Evidence Matters

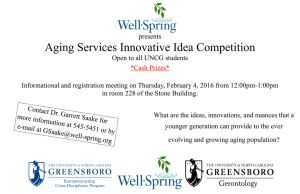

advertisement