Children on the Brink 2004 a Framework for Action July 2004

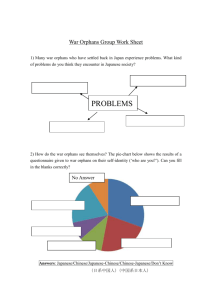

advertisement