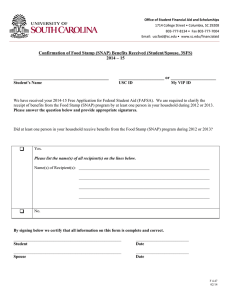

Enhancing Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Certification: SNAP Modernization Efforts Interim Report

advertisement