ANTHROPOLOGY IN A FORENSIC CONTEXT Tal Simmons and William

advertisement

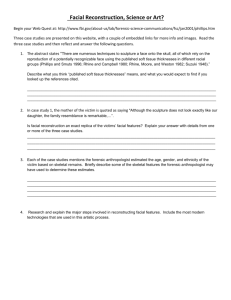

ANTHROPOLOGY IN A FORENSIC CONTEXT Tal Simmons and William D. Haglund 6.1 Background Forensic anthropology is that branch of applied physical anthropology concerned with the identification of human remains and associated skeletal trauma related t o manner of death in a legal context (Keichs 1 9 9 8 ) . In the United States. the past t w o decades have witnessed thc medico-legal community embracing forensic :~nthropologyas a forensic specialty. The traditional role of the anthropologist has been t o determine sex, race, agr, and stature of skeletal material t o assist in human identification. More recently, this niche has expanded via a major evolution into the realm of fleshed, decomposing, hurnt, and dismembered remains. Toclay, anthropologists provide expertise in the recover! of remains, assist with identification of deco~nposcdo r burnt remains, interpret trauma t o hone, assist with multiple fatality incidents, and provide court testimony. Auxiliary techniques, such as creati013 of visages from the skull and photosuperimposition often fall within the expertise of the forensic anthropologist in the USA (Haglund and Rodriguez 1998), though not in the UK where it remuins a separate specialis~u.U n f o r t ~ ~ n a t e l ythere , has been a Ing in the acceptance of archaeologists1 anthropologists in other parts of the world, including the UK, where they have barely begun their adolescent entry into the forensic community (Hunter et ill. 1996; see also Chapter 1, Section 1.3).Thus, while this chapter has wide application, much o f the casework and experience is derived from US sources. T h e acceptance of forensic anthropology in ~ 3 ninternational setting has, in contrast, a relatively long history, beginning with the 1984 investigations of Eric Stover a n d a team of forensic scientists from the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), w h o began the exhumation of mass graves in a search for thc disnppeared in Argentina (Stover a n d Kyan 2 0 0 1 ) . This work is ongoing and has also led t o the use of mtDNA comparisons of the deceased a n d living relatives for purposes of identification (Boles et nl. 1995) and has included the creation of a voluntary National Genetic Data Bank for this purpose (Stover and Ryan 2001 ). 111 Guatemala the use of torensic anthropology became established in 1991 a n d has continued t o the present where only reliitivcly recently (since 1998) have individuals heen hrought t o trill1 and the anthropological evidence heard in court. Both Argentina and Guatemala have established permanent national forensic teams as a result of the early training they received during these investigations. Stovcr, Clyde Snow and other international forensic and human rights experts were also involved in investigntions in Iraqi Kurdistan in 1991. The date that hallmarks n burgeoning of activity for anthropologistslarcheologists in the nrenki of international forensic investigations was 1996. l'his evolution was spearheaded by the eniploymcnt o t forensic specialists by the international criminal trillunals tor R\va~ida(ICTII) and the E'onl~erYugoslavia (1C:TY; see also Chapter 1 , Section 1.7 a n d Chapter 7, Section 7.7).111 1996, over 1,200 bodies in Rwanda, Croatia, ' ~ n dtlie Kepuhlika Serhska area of Bosnia in Hcrzegove~iia\vere ex-Iiumed by teams fro111 Physicians for H u n ~ a nKights (I'HR), under the auspices 0 1 the ICTR and ICTY ( H n g l u ~ ~2002). d X recently published csarnple of the use of forensic archaeology es~lminescscavations carried out by experts provided by the PHK (Connor and Scott 200 1 ). Connor and Scott discuss the Killuye ( R w a n d a ) case in sollie detail. Other chapters in tlie sanie volume (Stover and Ryan 2001; Connor and Scott 2 0 0 1 ) briefly ~ i ~ c n t i ocases n in the former Yugoslavia. As f o r e ~ ~ s nnthropologists, ic the authors have been involved in the euhunlation and identification of victims of war, ethnic cleansing andlor genocide in the former Yugoslavia, Sri Lanka, Cyprus, Guatemala, Rwanda, and many other countries. No individual forensic anthropologist acts alone in this type of investigation; rather it necessitates the cooperation of multiple agencies and organizations - many of which have c c ~ ~ ~ i p e tagendas ing or mkindates. The work is by definition multidisciplinary and it integrates all four fields of antliropology (biological, cultural and linguistic, and archaeological) as well as a variety of other disciplines including pathology, odontology, c s i ~ ~ ~ i ~ i a l i sand t i c sthe la\v. T h e political environment in wliich a11 of this takes place has, for better or worse, a great influence on the process of investigation and, ultimately on the identification of victims. There are numerous responsihilitics accorded to the torensic anthropologist involved in this process: to maintain tlie scientific integrity of the investigation; t o maintain and contorm t o the appropriate legal conventions of thc investigation; and t o fulfill hislher responsibility t o the local c o m ~ n u n i t yaffected hy the events. All three aspects are important and in many cases unique to each location and investisation, often requiring the application of different guidelines, protocols and standards and invoking new and different pressures from various agencies and individuals. In recent years, the role of the forensic anthropologist has expanded in scope within the boundaries o f the USA in the context of medico-legal investigations. It has also developed within the increasing nurnber of international human rights forensic projects with \rhich the a~lthropologicalcomn~unityhas becon~einextricably involved. While the same basic tech~~iclues are useful in both contexts, flexibility is prerequisite to conducting ~ i i o s tinvestigations. An experienced torellsic anthropologist must know how to cope with situ:itions where the ideal protocol and methodology are both followed. wen However, in situations where they are either not pragmatic or unavailable in a b' situation, helshe must know w h a t of the 'ideal' may be eliminated without losing necessary information. This chapter discusses aspects of a m i ~ i i m u me x a n ~ i n a t i o n protocol. It is not meant t o be a manual of antl~ropologicaltechniques, as it is assu~lled that personnel responsible for these tasks will have adequate training in the field of forensic anthropology. 