Table 2). More importantly, the secondary contact haplotype (Sd_100) was more closely related to western Indian haplotypes than to eastern Pacific haplotypes (Fig. 2), and the secondary contact birds diverged more recently from birds in the western Indian than from birds in the eastern Pacific (Table 2). Our combined results indicate that the presence of Sd_100 in the Caribbean is due to a secondary dispersal event from the western Indian Ocean around the southern tip of J. EVOL. BIOL. 18 (2005) 1000–1008 ª 2005 EUROPEAN SOCIETY FOR EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY (a) 0.006 (a) 0.020 Posterior probability Physical barriers to gene flow in masked boobies 0.015 1005 Posterior probability 0.005 0.004 0.003 0.002 0.010 0.005 0.001 0.000 0.000 0 5 10 15 0 20 10 20 40 Θ (b) 0.004 (b) 0.003 Posterior probability T Posterior probability 30 0.002 0.012 0.008 0.004 0.001 0.000 0.000 0 2 4 6 8 10 0 5 Africa into the Caribbean Sea, likely during a period when the cold Benguela Current off southwestern Africa was relatively weak and the warm Agulhas Current off southeastern Africa was relatively strong. Assuming that pairwise estimates of tMRCA are a good proxy for ancestral population age and that population divergence occurs after gene flow ceases, we estimate 15 20 25 Θ T Fig. 3 Posterior probabilities for divergence time (T) among masked boobies on either side of the Isthmus of Panama and the southern tip of Africa. (a) Excluding secondary contact birds: pairwise comparisons between Caribbean vs. western Indian (open triangles) and Caribbean vs. eastern Pacific (open circles); (b) Secondary contact birds only: pairwise comparisons between Caribbean vs. western Indian (open triangles) and Caribbean vs. eastern Pacific (open circles). 10 Fig. 4 Posterior probabilities for theta (Q) among masked boobies on either side of the Isthmus of Panama and the southern tip of Africa. (a) Excluding secondary contact birds: pairwise comparisons between Caribbean vs. western Indian (open triangles) and Caribbean vs. eastern Pacific (open circles); (b) Secondary contact birds only: pairwise comparisons between Caribbean vs. western Indian (open triangles) and Caribbean vs. eastern Pacific (open circles). that the secondary contact event occurred within the last c. 43 000 – 183 000 years. Although these dates are approximate and should be confirmed using additional unlinked loci (e.g. multiple single nucleotide polymorphisms; Brumfield et al., 2003), we suggest that secondary dispersal likely occurred during the transition from the glacial conditions of marine isotope stage 6 and the interglacial conditions of marine isotope substage 5e (i.e. J. EVOL. BIOL. 18 (2005) 1000–1008 ª 2005 EUROPEAN SOCIETY FOR EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY 1006 T. E. STEEVES ET AL. Table 2 Estimates of time since divergence (t) and time to most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) among masked booby populations on either side of the Isthmus of Panama and the southern tip of Africa. Caribbean* Caribbean Region T (ybp) tMRCA (ybp) t (ybp) tMRCA (ybp) Western Indian Eastern Pacific 444 672 479 024 595 984 641 413 42 606 133 120 182 600 197 120 *Excluding secondary contact birds. Secondary contact birds only. Termination II: c. 130 000 years ago). Multiple paleoindicators (i.e. foraminifera assemblages and foraminifera oxygen isotopes) in sediment cores collected from the Benguela Current (Pierre et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2002) and from the Agulhas Current Retroflection (Flores et al., 1999) indicate that during several major Pleistocene deglaciation events, including Termination II, warm water pulsed around the southern tip of Africa. Initial divergence of masked boobies We estimate that the initial divergence of extant masked booby populations on either side of the Isthmus of Panama and the southern tip of Africa occurred within the last c. 479 000 