of Copyrighted Material

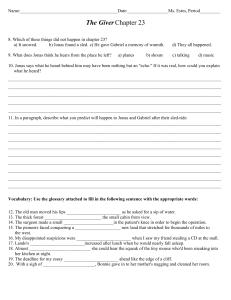

advertisement