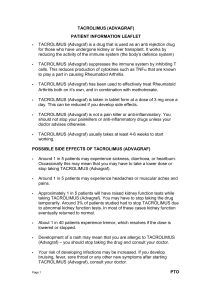

with Tacrolimus Clinical Experience Ointment in Atopic Dermatitis III

advertisement