4th International Symposium on Particle Image Velocimetry PIV’01 Paper 1025

advertisement

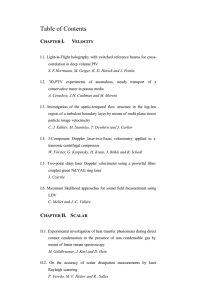

4th International Symposium on Particle Image Velocimetry Göttingen, Germany, September 17-19, 2001 PIV’01 Paper 1025 Modification of the Local Field Correction PIV technique to allow its implementation by means of simple algorithms. P. A. Rodríguez, A. Lecuona and J. Nogueira Abstract Presented in 1997, local field correction particle image velocimetry (LFCPIV) is the only correlation PIV method able to resolve flow structures smaller than the interrogation window. It presents advantages when compared with conventional systems and thus offers an alternative in the field of super-resolution methods. Improvements of the initial version are likely to promote its application even further. The issues defining some of these improvements were already indicated in the paper that introduced originally the LFCPIV, but were not developed at that time. This work presents refinements and also simplifications of the technique, so it can be applied using only current algorithms of advanced correlation PIV systems. Furthermore, these refinements reduce the measurement error and enlarge the application range of the LFCPIV. In particular, the application of the system is no longer constrained to images with mean distance between particles larger than 4 pixels. An analysis of the performance of the system is offered. This includes examples where the ability to cope with gradients in velocity and gradients in seeding density is highlighted. 1 Introduction PIV has been established as an important experimental tool for research as well as for development works in industry. Nevertheless, in many cases there is still a gap between the information contained in the images and what is extracted from them by current PIV systems. Recently, much of the effort of development on the technique has been focused on the extraction of as much information as possible from the images, being an example of this the super resolution or high resolution systems. On the other hand, the development of robust algorithms able to cope with specially difficult situations (i. e. large velocity gradients, seeding inhomogeneities, presence of boundaries, etc.) has been identified as a priority in research. Local Field Correction PIV (LFCPIV) (Nogueira, Lecuona and Rodríguez, 1999) is a clear alternative in both fields, at the cost of larger computing time than normal systems. The extra numerical work comes from the iterative character of the system and the conservative character of the progression towards better measurements, in order to avoid instabilities. The research performed since that former work, allows now for simplification of the technique and substantial improvements in performance. In this work refinements in respect to the previous version will be presented. 2 Basic procedure of LFCPIV The basic procedure of LFCPIV consist in an iterative method in which large interrogation windows are fixed in size and location. After each iteration the particle image is redefined through compensation of the particle pattern deformation caused by the velocity gradients in the displacement field. This means reducing displacements as well as the distortions of the particle pattern at the subpixel level. Both operations are jointly carried out using the displacement field from the previous evaluation. The theoretical end of this process is reached when both images fully coincide, thus yielding the highest possible correlation coefficient. The concept of obtaining high spatial resolution with large interrogation windows may seem initially contrary to understanding, because of that, this concept will be clarified along this section. P. A. Rodríguez, A. Lecuona, J. Nogueira, . Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Madrid, Spain Correspondence to: Prof. Antonio Lecuona, Departamento de Ingeniería Mecánica. Universidad Carlos III de Madrid C/ Butarque 15, 28911, Leganés. Madrid, Spain, E-mail: lecuona@ing.uc3m.es 1 PIV’01 Paper 1025 The idea of relocating the information of the original image in order to optimize the identification of the PIV correlation peak is not new. Keane and Adrian (1993) already proposed a discrete pixel offset between the pair of interrogation windows. The correction of the particle pattern deformation was implemented by Huang et al (1993) and Jambunathan et al (1995). Both reported instabilities in the iterations and, to avoid them, were forced to use a low-pass filter and/or to reduce the number of iterations to only a few. It was not until Nogueira (1997) and Nogueira, Lecuona and Rodriguez (1999) that the source of the instability was identified. These last works also introduced the way to avoid it without losing the inherently high spatial frequency resolution