years (Table 2). Steeves et al. (2003) estimated that masked booby populations in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean diverged within the last c. 460 000 – 640 000 years, assuming a sulid-specific divergence rate of 2.8%my)1 for cytochrome b or a more typical avian rate of 2%my)1, respectively. Although the latter estimates were derived using traditional population genetic methods (Wilson et al., 1985) and reflect both gene and population divergence (i.e. total divergence; Edwards & Beerli, 2000; Arbogast et al., 2002), we attribute the similarity of our estimates and those of Steeves et al. (2003) to the relatively young age of ancestral masked booby populations (Table 2). Edwards & Beerli (2000) and Arbogast et al. (2002) cautioned that the ratio of gene divergence to population divergence between recently diverged populations can be extremely high, depending on the size of the ancestral population. We add that this ratio will also depend on the age of the ancestral population: if the ancestral population is relatively young, then population divergence may contribute to a larger fraction of the total divergence between two recently diverged populations. Although masked boobies in the Caribbean Sea (excluding secondary contact birds) appear to have diverged more recently from birds in the western Indian Ocean than from birds in the eastern Pacific Ocean (Table 2), overlapping credibility intervals for both T and Q (Figs 3a and 4a) preclude the conclusion that the Isthmus of Panama has never been breached by masked boobies. In addition, because the paleoceanographic record for fora- minifera is largely restricted to the last c. 500 000 years (Flores et al., 1999; Pierre et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2002), further speculation regarding the initial dispersal route of masked boobies, either in or out of the Caribbean Sea, c. 445 000 – 641 000 years ago (Table 2) is difficult. Regardless, the Isthmus of Panama has clearly not been breached by several species of highly mobile pantropical seabirds in hundreds of thousands of years (Avise et al., 2000; Steeves et al., 2003, this study). In contrast, fluctuating oceanographic conditions around the southern tip of Africa likely enabled secondary dispersal by masked boobies from the Indian Ocean into the Caribbean Sea within the last c. 183 000 years. Acknowledgments We gratefully acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their invaluable contributions to this study: G. Rocamora for collecting tissue samples; US Fish and Wildlife Service, US Coast Guard, and Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources for logistical support in Puerto Rico; Royal Society for the Protection of Birds for logistical support on Ascension; Island Conservation and Ecology Group, Grupo de Ecologı́a y Conservación de Islas, and Spight Family Foundation for logistical support in Mexico; T. Loxton, N. Ratcliffe, and R. White for field assistance on Ascension; M. Amin Ordoñez, A. Hebshi, and S. Hebshi for field assistance in Mexico; T. Birt, S. Garner, O. Haddrath, and R. Kristensen for laboratory assistance; J. Pillardy for technical assistance regarding MDIV analyses; J. Brown and R. Nielsen for helpful discussions regarding Bayesian statistics; A. Mix and P. Werner for advice regarding interpretation of paleoceanographic data, and T. Burg for many helpful general discussions and comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript. Funding was supplied by American Museum of Natural History (Frank M. Chapman Memorial Grant to TES), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Discovery Grants to VLF and Post-Graduate Scholarship to TES), Premier’s Research Excellence Award (to VLF), Queen’s University (Graduate Dean’s Doctoral Field Travel Grants and Pearl E. Williams and Llewellyn Hillis Grant to TES), and Wake Forest University Sullivan Fund (to DJA). Supplementary material The following material is available from http:// www.blackwellpublishing.com/products/journals/suppmat/ JEB/JEB906/JEB906sm.htm Table S1 Frequencies and variable sites among 52 masked booby control region haplotypes. References Arbogast, B.S., Edwards, S.V., Wakeley, J., Beerli, P. & Slowinski, J.B. 2002. Estimating divergence times from J. EVOL. BIOL. 18 (2005) 1000–1008 ª 2005 EUROPEAN SOCIETY FOR EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY Physical barriers to gene flow in masked boobies molecular data on phylogenetic and population genetic timescales. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 33: 707–740. Anderson, D.J. 1993. Masked booby (Sula dactylatra). In: The Birds of North America, No. 73 (A. Poole & F. Gill, eds), pp. 1–16. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia. Avise, J.C., Nelson, W.S., Bowen, B.W. & Walker, D. 2000. Phylogeography of colonially nesting seabirds, with special reference to global matrilineal patterns in the sooty tern (Sterna fuscata). Mol. Ecol. 9: 1783–1792. Baker, A.J. & Marshall, H.D. 1997. Mitochondrial control region sequences as tools for understanding evolution. In: Avian Molecular Evolution and Systematics (D. P. Mindell, ed.), pp. 51– 82. Academic Press, New York. Bowen, B.W., Meylan, A.B., Ross, P., Limpus, C.J., Balazs, H. & Avise, J.C. 1992. Global population structure and natural history of the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) in terms of matriarchal phylogeny. Evolution 46: 865–881. Bowen, B.W., Clark, A.M., Abreu-Grobois, F.A., Chaves, A., Reichart, H.A. & Ferl, R.J. 1998. Global phylogeography of the ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys spp.) as inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Genetica 101: 179–189. Bowen, B.W., Bass, A.L., Rocha, L.A., Grant, W.S. & Robertson, D.R. 2001. Phylogeography of the trumpetfishes (Aulostomus): ring species complex on a global scale. Evolution 55: 1029– 1039. Brumfield, R.T., Beerli, P., Nickerson, D.A. & Edwards, S.V. 2003. The utility of single nucleotide polymorphisms in inferences of population history. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18: 249– 256. Chen, M.T., Chang, Y.P., Chang, C.C., Wang, L.W., Wang, C.H. & Yu, E.F. 2002. Late quarternary sea-surface temperature variations in the southeast Atlantic: a planktic foraminifer faunal record of the past 600 000 yr (IMAGES II MD962085). Mar. Geol. 180: 163–181. Clement, M., Posada, D. & Crandall, K.A. 2000. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 9: 1657–1659. Coates, A.G. & Obando, J.A. 1996. The geologic evolution of the Central American Isthmus. In: Evolution and Environment in Tropical America (J. B. C. Jackson, A. F. Budd & A. G. Coates, eds), pp. 21–56. University of Chicago, Chicago. Desjardin, P. & Morais, R. 1990. Sequence and gene organization of the chicken mitochondrial genome: a novel gene order in higher vertebrates. J. Mol. Biol. 212: 599–634. Edwards, S.V. & Beerli, P. 2000. Perspective: gene divergence, population divergence, and the variance in coalescence time in phylogenetic studies. Evolution 54: 1839–1854. Flores, J.A., Gersonde, R. & Sierro, F.J. 1999. Pleistocene fluctuations in the Agulhas Current retroflection based on the calcareous plankton record. Mar. Micropaleontol. 37: 1–22. Fu, Y.X. & Li, W.H. 1993. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics 133: 693–709. Griswold, C.K. & Baker, A.J. 2002. Time to most recent common ancestor and divergence times of populations of common chaffinches (Fringilla coelebs) in Europe and North Africa: insights into Pleistocene refugia and current levels of migration. Evolution 56: 143–153. Hasegawa, M., Kishino, H. & Yano, T. 1985. Dating of the human–ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 21: 160–174. Karner, D.B., Levine, J., Medeiros, B.P. & Muller, R.A. 2002. Constructing a stacked benthic d18O record. Paleoceanography 17: 1030 (doi:10.1029/2001PA000667). 