1 I’m The Impact of Personal Pronoun Use in Customer-Firm Interactions

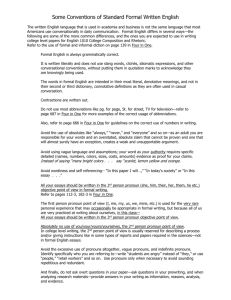

advertisement