of the method. A detailed description can be found in the mentioned works and some insight in Lecuona, Nogueira and Rodriguez (2001) in this conference proceedings. The authors affirm that the use of a proprietary weighting in the interrogation window prevents the instability of the system. The recommended weighting function is as follows: ξ υ 2 ( ξ ,η ) = 9 4 F 2 −4 η ξ + 1 4 F F 2 −4 η + 1 F (1) Where ξ and η are coordinates with origin at the center of the interrogation window and F is the length of its side. The resulting expression for the calculation of the correlation coefficients is: F/2 Clm = ∑υ( ξ ,η ) f (ξ ,η ) ⋅ υ( ξ ,η )g( ξ + l ,η + m ) ξ ,η = −F / 2 F/2 F/2 ξ ,η = −F / 2 ξ ,η = −F / 2 (2) ∑υ 2( ξ ,η ) f 2(ξ ,η ) ∑υ 2(ξ ,η )g 2( ξ + l ,η + m ) Here f and g are the gray values of the two images to correlate, a and b respectively. l and m are the displacement associated to each calculation of the correlation coefficient. This way the frequency response of the PIV correlation is modified, allowing for a convergent iterative compensation of the particle pattern deformation as figure 1 diagrams try to visually describe. The detailed procedure is commented in section 3. Correlation Image a* Image a Correlation + Previous measurements Compensation of the particle pattern deformaton Image b* Image a* Image b Compensation of the particle pattern deformaton after several iterations (15 in this case) Image b* Fig. 1. Sketch of the LFCPIV iterative procedure. Black dots represent particle images in negative, grid-like distributed in order to show the particle pattern deformation. No error would yield a perfect cross ruled particle pattern after processing. Gray grid is for reference only, showing a rotation in the middle of the image and a shear at the borders after the compensation. Framed images represent actual measured displacement fields. Long horizontal arrows represent LFCPIV processing after 1, 2 and 15 iterations. Grid spacing is 16 pixels. As an example of quantitative performance, the particle pattern depicted in images a and b inside figure 1 was used. The initial data is selected corresponding to a Burgers vortex of 50 pixels radius and 6 pixels maximum 2 PIV’01 Paper 1025 displacement. The interrogation grid node spacing, ∆, was set to 16 pixels. Even in a simple case, like this one, with not very small spatial wavelengths in the displacement field the iterative procedure is worth it, as can be concluded from the following results. A first pass with F = 64 and weighted interrogation windows gives a measurement with relative errors > 13 % and absolute error > 0.8 pixels in some places. After 15 iterations, the relative error has been reduced to < 4 % and absolute error < 0.25 pixels. Being these last figures comparable with the unavoidable one related to the assumption of rectilinear displacement in the time between PIV images. As an example of the presence of instabilities when no weighting is applied, the same iterations were performed. Again, the same simple example is used to illustrate the point. Figure 2 presents the evolution of such a system. The quantitative results along the iterations follow. In the first measurement the relative error is > 64% in some places and the absolute error reaches 1.2 pixels. After 15 measurements, the divergence carries relative errors > 100% and absolute error to > 2.6 pixels in some places. Correlation Correlation + Previous measurements Image a* Image a Compensation of the particle pattern deformaton Image b* Image a* Image b Compensation of the particle pattern deformaton after several iterations (15 in this case) Image b* Fig. 2. Sketch of the LFCPIV iterative procedure without weighting function. Instability developement can be clearly distinguished. More details in figure 1 caption. It can be concluded that the application of the weighting function avoids instability, allowing for the iterative correction of the particle pattern. Unfortunately, it induces a small but accumulative erroneous slip in the measurements (Nogueira, Lecuona and Rodriguez, 1999). This slip is larger with smaller windows, making inadvisable its use for windows smaller than 32 pixels. Up to now, no way to deal with this slip is known by the authors, except applying some control on the iterative procedure in order to limit its contribution. This will be commented in the following section. 3 Refinement of the original LFCPIV method In this section, the refinement applied to the previous version of LFCPIV are described. 