6.2 The analysis 6.2.1 The skeletal inventon1 The first phase of the analvsis begins Lvith a skeletal inventory of the presence/absencc of each element, as well as any duplic;ltion of elements tliat night be present (indicating that there is more than one individual represented). Placing the remains in anatoniical ortlcr also allows ease of conipletion of skeletal inventory, which is criticlll to documenting and maintaining chain of custody (Figurc 6.1). This inventory should also indicate trag~nentarybones; yet thcse should not be espressed numerically as these may s~ibsequentlydisintegrate into smaller f r a g ~ n e n t sand the 'number' becomes problematic because the numbers change. The inventory must also note the condition of the remains a t this stage of the analysis, including a taphonomic assessment of postmortem damage (e.g. staining, carnivore or rodent gnawing, breakage, \veatliering, root etching, etc.). T h e condition of each element should be noted. It is recommended tliat the anthropologist prepares in advance ,I list of post-lnorteni damage likely t o be seen in forensic cases. Anticipating ~ v h a tis probably going t o be encountered allows tlie anthropologist t o predetermine h o w things will be described. While not a defining tactor in most single-case forensic work, the standardization of descriptive terminology and its recording becomes essential in mass disasters and international human rights and hulnanitarian projects which require tlie processing a n d documentation of hundreds of remains (below). Likcwise, standardized views of the skeleton should be taken as well. Such photographs should include the following: a skeletal overview of the indi~ i d u a in l anatomical order; the ~ n ~ s i l l and a r ~mandibular dentition; all elements used to esci~natethe age of a n individual; all ante-mortem trauma or pathology, < ~ n all d peri-morten~trauma. /-/,yllte 6.1 A torens~cc,iw l a d out rlll,lt~~~lllc'lll~ 6.2.2 The biological profile The second phase of the analysis is concerned ~ v i t hcreating a basic biologic-ill profile of the individual skeleton: determining sex, ancestry (if relevant t o the identification of individuals for repatriation and/or judicial needs), age, and stature during life. It is not the intention to repeat what is widely understood a b o u t basic anthropological methods but t o stress issues of key concern in forensic applications. It is, however, necessary t o review 'ispects of methodology that arc generalty not well reviewed in standard osteological texts. 6.2.2.1 Sex Sex ( n o t gender) must be assessed first, as it will prescribe the methods used for tlie estimation of both age and stature. When a biological anthropologist examines a skelesex, not his o r her gender. Sex is a lliological tun, lietshe is determining the individ~~al's consequence of chromosomal inlieritnncc; gender is a social construct hased on how the individual self-identified, was cl~lssifiedby histher culture, and behaved during life. While gender mo! be inferred from the context in which the skeleton appears (clothing, personal cttccts, ctc.), the anthropologist needs t o assess the skeleton independently of these features first to determine biological sex. Method\ for determining sex are discussed in standard texts s~iclias White (2000), and France ( 1 9 9 8 ) . a n d critically reviewed by many others such a s Mays and Cox (2000).Sex difterences niay be observed in the hum'ln skeleton after the onset of puberty nnd n o attempt S I I O L I I ~ be rn~~cie t o appraise the sex of :In individual whose innominate m , of an individual w h o displays a complete lack is not fully fused a t the a c c t a l > ~ ~ l u nor of epiphyseal ~ ~ n i oofnthe long hones. D N A can he used t o determine the sex of infants and j~ivenilcs.Caution ~lluctbe applied when transferring anthropolosical techniques from o n e population t o the neut c~ntilthe anthropologist becomes familiar with the normal range of variation hct\vcen mules and females within any given population. I n certain populations, most notahly the United States, it is also possible t o assess sex osteometricnlly from the c r a i l i ~ ~ iby l l eniploying a discriminnnt Function. Several s not be notes of caution are warranted. The f e a t ~ ~ r ~e ~s p p l i c a btloe US p o p ~ ~ l n t i o nliiay appropriate i t applied t o the remains of individu:lls derived from other geographic regions. For csample, the crania of Japanefe rnnles are extremely gracile hy American s Sledzik and Ousley 1 9 9 1 j and may be classified incorrectl~,usins standards ( R ~ s 1983; LJS metric and visual cues. ( A more reliable, i t sul~tle,indicator in these cases is the i l present in Japi~ncsc~ n ~ l eBass s , 1983.) In another ex~imple, extenclcd s ~ i p r a m e a t ~crest if the population t o which nn individual belongs is unknown, osteon~etricallybased discriminant functions ni:l\ clnssify tlie individual incorrectly because ancestry cannot be taken into coiisider,itio~~. Newer forni~ilae(e.g. FOKDISC 2.0; Ousley and J a n t z 1996) calculated from cr,lnial measurements obtained from a broad geographic sample , ~ l l o wone to i n p ~ i t1' single series uf Ineasureinents and receive a n output providing inform,~tionof both sex and ancestry simultaneuusly. However, caution is warranted in ~ipplyingthis method as well; like all statistical packages, the program will always cl.icsify the data input into the categories nv:~il:lblet o it - and only illto those categories k n o ~ v nt o it. It n i ~ ~ also s t he noted that, ns ~ v i t hmorphological assessment, metric methods ,Ire ~ l l s opopulation specific a n d cannot be applied indiscriminately. Onl). i t the pelvis ( o r even a single innominate o r pubic bone) and crnniuin are not available, should tlie antliropulogist turn to other skeletal elements t o determine sex. While osteometric standards for many postcranial eleinents exist a n d provide a reasonable degree of :1ccur:1cy (most classify a n individual correctly approximately 8 0 per cent of the time), their reliability is less than that of the pelvis and cr:lnium. Many of these formulae are hased o n measurement of bony landinarks that correl,lte strongly t o size differences hetween males and females, such 11s femoral o r hunleri1l head diaiiieter. They ,Ire, however, like all s t ~ ~ d i in e s hu~n'lnvariation, population specific. So the scinie precautions about cross-population npplicahility apply as regarding tlie t i o n always be done non-metric observations discussed above. Sex d e t e r ~ t ~ i ~ ~ ashould using a s many features of the skeleton a s possible. No single indicator is a s accurate a s a n assessment of the whole. T h e estimation of ancestry, o r t h e biological a n d geographic origins of t h e individual according t o their genetic history is a n integral part of the biological profile. While most medico-legal agencies a s k for a d e t e r ~ n i n a t i o no t t h e rilcc of t h e individual remains in order t o search ~llissiilgpersons files, it is n o t possible t o precisely correlate social rile-e a n d biogeographic ancestry. T h e former is primarily based on external differences perceived t o exist ainong popiilations o r ethnic groups ( a n d definitions niay differ greatly f r o m country t o c o u n t r y ) a s well a s individual self-identification during life. T h e latter is biised o n population hiological variability a s inaintaincd via genetic drift a n d marriage patterns a n d preferences ( n o n - r a n d o m mating). H u m a n variation results f r o m relative genetic isolation (endogamy) of p o p i ~ l a t i o n sfor long periods o t time, which accentuated particular characteristics in each population. While solne variability is adaptively based, m ~ ~ c of l i it is simply the result of t h e perpetiiation of' particular m o r p h o l o g y d u e t o I>reeding within a restricted area. T h i s is all relative, a s people living in t h e centrc of a population area will most reseinhle the 'norm' for t h a t population, while people o n t h e etlgcs of t h e populatioii will s h a r e characteristics a n d 'blend' with those of o t h e r adjacent populations. Recause m o r e vari:~tion exists z~~ithill s o m e popul'ltioiis t h a n exists l ~ e t z i ~ e them, ~ r n race a s a biological concept is untenable. T h e al~ilityof most forensic anthropologists in t h e USA t o e s t i ~ n f i t ancestry e so that it does, in fact, correspond with a sociiil race category is n o mystery (Sauer 1 9 9 2 ) . M o s t o t the tormulac a n d morphological criteria for separating 'whites' troni 'blacks' were established based o n collections of individuals of k n o w n 'race' w h o h a d d o n a t e d their bodies t o science, such a s those t h a t m a k e u p t h e Terry C o l l e c t i o ~ ia t t h e N a t i o n a l M u s e u m of N a t u r a l History a t t h e Smithsonian Institution. In o t h e r w o r d s , t h e individual cadavers w e r e assessed for sex a n d race while they \yere still fleshed b?