Community-Higher Education Partnerships: Community Perspectives Annotated Bibliography Compiled by:

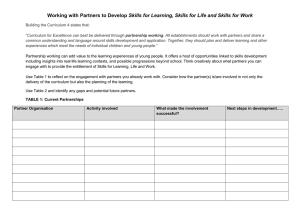

advertisement