3.1 Initial considerations The starting point of any cross-correlation PIV system is a pair of images of the particle pattern, a and b, separated by a known time interval. Cross correlation of the corresponding interrogation windows, at the measurement nodes, approximates the displacement field of the particles from one image to the other. The next action in any iterative system is to use the information of this measurement to adapt the system in order to obtain a better one. In particular, in a system with compensation of the particle pattern deformation, a new couple of images a* and b* can be obtained, deforming and shifting a and b with the information of the approximate displacement field like is depicted in figure 1. This reduces the relative distortion, thus increasing the signal to noise ratio. Consequently, further analysis by cross correlating a* and b* yields new information allowing to reduce the error of the approximated displacement field. This provides image corrections to a and b that allows the calculation of 3 PIV’01 Paper 1025 successive images a* and b* to feed the iterative cycle. Details on the image processing can be found in Jambunathan et al (1995) and Nogueira, Lecuona and Rodríguez (1999). To be able to iterate without instability due to the effect depicted in figure 2, a weighting function like the one in expression (1) has to be used. The slip introduced by this weighting function accumulates through the iterations and starts to be significant at about 15 to 20 iterations. To avoid this error, an algorithm was designed in the birth of LFCPIV. The price to pay for was a reduction of the field of application of the system to images with average distance between particles δ > 4 pixels. Many PIV images are obtained in industrial and research wind tunnels, with a heavily seeded flow and with a strong need for high resolution. These images present small distances between particles and, actually, this means a better use of the limited CCD sensor resolution. This leads to the search for new solutions in order to deal with the error introduced by the weighting function. Here a new one without reduction of the field of application is proposed. Even more, the results obtained with this refinement reduce the uncertainty of the measurement, particularly at high spatial frequencies. 3.2 New approach to reduce the error introduced by the weighting function Observation of the measurement slip due to the weighting function leads to the conclusion that it is generally small, due to statistical cancellation in the interrogation window. This means that the nodes affected by significant slip are scarce. Consequently, a solution is to refuse correcting in the ongoing iteration the measured displacement in the few nodes with significant slip. This way, the evolution of these nodes to a worse measurement instead of a better one is avoided. This is the objective of the system here proposed. The detection of significant slip is performed in an approximate way, but the results obtained demonstrate that it produces a significant improvement. The nodes frozen in a certain iteration are those that show a slip large enough to be detected. The detection is based on the increase or decrease of the local correlation coefficient after each compensation of the particle pattern deformation. Several sources of noise mask the detection of slip. The main one is the influence of neighbor nodes on the change of the local correlation coefficient. A specific procedure was designed to deal with this phenomenon, which is described in detail in what follows. 3.3 Main algorithm of the refined system A detailed description of the refined system is specified through the following steps: 1. Calculation of local coefficients: The value of the local correlation coefficient C00 in a window with F = 2∆ is calculated for each grid node without weighting. This value will be used later to search for slip in the displacement values. This window corresponds to the region of influence of each grid node. 2. Initial processing of the images: This step is carried out as in a usual cross-correlation PIV process. The image is divided in overlapping windows (usually larger than the ones in the previous step) and these are cross-correlated to find the displacement peaks. The only difference with usual PIV is that the weighting function of expression (1) is applied. The resulting expression for the cross-correlation coefficients, Clm, has already been specified in expression (2). 3. Compensation of the particle pattern deformation: Correcting the particle pattern deformation gives images a* and b*. In the system here presented, the interpolation applied to obtain the gray levels is biparabolic, using the velocity grid nodes close to each pixel. The algorithm used do not present discontinuities between pixels. 4. Recalculation of local coefficients: The local correlation coefficients are obtained windowing with F = 2∆, images a* and b*. These values are compared to the ones obtained in step 1. A lower value may mean detection of a significant slip or simply contamination by neighbor slips. In consequence, out of the coefficients that worsen, only those surrounded by at least other 5 that also worsen, out of the 8 closest neighbors, are considered to contain significant slip. The evolution of the nodes with significant slip is avoided during this cycle. 5. Validation and interpolation of displacements to avoid intermediate false measurements: This step avoids obvious outliers in intermediate cycles, when signal to noise ratio is still not high enough. Any proven validation and interpolation algorithm would be useful. In particular, the ones applied here are those from Nogueira, Lecuona and Rodríguez (1997). 6. Compensation of the particle pattern deformation: With the approximation to the particle pattern displacement so far obtained, a new pair of images, a* and b*, are obtained again from a and b. The local coefficients between a* and b* are stored, like in step 1. 7. Further processing on the images a* and b*: These two images are fed to step 2. The measurement obtained is a correction to the previously estimated displacement field. Adding this correction, a new approximation to the particle pattern deformation is obtained. This is supplied to step 3, defining the iterative loop. 4 PIV’01 Paper 1025 3.4 Control loops of the main algorithm The evolution of the error in these iterations is qualitatively similar to that of its former version (decreasing fast at the beginning to increase slowly after a minimum, owing to the mentioned slip error). To decide when to stop the iterations, an improved method has been implemented. It is based on the evolution of the local coefficients (obtained in step 1 of the main algorithm) from one iteration to the following. A description of the control loops follows: Low pass initial iterations: The first steps in the measurement are characterized by large errors, caused by the correlation peak distortions. These come from the initial large gradients in the images, for the deformations in the particle pattern have been scarcely compensated. It has been observed that this initial error can be reduced through a local smoothing of the displacement field measured in the first steps. This initial stage is carried out by applying the main algorithm described in section 3.3 with F = 64 for several iterations, applying a moving average of 3 by 3 grid nodes after each iteration. This stage extends until the local coefficients that worsen from one iteration to the following are more than half of the ones that improve. This indicates that this stage benefits are being counterbalanced by the drawbacks. After that, the same procedure is repeated with F = 32 in order to increase the accuracy of the results, but still the smoothing rejects the initial errors. This low-pass initial stage has proven to reduce ≈ 15% the error related to high frequencies in the end result of the whole system. Extraction of small features: Once a first stage has been completed, the procedure is applied without any smoothing, therefore allowing for the full spatial resolution. This is performed through two modes of operation: - Mode 1: this represents a normal iterative PIV operation. All the nodes are allowed to evolve. When the worsening nodes are more than half of the improving ones, the system changes to mode 2. The rationale behind this is to detect that a large enough number of nodes have already converged. - Mode 2: only the nodes with local correlation coefficient under the average value, at the time of mode change, are allowed to evolve. When the worsening nodes are more than the improving ones the system changes to mode 1. This mode complements mode 1 as it freezes the already converged nodes, allowing the more slowly evolving ones to proceed. If no further iteration is performed in mode 1 or 2, the system stops. The resulting method, so far described, only requires two types of basic algorithms: interpolation of gray levels and correlation calculation. Algorithms on validation and interpolation of vectors are a valuable option, and almost essential for intermediate steps, when either the noise or the velocity gradients are large. A detail that further increases the accuracy of the system and that will be applied in this paper is to symmetrize the correlation algorithm. An alternative formulation to expression (2) can be obtained swapping f and g. The resulting displacement can be averaged with the one from expression (2). The performance shows an error reduction of ~ 3%. The price to pay is to double the computing time. It is also of interest to note that when the displacements to measure are smaller than 0.5 pixels (typically after the 3rd iteration or so) only the central correlation coefficient plus its four closest neighbors have to be calculated as the peak is now very narrow. For this case a direct correlation is more efficient than an FFT algorithm. Nevertheless, application of the system for high resolution typically on dense images requires more than 100 iterations with ∆ on the order of 4 pixels, making this a considerable computational load. It requires, like its previous version, a time in the order of 10+(n-5)/5 times what is required for a conventional system (being n > 5 the number of iterations). 4 Evaluation on Synthetic images The basic performance evaluation of this method has been based on 1D single frequency displacement fields, implemented in two sets of images containing: 1 Due to the relation between the present work and Nogueira, Lecuona and Rodriguez (1999), and to allow direct comparison, one set of synthetic images have been the ones from that work. In these images, the mean distance between particle images is δ = 4.5 pixels (i.e. 4/(π·δ2) ~ 0.06 ppp (particles per pixel)). The mean diameter of particle images is d = 4 pixels. Their shape is Gaussian, being the diameter d associated to e-2 times the maximum gray value. Where particles overlap, the corresponding intensities are added. 5% of particles have no second image to correlate, simulating out of plane displacement. The results on this set of images are plotted in figure 3a. 2 It is also common to isolate different sources of error. To observe the performance of the system in respect to the wavelength exclusively, a different set of images was used. They correspond to good conditions for high resolution. In them, the mean distance between particle images is δ = 2 pixels (i.e. 4/(π·δ2) ~ 0.3 ppp (particles per pixel)). The mean diameter of particle images is d = 2 pixels. Their shape is Gaussian, being the diameter associated to e-2 times the maximum gray value. Where particles overlap, the corresponding intensities are added. 5 PIV’01 Paper 1025 No out of plane displacement was considered. The results on this set of images are plotted in figure 3b. The application to these images highlights that the restriction of the previous version of application to images with δ > 4 pixels has been removed. Displacement field: s = 2sin(2πx /λ x ) (pixels) 0.7 Former LFCPIV 0.6 rms(e )/rms(s ) rms(e )/rms(s ) 0.6 Displacement field: s = 2sin(2πx /λ x ) (pixels) 0.7 0.5 0.5 0.4 0.4 Refined LFCPIV 0.3 Refined LFCPIV 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.1 0 0 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 λ x (pixels); (δ =4.5 pixels). 55 60 20 25 30 35 40 45 λ x (pixels); (δ =2 pixels). 50 55 60 Figure 3. a) Performance of LFCPIV systems for the indicated displacement fields in the presence of usual noise and large distance between particles. b) Performance of LFCPIV for the indicated displacement in good conditions for high resolution. One last observation is that in the LFCPIV system presented here, even in the case of losing the information of a displacement feature (flow structure) that could be resolved with the grid spacing, the low value of the local coefficient defined in the previous section would inform about it. With this information, the time between pulses could be reduced and the feature would be more easily tracked. Therefore, the LFCPIV system shows a high robustness besides a high accuracy, beyond other current high-resolution techniques. 5 Application to real images As example of performance of the refined LFC system over real PIV images the images already used in Lecuona et al. (1999) have been selected. This way, some comparison with the previous version of LFCPIV is possible. The images correspond to the analysis of a lean premixed LOWNOX gas turbine combustion chamber (Lázaro et al. 1998). The setup has two parallel premixing tubes (main and pilot). The main tube has an outlet diameter of 43 mm and the pilot has a diameter of 29 mm. They both discharge upwards to the transparent combustion chamber and the main is at one side and 40 mm above the pilot. The swirl number of both combustors is 0.51. The area expansion of the combustion chamber caused vortex breakdown and this generates a main recirculation bubble where there is an important turbulence, higher that 50% in intensity. The plane where the PIV measurements are taken corresponds to a cross-cut of both combustors though their axis. In this example, the main combustor was burning and the pilot was off, thus giving a large difference in seeding density of the flow (due to the volume expansion in the flame). Figure 4a depicts a close-up detail of the mixing region between these two flows. This figure is 10 mm above the main burner exit. The seeding particles are Alumina powder of ∼4 µm particle size. The magnification results in 4.2 pixels/mm and the time between laser pulses is 10 µs. Thus, a 2 pixels displacement, like the one depicted in the scales of figure 4, corresponds to 48 m/s. Besides showing the ability of LFCPIV to describe structures smaller than the interrogation window, this