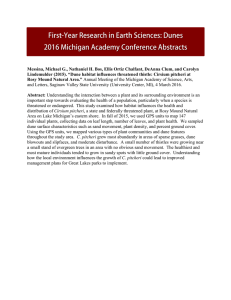

Investigation of the Syndicate Park Dune Area

advertisement