Why Are Welfare Caseloads Falling? March

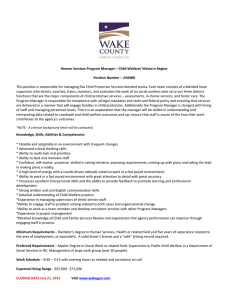

advertisement