Design, Outcomes, and Lessons Learned from the Urban Institute Academy for

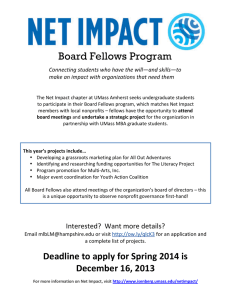

advertisement