- an anthropologist w h o assigned a social race category t o then?. Then, when anthropologists later n ~ e a s u r e dtlie remains in these collections t o derive f o r i n i ~ l a efor estimating race, their race categories were those designated by someoile w h o h a d already established their 'social' rflce based o n their external appearance. It is n o \yonder, then, t h a t these skeletally based e s t i n ~ a t e soften a p p e a r t o coincide with socially prescribed categories t h a t are, however, biologically meaningless. ,An anthropologist is able, nonetheless, t o be fairly accurate in estimating the ancestry o t individuals. Ancestry is most :lccurately assessed through t h r observation of m o r p h o logical a n d osteometric craniofacial variation (see, for example, [;ill 1 9 9 8 ; Howclls 19-3. 1 9 8 9 ) . Because, howe\,er, tlie majority of foreiisically-oriei~tedcraniofacial studies have hcen based o n 5kelctons of k n o w n s o c i ~ ~race l categories, o u r applied categories of ancestry a r e themselves rather limited ( f o r e x a m p l e , African, E u r o p e a n , Native American, ~ l n dAsian). Few crania are likely t o exhibit all t h e cl~aracteristicstypicnl of a given population; t h e anthropologist iiiakes these determinations based o n t h e presence of 11 majority of characteristics t h a t typity a pilrticiilar ancestral population. In tlie event t h a t character states a r e tl-illy mixed, t h e anthropologist s l ~ o u l dindicate t h a t the ancestry of the individual is mixed. A craniuin t h a t displays a n eqi~i\,alenceof European a n d Native Amel-icnn features s h o ~ i l dsimply he reported a s such, with 110 concession to a social r x e category as this can be very misleading. For esamplr, the skeleton of ,I !.ouug lvonlan whose cranium displayed such a mix of features was cxamineci; when identified, it hecame known thnt her father was 'white' hut her mother \vns n Blnckfoot Indian. In ;lnother incident, the cranium of a young niale clisplayed ,I similnr suite of kutures; when identified, the individual urns :I migrant farm worker of h l c i c a n ancestry. His social race category w o t ~ l dhave been 'Hispanic' o r 'Latino,' liut such n c ~ t e g o r yis really n linguistic grouping fraught with implicatior~sthat have n o biological population hnsis. A word ot turther caution is appropriate here. In many international investigations of h u r n a l ~rights ; ~ h ~ ~ sethnic c c , cleansing a n d gcnocidc. the assessment of ancestry c:ln he highly inflnm~~i:~tory. These situations are created when one group of people accentuate tlic dittcreuces (religious, ethnic, cultural, historical, visu:ll. etc.) between themselves and nothe her group. While this process may he initiated by political leaders \vith a nationalistic n g e n d ~ the , idea quickly spreads via propaganda throughout the pop~il:ltionnt large. 'l'he consequences arc readily apparent throughout the twentieth century - the (alleged) Ar~neninngenocide, the Holocaust, the Rwandan gcnocide, the war in the formcr Yugoslavia, etc. Therefore, it is necessary for the anthropologist t o consider it-hether ;lssessment of ancestry is truly necessary t o either the identification process o r the j~tdici:ll process. It it is not, it is recommended thnt ancestry Assessment should not be undertaken The potential ahility of a ' s ~ i ~ n t i sto t ' differentiate individuals o n the hasis o t their cranial shape in:ly he adding fuel to the fire by a p p e ~ r i n g t o legiti~iiizcthe very pr:lcticcs the conseqLrences of which they are investigating. Estimating the ,Ige ut death from the human skeleton ic argi~ahlythe most important and the most difficult portion of the analysis (for a critical review of this subject, see C o x 1000). Thc in~portanccof age estim:~tionis that it allows the investigator to nnrrow the search t h r o ~ ~ grnissiny h person's records (for all females, for example) to a specific rclnge (c.g. female5 bet\vecn the ages of 2 5 and 3.5 years). Despite the methodological problems i n h c r e ~ with ~ t av,~ilabletechniques, the anthropologist must always provide a range of 3gc, ;IS none of the techniques for estiniation can account for variation in growth ~ l n dd e g ~ n e r ~ ~ t changes ive across sex a n d population differences (see, for cr:lniple, P,rl.ric ct 2000; Si~nmollse t irl. 1999). With experience, an anthropologist \ \ i l l be able to provide nn ,lge range estirnate with reasonable accuracy, but not wit11 precision (he o r she \\.ill Iie\er report that 'the individual was 22 years of age' but rather t h ~ 'the t i~~dividnnl WAS 10-25 years ot age'). The anthropologist sho~ildalways examine ~111nv:lilal~leskeletal markers of Age, and not rely o n 3 single agc indic,~tor.The final age esrimclte must be brolld a n d inclusive; it should incorporilte the age ranges for .1I1 indicators. For ex;lmple: the epiphyscnl ~ l g cfor a skeleton is 2 17 a n d i 30 years; the puhic symphysis provides 3 range of 19-34 years; the auricul~lrsurface of the ilium suggests 30-24 yeL1rs;and the sternal rib morphology indicates 24-28 years (see Figure 6.2). A n Llge estimate ot 20-30 y e ~ r smight be rather broad, hut not inappropri~lte.X l ~ ~ r g i on ts error s h o ~ ~alw~lys ld be stated. It should he rerneolbered that most ageing methods (juvenile and adult) available to anthropologists are also /)op~rl,ltion spec-ific.and they may only be applied t o other populations with caution. In juveniles, nutrition. diicasc, 'lltitude, : ~ n dother environ~ncntalfactor:, have heen demonstrated t o affect both growth and maturation rates (Frisancho 1993; Scheuer and Black 2000). Skeletal and dental ages are not always in agreement within the sanle individual (Ubelaker 1987); as dental development appears t o be less susceptible to periodic environmental stressors, dental estinlates should he regarded as the more reliable age indicator. If the individual suffered from nutritional stress o r ~ ~ skeletal disease, it is not L I ~ L I S L Ifor growth t o be retarded by several Figrrrc,0.2 T h e right fourth sternal rih used t o n ~ o n t h sor years relative t o dental estimate ,1ge in a forensic case maturation. Lkntal development in sub-adults is the most important means of age estimation. Both the deciduous and permanent dentition develop t h r o ~ ~ g h tvell-defined stages of formation and eruption (Garn et al. 1 9 5 9 ) . The best means of evaluating clental age is radiographic, although a visual inspection is sometimes adequate tor a rough estimate. Standards for dental eruption exist for several populations, but the variahilitp should not he ~~nderestirn:ited. It should be ren~en~bereci that the sequence o t development and eruption may be regarded as more fixed than the tinling of eruption. 6.2.2.4 Stature If the remains contain any complete long bones, stature estimation can be accomplished for USA and some other populations \vith both ease and accuracy. It must he remembered, however, that as discussed above for other aspects of the biological profile, stature formulae are population specific t o geographic area and time period. Nutrition, disease, altitude, and other cnviron~nentalfactors all affect both growth rate a n d trajectory, and hence they impact upon population target height (and average height). Most stature formulae art. based on the assumption that a long bone is proportionally related t o the overall stature of the individual. Stature estimation can he quite accurate (if not precise) tvhen the individual is compared t o a population ~ v i t hestablished growth curves, known average statures and stature distributions, a n d one which is contemporary with the individual. This is particularly important since secular trends regarding proportionality and stature estimation factor into the accuracy of prediction. Jantz and Meadows (199.5) a n d Simmons et a/.( 1990) both discuss the secular trends in femur: tibia ratio over time in the USA, based on data from the Terry and UT-K collections. Tibia length is seen t o have increased over the past 50-60 years, and now accounts, more for total stature than does femur length. Similar trends have heen observed in stature a n d body proportions a m o n g the japanese ( O h y a n ~ act al. 1 9 8 7 ) and in other populations. Obviously, this renders the accuracy of stature estimates for recent leg bones, when using the Trotter and Gleser ( 1952) formulae, subject to question. If an individual in the USA died prior t o the 1960s, for example, the Trotter and Gleser f o r m ~ ~ l are a e probably the appropriate ones to use; if 011 the other hand, the individual died within the past 2 0 years, then Ousley's (199.5) equations based on a modern forensic .;;lnlpIe a r e probably better. Certainly the original ohscrver's Ineasurenients must be accurate a n d rcplicahle for any stature esrimation method t o be reliable. Jantz ct '71. ( 1994) recently pointed o u t discrepancies in Trotter's measurenlents of the tibia a s used i l l her 1952 a n d 1958 forniulae (Trotter ancl Glaser 19.58).These articles rcconimend t h ~ ift the 1952 f 0 ) . t i ~ ~ t lisi zused, ~ the n ~ a x i m u ~tibial n length roithoz4t the nz~lleolus should 1)e measured, if the 19 i 8 formtllae is used, the ~ n a u i m u mtibial length itz~l~iditzg thc t71~711~o114s shollld be ~ i ~ e a s u r e dFurtherniore, . they recommend that the 1958 t o r ~ l i l ~ l abe e avoided, a s Trotter's original nlz:isurenients c a n n o t be assessed for accur;icy. Estimating stature from fragmentary long bones (i.e. Steele 1 9 7 0 ) presents some unique problerns concerning rhe ability t o replicate measurements. T h e Steele f o r ~ n u l a r covered 211 long bones, hut the landmarks were particularly difficult t o locate, a n d hcncz measllrement reliability a n d repeatability were comprorniscd. Simrrlons ct '11. ( 1 9 9 0 ) attempted a revision of the Steele method ( f o r the femur only) hy proposing m o r e clear-ly defined skelctal larldmarks. Their results actually bettered Steele's, albeit t o a small degree. hut still require the esti~nationof bone length first, prior t o the estimatiori ot stature. This conipouiids measurement error, ns t w o formulae are used, both with standard errors o t estinlated. With both the Steelc a n d Simmons, et (11. formulae, however, the estimates are quite broad, and lnay serve as e x ~ l u s i o n ~ ~evidence ry hut only tor professional hnsketball playcrs ancl jockeys! As in estimating agc, it is vital t o provide 3 s t ~ t u r erange, not a precise e s t i n ~ a t rof all individual's height. S o ~ n individuals e le.g. O ~ l s l e y199Sj ridvocate using t w o standard deviations f o r cstiin,lring stature, thus insuring t h ~ the t individual's height in lift. will fall within the low a n d high ends of the range. While this may he the statistically correct procedure, niost stature estimates using one s t a ~ i d ~ idevi'ltion rd usl~allyestimate a n individual's height with exicllcnt I-esulrs. It should also hc noted that while stature estimation is a nccrssary portron of the biologicnl profile of' a n individual, a n d is often i~setulin single case-\vork in the USA, it is not n particillarly dependable criterion tor icientiticntion i l l un international setting (Icolnar 2 0 0 3 ) . In the USA the s t : ~ r u r e estimate may help t o elimin:ite a range of missing persons (e.g. those under 1 7 0 c m and o\:er 180cn1 in height) from the pool of possible victinls. However, in places such a s R w a n d a o r Bosl~inwhere a n t e - ~ i i o r t e mstature ~ u e a s u r e l n e n t sa r e not rourinely recorded (c.g. n o rliedical o r driver's license staturcs available), the information is of equivocal value. Relatives may be able t o cstimate the stature of a missing person, but :is > c t IIO stdl1dards exist tor correlating 'recollected stature' with estim,~tedskeletal s t ~ i t u r c .I n addition. applying any stature formulae consistently t o the Srebrenica population revealed that the vast majority of tlic 4,500 individuals exhumed were ot siniilar stature, hetween 170-1 SOcl11. 6.2.3 Trazrma, cazise r111d manrter of death T h e next pli;ise o t the ~ l l a l y s i si b identifying any evidence of ante-rnortern tl-;1ulna o r pathology o n the skeleton that may aid in the identification of the i n d i v i d ~ ~ aand l , the final phase is idelltifying ally indications of peri-mortem t r a u m a that )nay indicate how the individu:ll died. With the latter, the alithropologist must be able t o distinguish pcri- From post-niorteni trauma t o bone. As with t h r taphonomic inventol-y discussed ribovc, it is ~ r c c o ~ n m e n d ethat d thc Inhoratory protocols contain 3 coniprehcnsive listing of potential ante-mortem conditions and peri-niorte~ntraunia that is anticipated t o he encountered. This allows the conditions t o be coded for ease of data retrieval for both identification and judicial proceedings, respectively. 6.2..;.1 Ante-nzortem trauma and pathology The forensic anthropologist must assess the skeleton for congenital abnormalities or any signs o f disease or trauma that the individual suffered during life (Figure 6.3). Mainly, the anthropologist is searching for evidence of diseases that alter bone (hypertrophy or atrophy) on local o r systemic levels. In both cases, certain neoplastic, infectious, and metabolic diseases can he the causal agents. In the case of trauma, the anthropologist is searching for evidence of past injury t o bones or joints (fractures, dislocations, etc.), which may be healed o r active. This also applies t o the dentition for which disease a s well as its treatment (dental restorations, crowns, etc.) should be recorded. Ante-mortem and post-morte~n radiographic comparison is the best means of positive identiFig~lrc,6 . i h hilatcrnl congenital nhnormnlity o f the fication, whether dental or ~ n e d i cuncifor~n ~l in ;I torc~lsiccase skeletal. If radiographs are not availablc for coniparison, only a presumptive identification can I>emade o n the basis of injury ( o r diseasc) location and type. If present, prosthetic implants are another key factor in identification as most produced within recent dccades contain maker's marks as well as serial numbers that allow them t o be traced to the man~ifacturcrand/or the hospital where the surgical procedure was performed (Ubclaker , ~ n dJncobs 199.5). X c<~reful evaluation of all peri-inortern trauma t o the skeleton is critical to a forens~c anthropology examination. Signs of injury may not only suggest manner and cause of death (traditi(~)nally the real111of the forensic pathologist), but they may also provide insight into the treatment of the hody around the time of death, and its disposal. Perirnortenl injuries arc those that occur around the time of death. As hone retains its organic component for some time after death (though this is variable dependent upon taphononiic factors), it is extreniely difficult to differentiate hetween danlage inflicted t o living hone, or to hone shortly after death. This can, however, be undertaken using scanning electron microscopy (when it can be cietected after about 12 hours -Jones and Boyde 1993).The first change that can he detected macroscopically is often a localized periosteal reaction. X forensic anthropologist is generally concerned ~ v i t l ithree types of peri-mortem t r a u m a : blunt force, s h a r p force, rind proiectile (gunshot a n d fragmentation injuries, e.g. Figure 6 . 