1007 Kingman, J.F.C. 1982a. The coalescent. Stoch. Proc. Appl. 13: 235–248. Kingman, J.F.C. 1982b. On the genealogy of large populations. J. Appl. Prob. 19: 27–43. Lessios, H.A., Kessing, B.D., Roberston, D.R. & Paulay G. 1999. Phylogeography of the pantropical sea urchin Eucidaris in relation to land barriers and ocean currents. Evolution 53: 806– 817. Lessios, H.A., Kessing, B.D. & Pearse, J.S. 2001. Population structure and speciation in tropical seas: global phylogeography of the sea urchin Diadema. Evolution 55: 955–975. McCartney, M.A., Keller, G. & Lessios, H.A. 2000. Dispersal barriers in tropical oceans and speciation in Atlantic and eastern Pacific sea urchins of the genus Echinometra. Mol. Ecol. 9: 1391–1400. Moum, T. & Árnason, E. 2001. Genetic diversity and population history of two related seabird species based on mitochondrial DNA control region sequences. Mol. Ecol. 10: 2463–2478. Muss, A., Robertson, D.R., Stepien, C.A., Wirtz, P. & Bowen, B.W. 2001. Phylogeography of Ophioblennius: the role of ocean currents and geography in reef fish evolution. Evolution 55: 561–572. Nei, M. 1987. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. Columbia University, New York. Nielsen, R. & Wakeley, J. 2001. Distinguishing migration from isolation: a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach. Genetics 158: 885–896. Pierre, C., Saliege, J.F., Urrutiaguer, M.J. & Giraudeau, J. 2001. Stable isotope record of the last 500 k.y. at Site 1087 (Southern Cape Basin). In: Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Volume 175 (G. Wefer, W. H. Berger & C. Richter, eds), pp. 1–22 http://www-odp.tamu.edu/publications/175_SR/VOLUME/CHAPTERS/SR175_12.PDFs. Rambaut, A. 1996. Se-Al: Sequence Alignment Editor. http:// evolve.zoo.ox.ac.uk/. Randi, E. & Lucchini, V. 1998. Organization and evolution of the mitochondrial DNA control region in the avian genus Alectoris. J. Mol. Evol. 47: 449–462. Rozas, J., Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C., Messegyer, X. & Rozas, R. 2003. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 19: 2496–2497. Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E.F. & Maniatis, T. 1989. Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, New York. Schneider, S., Roessli, D. & Excoffier, L. 2001. Arlequin Ver. 2.001: a Software for Population Genetic Data Analysis. University of Geneva, Switzerland. Schreiber, E.A., Feare, C.J., Harrington, B.A., Murray, B.G., Roberston, W.B., Roberston, M.J. & Woolfenden, G.E. 2002. Sooty tern (Sterna fuscata). In: The Birds of North America, No. 665 (A. Poole & F. Gill, eds), pp. 1–31. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia. Siddall, M., Rohling, E.J., Almogi-Labin, A., Hemleben, Ch., Meischner, D., Schmeizer, I. & Smeed, D.A. 2003. Sea-level fluctuations during the last glacial cycle. Nature 423: 853–858. Steeves, T.E., Anderson, D.J., McNally, H., Kim, M.H. & Friesen, V.L. 2003. Phylogeography of Sula: the role of physical barriers to gene flow in the diversification of tropical seabirds. J. Avian Biol. 34: 217–223. Tajima, F. 1989. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123: 585–595. J. EVOL. BIOL. 18 (2005) 1000–1008 ª 2005 EUROPEAN SOCIETY FOR EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY 1008 T. E. STEEVES ET AL. Wenink, P.W., Baker, A.J., Rösner, H.U. & Tilanus, M.G.J. 1996. Global mitochondrial DNA phylogeography of Holarctic breeding dunlins (Calidris alpina). Evolution 50: 318–330. Wilson, A.C., Cann, R.L., Carr, S.M., George, M., Gyllensten, U.B., Helm-Bychowski, K.M., Higuchi, R.G., Palumbi, S.R., Prager, E.M. & Stoneking, M. 1985. Mitochondrial DNA and two perspectives on evolutionary genetics. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 26: 375–400. Received 11 February 2004; revised 8 November 2004; accepted 20 January 2005 J. EVOL. BIOL. 18 (2005) 1000–1008 ª 2005 EUROPEAN SOCIETY FOR EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY