ARTICLE CHARITABLE CONTRIBUTIONS OF PROPERTY: A BROKEN SYSTEM REIMAGINED R

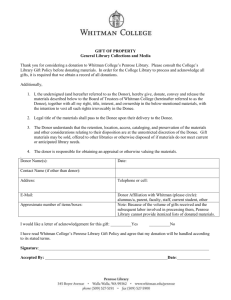

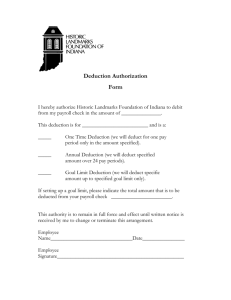

advertisement