4 ) . Xs in all things, a great deal of experience is necessary t o evaluate each of these types with authority. Unfortunately, given t h e events of t h e past decade in R w a n d a , Bosnia, Kosovo, Sri Lanka, Indonesia a n d o t h e r places, these types of injuries a r e hequently being seen or1 :I large scale by forensic anthropologists working ~l organisations a n d w a r crimes tribunals. T h e t o r such org:inisations :is h ~ i ~ l l : lrights liternture o n b l ~ ~ force, nt s h a r p force, ,lnd projectile t r a u m a t o t h e skeleton is still in e so r k by M a p l e s ( 1 9 9 8 ) 011 t r a u m a analysis in general, Smith its inf"inc\, but i ~ ~ c l u d w c.t '71. ( 1987) o n gunshots t o the cranium, S a ~ ~( e1984) r o n blunt a n d s h a r p torce trauma, C;allo\v~~!.(2OOO) o n blunt force t r a u m a , a n d I\crlc)- ( 1 9 7 8 ) o n battered-infant syiid r o m e . Surgical t r a u ~ n am a y also be recorded as peri-mortein, if t h e inclividual did n o t survive the procedure long enough tor skelet:~l healing t o be eviclent (Figure 6.4). O n e of the m o s t c h ~ l l l e n g i nissues ~ in investigations of genocide a n d crimes a g i ~ i n s t hum:lnity is that i)t victin~identitication. Iclentification has critical meaning for survivors, tor c o u r t s , a n d t o thc expert. F o r t h e latter, t h e status of a n identification c a n be expressecl as tent:~tivt', p r e s ~ ~ m p t i v oe ,r positive, o n the hnsis of h o w the identification nil1 st,inci up t o objective criteria and second o p i n i o ~ scrutiny. i T h e majority of iden- tificntions done both in the USA a n d abroad are presumptive identifications, based o n good faith ~lcceptanceof the dead person's identity. This is generally not questioned. In honlicides ilnd insurance cases, the identifications are generally held t o a higher standard and must therefore be positive. The identification of victims in mass tatality e\.ents, war, ethnic cleansing, genocide, etc. is often seen as 3 more complicated issue. Identifications in the US are the result of predominantly circumsta~ltialand visual lncnns. These consist of recognition of facial features, o r based o n circumstantial evidence such ns personal effects, documents associated with the body, or ~~nchallenged testimony t o the effect that a person is w h o slhe is presumed t o he. Technically, these are presumptive means of identifications and are common practice when there are n o questionable circumstances t h ~ i twould call the identification into question. For example, 3 body wallet in the individual's is removed from the wreckage of a car after ,In accident. 7171~e trouser pocket indicates n white male, aged 35, 5' 10" in height by the name of ,lohn Smith. The cLlrfrom which the hody comes w:ls registered t o a John Smith. The body conforms reasonably well t o that of 3 male about 5' 10" in height in his thirties. The body is therefore identified as John Smith. As long as John Smith does n o t appear, and assuming that the tnmily, insurance company, or others d o not dispute the identification, then the identification is accepted. In the vast majority of cases such as this one, an anthropologist , ~ n d / o rodontologist is not involved in examination of the re~iiains. Deviations from this practice in the USA occur when: ( 1 ) there is n o means of visual identification possible; e.g. bodies that are disfigured, decomposed o r skeletonized; ( 2 )in all cases of homicides; (3)when there are perceived questionable circun~stances surrounding the death; a n d (4) in the event of n mass fatality situation (c.g. a plane crash, bombing, fire). It is a t this point that objective, scientific means of identification are pi~rsuedI!,. way of fingerprints, dental identification (Figure 6.5) n~edicalradiogr,lphs, or genetic ( D N A ) identifications. \Were none nre initially available, the stage is set for methodologies that will document lead-generating information, and it is here that diaciplines like nnthropology rnlly become in\rolved. As anyone w h o has ever F I ~ I ( 2I. 5~ The mnxillnry ( 2 )and mandibular (1)) dentition call aid identification whcre dental records exist worked on a Inass fatality incident knows, there is trenieudous pressure to insure the rapid identification of all victims. Sonletimes this is due to political pressure. Primarily, however, such pressure comes from the families of victims. They desire the return of h due speed so that the death c:in be authenticated and their loved ones' r e n ~ a i n s~ . i r all the more r i t ~ ~ a l i z eand d formalized n ~ o ~ ~ r n period i n g can begin (and that probate and other fiuiincial niatters can he settled). In the USA and developed countries with relati\.el!~sophisticated infrnstruct~ires,most victims can he idvntified with relative rapidity o ~ v i n gt o the uhicluitous presence of, and ease of access to, independent docun~entationsuch as medical and dental records, or fingerprints. This is p a r t i c ~ ~ l a r l y so tor cert,~insegments of society (e.g. military and other employees previo~islyscreened tor security clenrances, etc.). DNA is utilized more aiid more t o effect such identifications. W h a t is perhaps of' most interest in the context of this discussion, is that the issue of positi\,e identitication becomes paramount in Inass fatality events. This is for two reasons. First, multiple victims are involved for \vhom there is no reliable manifest (c.g. passenger a n d crew manifest, documentation of employees present in a building on ;I given day, etc.). Second, there is often fragmentation of the victirns - o r delay in recovery of ~.emainswith s u h s e q ~ i e n decomposition. t In either case, recognition of iiidivid~~als and ready nssociatioil oi all parts o t an individual obstructs the identification process. There is extreme relucta~lcein US mass fatality events t o issue a death certificate reliant upon 'circurnstnntial', o r p r c s ~ ~ m p t i videntitications e (altho~rghthe events o t I 1 September LO0 I werc an esccption, although all identifications are being confirn~cdhy DNA). Experience has shown that even in passenger lnanifests there are falsities, hence, plane tickets and even peraonal identifying doc~iinentsfound o n the body are susceptil>let o cl~~estion and a death certificate may not he issued. There Lire of course, exceptioils, hut these d o not come cluickly t o the certifying iiuthorities. Such a n example is a pl:ine crash with one individual t o be identified. No dentition for this tnn3le was recovered, she had no tattoos, she I i ~ dnever heen fingerprinted, and the family could not provide any ante-mortem radiographs for comparison to the hody in cluestion. The biological profile for the lmdy matched and the woman was wenring copious amounts of gold and diamond jewelry o n every appendage, which the family ie\\.eler h a d designed for her alone - and kept photographic records o t each piece. Debpire this, the ,2lediciil Exa~niiierwas reluctant t o dcclare that thc female body was passenger X, because there \vns n o llleaiis of positive identification. This was despite the unlikely possibility that this woinan had boarded the plane and had elected t o voluntarily cxchangc every piece o f her highly ~ l i i i q ~ ai en d expensive . as she was thc only i in identified jewelry in mid-flight with another w o ~ n a n Ultimately, (by positive means) individual recovered from the complement of victims, she was presumptively identifi ed on the basis of the biological profile and her documented i~niclue personal effects alone. A death certiticate was iiltimately issued for her as it had been for all other positively identified passengers. T h e families and agencies involvcd in mass fatalities attain resolution t o the deaths via identification and are able, with the aid of the existing infrastructure of v a r i o ~ ~ s social serviccs, the go\,ernment, religious and c u l t ~ ~ r institutions al to resume their dayto-day li1.e~.Things will never be the same for the family memhet-s, but thc reality of the dcath as attested hy positi\.e identification is not in doubt and is rarely questioned. X Y I F - I R O P O I OCrY I N -\ I - O l < T h 5 1 ( ( ONTFXT 6.7.4.2 Idcntrficatrons uftcr tuar, genocide and crirnes ag~zinst I~tlnrnnrty People's attitudes toward the exhumation and identification process are varied and, to a certain extent controlled by the political climate. For example, the identification of people killed in 1992-95 in Bosnia is a complex process that has ditfcrent meanings for different people. For some relatives of the missing, it is a relief, providing the end of i~nccrtaintyregarding the fate of their loved ones. For others, it is unciesirable, forcing them t o confront the death of an individual for whom they held o ~hope ~ t of life. Several families of Greek Cypriot and Greek victims of the 1974 conflict h~ivelong been activists lobbying for identification of the missing. O n the personal level, differences in people's acceptance of the exhumation and identification process often reflect the political perspective because it gives them hope, however false, that thcir loved one is alive. Some people want t o know if their lovcd one is dead and t o he able t o hury them. They seek resolution t o their questions so that they can move on with their lives. They will accept the identification. Some survivors are s o desperate for resolution to their pain and uncertainty that they have tried t o persuade experts t o attribute an identification for which there is no scientific basis. The establishment of the identification of the victim is most crucial hoth to proving charges of ho~nicideand directing the inquiry into the cause and manner of death, leading t o an identification of tlie perpetrator (Geherth 1995).While this dictum forms the basis of localized and individual homicide investigations within most developed countries, there is frequently less emphasis on personal identification than one would expect from the prosecutors in current 111ternation:llCriminal Tribunal investigations of deaths related t o war crimes and genocide (Haglund 2002). For their purposes, it is often considered sufficient to 'categorically' identify tlie victims by their ethnicity or their religion, whether they were men, wonien or children, civilians or combatants, o r soldiers incapacitated by bindings o r hlindtolds. This does not imply that positive personal identification w o ~ i l dnot lend deeper support t o indictments o r to the international criminal trihunal's investigations. Nor does it imply that personnel connected with the tribunals d o not feel that person;il positive identification is important t o the tnrnilies of tlie victims. It is siniply that a pursuit of this level of identification has not been a primary issue t o the prosecution. It is arguable that the changing nature of international forensic projects (including the growing sophistication of the families of the missing and their awareness of the possibility of identification through DNA, etc.) necessitates tlie inclusion o t a provision for the identification of the victin~sfor humanitarian reasons. This provision will, o i course, extend not only the budget, hut the duratio~iof cases as wcll as the nuniber nnd expertise of personnel required. This is true regardless o f whether presumptive o r positive identifications are sought. Personnel, expertise and resources are needed to conduct interviews gathering anteniortem intormation ahout the missing, collect DNA samples from the relatives, and compile dat;ihases. C:ornmunity education is nlso a necessdry component of such work in order t o educate the families of the nlissing a b o ~ the ~ t process of identification and the length o t time it is projected t o tuke. The issue of 'capacity building' within the local, established forensic com~llunityalso bears consideration wl~ereverpractical. 6.3 Laboratory resourccs LJndertaking :~nalysisof h u m a n remains requires a secure e x a ~ n i n a t i o nand storage area. A secure area means that only authorized people have access to the area, room o r building, ivhich is kept locked and/or g ~ ~ a r d eatd all times. A detailed inventory of what evidence enters the facility is kept and tlie chain of custody is maintained. The safety of laboratory personnel is of paranioulit concern and all individuals should use universal prec~lutiotiswhen dealing with human remains. As a minirnuni, e\.eryone should wear latex examination gloves if dealing with fleshed remains. I'rotectivc clothing a n d masks s l i o ~ ~ be l d worn when necessary. All personnel w h o are certified to work in the lahoratory should also have been vaccinated for tetanus a n d hepatitis 8. A first nid kit s h o ~ i l dbe available and all personnel aware of its location and its contents. Contents should inventoried a n d re-supplied regularly. All personnel should be knowledgeable about hiohaz..;lrds and necessary safety measures (Galloway and Snodgrass 1998) a n d briefed o n any unique potential hazards relative t o a particular project. T h e l a l x ~ r a r o rshould ~ ideally have running water, electricity and an examination tahle large enough t o place :In adult huniali skeleton in the nnatomicr~lposition (see also Table h . 