example shows its ability to cope with high seeding inhomogeneities and high dispersion in the brightness of the particles. Figure 4b depicts the measurements obtained with a PIV system with 32 by 32 pixels interrogation window. Smaller windows could not be used due to the low signal to noise ratio. Figure 4c depicts the measurements obtained with the former version of LFCPIV, while figure 4d shows the measurement obtained with the refined version. All the measurements were performed with ∆ = 4 pixels. It is aparent from the results that the refined system is able to resolve smaller flow structures, although not definitive conclusions can be drwn from this dificult image. To further appreciate the differences, figure 5 shows the vorticity field in both cases. 6 PIV’01 Paper 1025 = 2 pixels a b = 2 pixels = 2 pixels c d Fig 4. a) Image of the flow field, showing seeding density differences. b) Velocity field calculated using a usual PIV system. b) Velocity field calculated using the previous version of LFCPIV. c) refined LFCPIV. Vorticity (1/∆t) -0.45--0.35 -0.35--0.25 -0.25--0.15 -0.15--0.05 Vorticity (1/∆t) -0.05-0.05 0.05-0.15 0.15-0.25 0.25-0.35 -0.45--0.35 c -0.35--0.25 -0.25--0.15 -0.15--0.05 -0.05-0.05 0.05-0.15 0.15-0.25 0.25-0.35 d Fig 5. a) Vorticity plot from flowfield in figure 4c b)Vorticity plot from flowfield in figure 4d. ∆t makes reference to the time between images. 6 Conclusions A refined LFCPIV method that only uses current algorithms of any advanced 2D PIV system (interpolation of the image and correlation calculation) has been developed and its metrological quality tested. The new system presents some advantages in respect to its previous version. It offers no restriction on mean distance between particles. And it shows a reduced measurement uncertainty in respect to its predecessor. The result is a robust high-resolution system able to cope with large seeding density and velocity gradients. The main drawback in LFCPIV comes from the slip introduced by the unavoidable weighting function. A way for further improvements would be to develop methods to cope with this difficulty. The computing cost of the refined method is similar to the previous version. Nevertheless, it should be underpinned that the computing time is related to the number of iterations. These can be reduced at the expense of accuracy, if necessary. In general, the system is conceived as an off line process that gives more information from the images. The images could be analyzed on line during acquisition with any usual system. The combination of these two capabilities in LFCPIV (i. e. to cope with large velocity gradients and to resolve small structures in the flow) results in a very robust high-resolution technique. 7 PIV’01 Paper 1025 Acknowledgements This work has been partially funded by the Spanish Research Agency grant DGICYT TAP96-1808-CE, PB95-0150CO2-02 and under the EUROPIV 2 project (A JOINT PROGRAM TO IMPROVE PIV PERFORMANCE FOR INDUSTRY AND RESEARCH) is a collaboration between LML URA CNRS 1441, DASSAULT AVIATION, DASA, ITAP, CIRA, DLR, ISL, NLR, ONERA, DNW and the universities of Delft, Madrid (Carlos III), Oldenburg, Rome, Rouen (CORIA URA CNRS 230), St Etienne (TSI URA CNRS 842), Zaragoza. The project is managed by LML URA CNRS 1441 and is funded by the CEC under the IMT initiative (CONTRACT N°: GRD1-1999-10835) References Huang H T; Fiedler H E; Wang J J (1993b) Limitation and Improvement of PIV (Part II: Particle image distortion, a novel technique). Exp. Fluids. 15: 263-273. Jambunathan K; Ju X Y; Dobbins B N; Ashforth-Frost S (1995) An improved cross correlation technique for particle image velocimetry. Meas. Sci. Technol. 6: 507-514. Keane R D; Adrian R J (1993) Theory of cross-correlation of PIV images. Nieuwstadt FTM (ed). Flow Visualization and image Analysis. Dordecht: Kluwer Academic, pp 1-25. Lázaro B; Gozalez E; Alfaro J; Rodriguez P A; Lecuona A (1998) Turbulent Structure of Generic LPP Gas Turbine Combustors. Proceedings of the Research and Technology Organization of NATO Meeting, Lisbon, Portugal Oct. 1998. RTO-MP-14: 25-1 to 25-11. Lecuona A; Nogueira J; Rodríguez PA; Ruiz-Rivas U; Alfaro J (1999) Local Field Correction PIV: a superesolution technique. 3rd Int. Workshop. on PIV’99. University of California Santa Barbara. USA (late paper). Nogueira J (1997) Contribuciones a la técnica de velocimetría por imagen de partículas (PIV). Ph. D. Thesis. E. T. S. I. Aeronáuticos, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Spain. Nogueira J, Lecuona A and Rodríguez P A (1997) Data validation, false vectors correction and derived magnitudes calculation on PIV data. Meas. Sci. Technol. 8: 1493-1501. Nogueira J, Lecuona A and Rodríguez PA (1999) Local Field Correction PIV: On the increase of accuracy of digital PIV systems. Exp. Fluids 27/2: 107-116. 8