May 2007 Assessing Federalism:

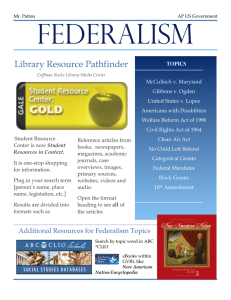

advertisement