1 ). It the reni~linsare skeletal, tlie table or other examination surface should be padded (foam rubber o r b u b b l e - ~ , r n pwork well) so that the bones are not damaged by contact with a hurci surface. It the remains contain soft tissue, then the table should he met.;ll (plastidfiberglass trays are an option) and the availability of water becomes essential. When handling skeletal rcniains, the anthropologist must ensure that the bones are clean prior t o ex,lniination in order t o observe morphological features, analyze trauma o r pathological conditions, conduct osteometric analyses, and facilitate storage. T o relilove loose dry extr.;~neousmaterial, it is best to simply brush hones with a soft bristled l ~ r u s hot natural o r nylon fibre. If the bones arc Illore encrusted, washing them in plain warcr with the aid of a soft brush may also be appropriate. Bones s h o ~ ~ l d never be allo\ved t o 'soak' in water. Care must he taken during the drying process. Bones must not he allowed t o dry t o o c l ~ ~ i c kand l ~ , exposure t o heat, direct sun, or blowing air should be avoided as these may cause surface fissuring and breakage. X ~ i r y i n gruck of wire or plastic mesh that allows air t o reach all surfaces of tlie w c t bones e\.enly is ideal for this purpose and easily constructed. When a h s o l ~ ~ t cessential ly t o deflesh selected elements (i.e. age, sex, etc. cannot be determined without doing so), it m:ly be necess,ir>-t o remove certain clements (pubic sy~nphyses,sternal rib ends, medial cia\-icles, etc.) from the body and remove soft tissue from then1 prior to e x a n ~ i nation for determining the individual's biological profile. Surgical saws, either electric o r Ihand-po\vered, a n d clippers are necessary t o this task and dissecting equipment riiay he needed to expose the hony landmarks prior t o their removal. Detleshing remains, whether in whole o r in part, is an integral part of lahoratory analysis. R e ~ n o v a lof tissue from r e ~ n a i n sbrings up several issues to he considered. It is not uncommon tli~ltremains will not he identified for a long period following their exnmination. Removed soft tissue should he considered a part of the renlains and thus should not be simply discarded. Unfortunately, inl like hones, which arc relatively ~. simple t o store, soft tissue decomposes in the absence of preservatives or proper refrigeration. When faced ~vitlithis challenge, alternatives need t o be explored. An often ~ltilisedmeasure is to bury the remains ~ 1as storage measure. It is necessary that burial occurs in an identified grave fro111 vvhich rcrn;lins c,ln later he retrieved. While this XNTHROI'OL OGY IN r\ F O R 1 NSIC ( ONTFXT Trlble 6. I Basic laboratory equipment for a n t h r o p o l o g i ~ ~an'llysis ~l Secure storage area Labor'ltorj protocols Record~ngform5 (p'lper o r conip~~terired) Latex exami~iationgloves Faceleye shields Cloth or disposnhle protective clorlii~ig E x n n ~ i n ~ t i otable5 n Evidence hags and boxes hletal tags C:;~selabelsItag5 (paper or plastic) Spreading calipers Sliding c,~lipers Osteolnerric hoard Comparative age estim;~tioncasts (Rib. Puhic Symphysis males and females, a n d epiphyseal union) Study shrleto~i(both articulntedlhanging and hoxrd) - Selected referencc texts Sand box C;I~ies(both water soluble and acetone soluble) and solvent5 Basic pllotographic equipment (S1.R 3Smn1. d i g i t ~ and l vidco cameras) Ilarkroom equipment Photo stand, tripod and ladder Measuring scales Dissecting microscope Thin sect1011equipment X-r;iy machine and radiographic developing ecluip~nent Computers. scanners, printers, and various software, programs such as FORDLSC 2.0 does n o t forestall nature taking its course as far a s decomposition is concerned, it does reduce potential liability from having discarded the iiiaterial a n d m a y satisfy religious custorns (e.g. Islam, Judaism) t h a t prescribe t h e burial of all body parts. The ideal w a y t o deflesh is by use of :I derinestid beetle colony in which beetles eat a w a y the flesh w i t h o u t damaging t h e skeletal eleriients. However, t h e beetles consutne the flesh a t a rate t h a t is usually t o o slow for most forensic cases, a n d relatively tew laboratory facilities a r e able t o nluintain these insects ( a colony must have a c o n s t a n t 'food' source in order t o perpetuate itself). T h u s , in order t o expedite the cleaning of remains, as m u c h excess soft tissue as possible should be first removed, taking c a r e n o t t o use sharp-edged it-nplements n e a r t h e borie surface itself ( m a r k s left might ;\NTHKOI'OI.O(J~' IN X FORENSIC: (:ONTEXT potentially he c o n f ~ ~ s ewith d peri-mortem i n j ~ ~ r i e sFollowing ). this, the skeletal elements s h o ~ ~he l d simmered, at a low boil in n weak solution of water and a commercinl enzyme detergent (Fenton ct ~ 7 1 .2003). Adding potassium hydroxide t o this solution also acts as a catalyst t o the reaction, but vigilance is necessary t o ensure that the water level remclins high enough that the bones d o not char andlor that erosion and bleaching does not occur. X hot plate and com~nercialaluminum pots of considerable sire may he employed; this process should ideally be conducted under a fume hood. It is helpful that thc material be suspended in the water, rather than resting o n the pan s ~ ~ r f a cine order to eliminate the possibility of the contact surface of the bone with metal. A variety of materials may be used for this, including screening material (plastic o r metal) and mesh laundr). hags. With smc111 sections of bone, the same process can he accomplished more quickly Ivith the aid ot a microwavr oven. In either case, the hones should be removed from the Jvater a t frecluent intervals and additional loosened soft tissue removed until rhe process is complete. 6.4 Conclusion Forensic anthropology has expanded rapidly during the past decade. The case-load of forensic anthropologists has risen markedly in the United States (Reichs 1998) and hrgun t o develop in the UK. It has grown t o include fleshed and hurnt remains, led t o ;In increase in courtroom testimony regarding the interpretation of t r a ~ l m a as , well ts accidents and other issues to which our suhject as invol\.en~entin civil s ~ ~ iconcerning may he relevant (C;allon.ay 1999). The expertise of forensic anthropologists has also become integral ro investigations of genocide, war-crimes a n d crimes against humanity in man! p'lrts of the world. This ma!. be through the auspices of non-government human rights organizations, the United Nations and the L7d I)OCinternational criminal tribunals. With their participation in international projects thc role of the forensic anthropologist has also changed, necessitating changes in training and perspective relevant to this contest. The focus ot Forensic anthropology has shifted. From the creation of biological profiles providing leads to identification in individu'll cases, it is predominantly the interpretation ot peri-nlortem tr,Iuma, and the d e n ~ o n s t r ~ l t i oofn patterns in largescale events, that demonstrate criminal intent by the perpetrators of mass murder. The roles the forensic anthropologist is expected to fulfill have multiplied in international missions ,111d 3 new training, beyonci mere competence in technique, is needed tor those cntering the field. Tociny's forensic anthropologist must be expected ro be bvell versed in ,~nthropologicaltechniques, law, aspects of crime scene investigation, and issues invol\.ing human rights, a n d humanitari~lna n d diplomatic aspects of international projects. T o o few indi\.iduals hoping t o gain entry t o the field are aware of the complcs li,ltLlre of the work, its context, and the multiplicity of functions that they must fulfill. It is this that the providers of graduate a n d post-graduate education and continuing professional development must ~ d d r e s s . References Bass. W.hI. 19S.;. Hlrliz,ltr ()steology: L~rhor.,ltoryizird Fteld Manztnl, Columbia, hlO: hlisso~~ri ;\rcllaeologic~lIsociety. Bas\, W1.hZ. I99.i. 'Thc Occurrence o f I~lpanesrtrophy skulls t o r e ~ i r S~~i - I C I I CZ tLi :~3S. 800-SO.3. in the Unitcd Stares', /olrrni~lof Boles. T., Snow, C. a n d Stover, E. 1995. 'Forensic D N A testing on skeletal remains from mass graves: a pilot projcct from C ~ ~ a t e m n l n]orrrn,zl ', o f Forclrsic SCr~~l/i-c,s 40:3, 349-355. Urkic, H., Srriliovic, D., Kubat, M . and Petrovecki, V. 2000. 'Odonotological identification of human remains form mass graves in Croatia', Illtr~rrational,/ol(r7ra1of I,r,gul Mctiic-ilzc. 1 14, 19-22, Connor, M. and Scott, I). 200 1 . 'Paradigms n ~ i dperpetrators', Soc-iety for Historical A r c l ~ n e o l o ~ ) ~ - 1-6. .>.>:I, Cox, h l . 2000. 'Ageing h ~ ~ m askeletal n ~nnterial', in C o x , M. and Mays, S. (eds) Hrrnlair Osteology in i\rrhacolo,y!' a17d FO~L'IISIC . S C I ( ~ I I 1.01idc)n: C~, Greenwich htedical hledia Idtd, pp. 6 1-82. Fenton, T., Birkby, \Xi. ancl Cornelius, 1. 2003. 'A fast and safe nun-hleaching method for forensic skeletal preparation', ]uurrlul of Forc,irsir Sciences 48:2, 274-6. France, 1). 1998. 'Ohscrvational a n d metric analysis of sex in the skeleton' i l l lieichs. K. (ed.) t~orc~lrsicOstrolo:,.y: Atfz~uncrsirz the Irfe7rtific-Lztiorr of Hlrnzari RrrilL7irls,Springfield, 1L: Charles C . Thomas, pp. 163-186. Frisancho, R. 1993. H U ~ I I IAdiz[~tiztiorr ZI~ '71r11 A ~ ~ o n r ~ n o d i z t i All11 o n . Arbor, MI: linivcrsity of Xlichigan Press. C;alloway. A. (ed.) 1'199. Broken Bolrrs: Anthropologicnl Arrulysis of Bllrnt Force T r a u m a , Springtirld: Charles C. Thomas. Galloway, A. ( e d . ) 1 0 0 0 . Rrokrrr R o n ~ s :Anthri,pOlogical Alrulysis of Rlrrnt Fore-P Traulrln. Springticld, 11.: Charles C. Thomas. Galloway, A. a n d Snodgrass, ,J. 1998. 'Biological a n d chemical h a ~ a r d sof forensic skeletal 43:.5, 940-948. analysis', jozrrrr(z1 of F o r e n s i ~.SCIC~CPS Garn, S., Christabel, G., Rohmann, G . and Silvcrmaii. F. 1959. 'Variability of tooth formation'. ]olrrrr,rl of L>entul Krsc7~lri/~ 4.3, 243-2.58. C;cherth, V. J. lC)YS. Prilctit-irl Honricidr 11rr~cstigati~)rr: T(rctiis, Proc-edures, irntf Forc,r~sicT L ~ C ~ J I I ~New ~ L I York: C S , Elsevier. (Jill, G . W . 1998. 'Craniofacial criteria in the skeletal ,~ttrihutionof race', in Reichs, K. (ed.) Forer~siiOstcolog)', Springtield, 11.: (:harles S. Thomas, pp. 29.3-3 17. Flagl~ind,W.1). 1 0 0 2 . 'Recent mass graves, an introduction', in Haglund, W.1) a n d Sorg, hi. ( e d s ) ~ \ ~ / L J I Zin I I ~C' ~O S~ P I I ~xIrCi ~ / ~ o ~ ~ o hnfzeyt i:~ o d T , i ~ ( ~ ) rirlrd y , A r i - h a ~ ~ l ~PCI.S[I~C~~LJCS, ~i~al Roca liaton, FL: C R C I'ress, pp. 243-262. Haglund, W.I>. a n d Rodriguez, W.C. 1998. 'Forensic ; ~ n t h r o p o l o g y ' ,In Fierro, 1 k I a n d S c h a c h o ~ v a ,I. I..L. (eds) C A P H,7rriil)ook fi)r Postrlzorten~E s u i i ~ i r ~ a t i o of l i lrnici~ntifiecf K L ~ I I I Der~rloping ~~~S: ldclrtificution of Wcll-prcscrved. Di'ionrposcd, Blrrnrd, iznd Skrlrtoizizeti Rcii~~zins. Skokie, TI.: College of American Pathologists, 2nd edn, pp. 107-1.32. Ho\vells, W.W. 1973. (:rLr17ial \furiatiol~717 Mull: A Stlrdy by Mlrlti~,uriateAnal?,sis of Putterns of L)iffer~zn~.e urnorrg Krrcnt f l ~ r r n a i/'op~rl[ztiolls, ~ C:ambridge, MA: Papers of the Peabody M ~ ~ s e u rofn Archaeology and Ethnology, 1701. 79, Harv.ird [lniversity I'rcss. tHo\\~ells.W.W. 1989, Skull Shapes 'zi~tlt i ~ cM'rp: ~ Crar~iomc~tric .4nL~lyscs ill the Disprrsion of Motf~,rnHonro, C:amtlridge, MA: Papers of the Peahody hluseurn o t Archaeology a n d Ethnology, vol. 67, Hnrvard [Jniversity I'rrss. Hunter, I., Roberts, C1.A. a n d hlartin, A. 1996. Strrdrrs 117 C:rilnc: Ail l,ztrod~ritiorit o F o r ~ n s l i Arc-buc,olog),, London: Koutledge. j,intz, R., H u n t , I). a n d Mendo\vs, I.. 1994. 'MCiximum length o f the tillin: how did Trotter nieasLIrc it?', A I I I ~ Y ~ Cjo7frllLz/ IIII o f P h y s i ~ u A~rthropolo~qy l 93, ,515-528. Jantz. K . and hlcadows. I.. 199.5 ' S c c ~ ~ l a r c h a n gine long Iwne lengrh and proportion in [he Unitcd States, 1800- 1970', An~cric-ar~ j o l r r t ~ a lof Physic-a1 Ant/?rupology 1 10, 57-67, lone$, S.J. and Boyde, ,A. 1993. 'Histomorphonier~-yof Howship's lacunae formed in vivo and in vitro: depths ;ind volumes measured by scanning electron and confocal microscopy', U o i ~ c 1:3, 4 5 5 . 7 Kerley, F.. 1 978. 'The identification of battered-infant skeletons', Jourt2al of Forens~cSc~ences 23: 1, 16.3-168. Komar, D. 1 0 0 3 . 'Lesso~isfrom Srebrenica: tlie contributions and limitations of physical anthropology i11 identifying victims of war crimes',Jozirnnl of Forenszc Scicnccs 48:4,713-16. Maples, \V.R. 1998. 'Tr'lurnn Analysis by the Forensic Anthropologist' in Reichs, K. (cd.), Forct~src-Osteolog?', Springfield, 11,: C:harles S. Thonias, pp. 21 8-228. Mays, S. ant1 Cox, M.J. 2000. 'Sex determination in skeletal remains' in Cox, M. and Mays, S. (eds), H I I ~ I I JOstc~ology ~I 1i1 A~.chlz~oIogy '2nd torcnsic- Scicnc-e, London: C;reenwich Medical hledia I d , pp. 1 17-1.30. Oli!,ama. S., Hisanaga, A,, lnmasu, T., Yamatnoto, A,, Hirata, M. and Ishinishi, N. 1987. 'Some secular changes in hody height and proportion ofJapanese medical students', American lournal of Ph?'slc-,~lA t ~ t h r o p o l o ~73:2, y 179-1 84. O ~ ~ s l eS. y , 199.5. 'Should we estimate biological or forensic stature?',]ournnl of Forensic Scicnc-cs 40:5, 768-773. Ouslcy, S. and Jantz, R. 1996. FORDISC 2.0. Knoxville, TN: Forensic Anthropology Center, University of'Tennessee. Reichs, K. 1998. Forci~sic.Osteology: Adz~ar~ces in the ldet~tificatiot~ of H u n ? a t ~Renzuitzs. Springfield, IL: Charles C:. Thonias Publishers. Sauer, N. 1984. 'Manner of death: skeletal evidence of blunt and sharp instrument wounds', in Ku~kstra. J . and Rntlibun, T . (eds) Hcitnan Identif~cation: Case Studies In ForensicAt~tl~ropolog?', Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, pp. 176-1 84. S n ~ ~ eN. r , 1992. 'Forensic anthropology and the concept of race: if races don't exist, why are torensic anthropologists so good a t identifying them?', Social Sc~enc-ea n d Med~c-it7e34:2, 107-1 11. Scheuer, I.. and Bl,lck, S. 2000. L>el,clopn~cntalJul~cnile Ostcology. San Diego: Academic I'ress. Simmons, T., , J , i n t ~R., , and Bass, W . M . 1990. 'Stature estimation from fragmentary femora: a revision o t tlie Stcele neth hod', J o ~ ~ r t of ~ aForet~sic. l Scicv~ces35:3, 628-636. S ~ ~ n m o nT., s , Tuco, V., Kesetov~c,R. and CihlarL, Z. 1999. 'Evaluating age estimation in a Bosnia torens~cp o p ~ ~ l a t ~ o"Age-at-Stage" n: via Probit Analysis', paper presented a t the American Academy o t Forensic Sciences. February, Orlando. Sledig. P.S. and Ousley, S. 1991. 'Analysis of six Vietnamese trophy skulls',Jo~irr~al of ForensicSiiei~c-czs,36: 2, ,520-30. Smith, O.C., Berryman, H., and Lahren, C. 1987. 'Cranial fracture patterns and estimate o t direction from low veloc~t! gunshot wounds', Journal of Forens~cSciences 3 2 5 , 1416-1421. Steele. G . D. 1970. 'Estiniation o t stature from fragments of long limb bones', in Stewart, T.D. (ed.), Persotltrl Idr'i~trficat~ot~ 111 Mass Disasters, Washington, DC: National Museum of Natur;ll tlistor!, pp. 85-97. Stover, E. and Ryan, hZ. 700 1. 'Breliking bread with the dead', Society for Historic-a1Arc-haeology 3.5: I, 7-25. Trotter, M . and Gleser, G. 1952. 'Estimation of stature from long bones of American whites a n d negroes'. An~er~c-izi~ lourilal of Physiiul Anthropology 10, 463-5 14. Trotter, b1. and Gleser. C;.C:. 1958. 'A re-evaluation of estimation based o n measurements of stature taken during l ~ t eand long bones after death', Atneric-at1 ]ournu1 of Physic-a1 i \ t r t l ~ r o / ~ ~ l o16, g y 79-12.3. LJbelnker, I). H . 1987. 'Est~niatingage of death from immature human skeletons: a n overview', /oz1ri7~1l of Forensic S ~ r e t ~ e 32.5, es 1254-1263. IIbela ker, 1). H . and Jacobs, (1. 199.5. 'Identification of orthopedic device manufact~~rcr',Jourt~ul of For~ilsicSc.iet~c-es40:2, 168-170. White, T . 1). 2000. Hziitli~i~ O s t ~ o l o ~ q 211d y , edn. San 1)iego: Acadeni~cI'ress.